Some genetic mutations linked to leukemia aren’t very helpful in guiding treatment decisions for patients. A new study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggests a set of clinical signs that, when combined with genetic testing, can help doctors decide when to start more aggressive treatment.

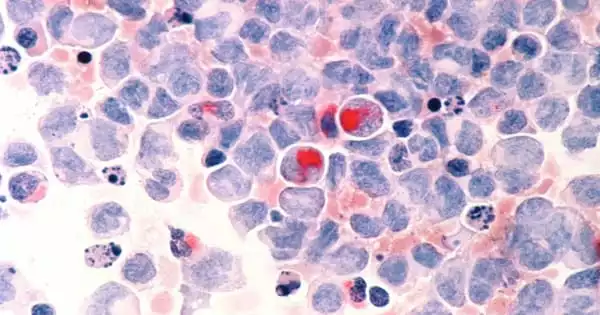

Studies of leukemia, or cancer of the blood and blood-forming cells, have revealed changes in genes that are associated with the disease, and these genetic changes can be passed down from generation to generation. In some cases, these changes provide doctors with a way to predict disease risk. Others are unsure what the consequences will be. Even when the link between a particular genetic red flag and disease is strong, it may be difficult to pinpoint when serious stages of the disease may begin.

“This is extremely variable. In a family with a common mutation, a grandfather may not exhibit symptoms until leukemia emerges suddenly” Alexandra Soukup, a cancer researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “In contrast, one of their grandchildren with the same genetic alteration may develop serious symptoms as early as age seven, such as lymphedema (severe swelling in the arms and legs) or cytopenia (low blood cell levels), which can lead to life-threatening infections. We want to know what environmental and genetic factors cause the disease to manifest itself.”

Our mouse model provides a unique system for discovering what may trigger severe disease presentations in humans, and we can use it to develop strategies to counteract or eliminate the triggering. Such strategies would be beneficial to patients, and we would like to implement them.

Alexandra Soukup

Clinicians treating patients with leukemia-causing genetic mutations would like to know as well, because their options range from non-invasive monitoring or drugs to invasive procedures such as radiation, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplants.

“Right now, a bone marrow transplant is the gold standard for treatment,” Soukup says. “However, these occur when there is already a relatively severe disease presence, elderly patients are frequently ineligible for transplants, and transplants can result in life-threatening reactions.”

The complications of leukemia, which causes the bone marrow to produce insufficient or abnormal blood cells, can be triggered by exposure to a pathogen or toxin, requiring the body to increase production of new blood cells.

Soukup, a UW-Madison Cell & Regenerative Biology professor, and Emery Bresnick, director of the Wisconsin Blood Cancer Research Institute, and colleagues exposed mice with a genetic mutation associated with leukemia to “triggers” that created a model for bone marrow failure. This frequently occurs before the onset of leukemia. The researchers’ findings were recently published in the journal Science Advances.

“These mutations have little to no effect on steady-state blood cell production, and the mice containing the mutation may appear normal most of the time,” says Soukup, a researcher in Bresnick’s lab. “It’s only when you subject them to other stresses that severe defects appear.”

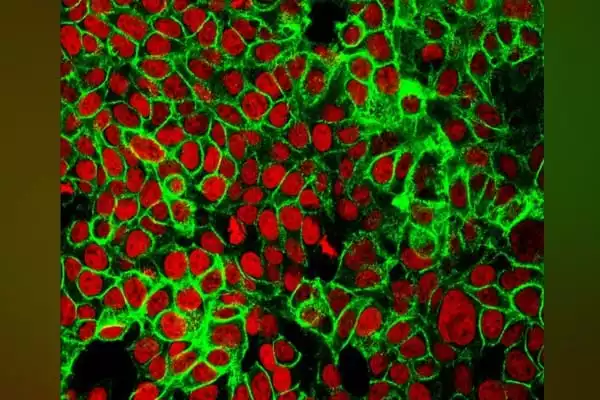

The mice were stressed in one of three ways, to mimic in a short period of time the types of environmental and immunological challenges that humans may face over time: with a common chemotherapy drug, a component in bacterial cell walls that causes inflammation, or a drug used to boost stem cell division before human transplants. They were curious to see how the mice’s bone marrow would react. Stem cells in healthy marrow should divide and mature into new blood cell producers to pick up the slack in times of need.

“In all of our cases, the stem cells appeared relatively normal,” Soukup says, “but they failed to respond or were extremely impaired in their response to expand.” “With the chemotherapeutic, you’d expect stem cells to proliferate and blood cells to regenerate, replacing what the chemotherapy had destroyed. My mutant animals were unable to respond.”

The animals died of bone marrow failure in the absence of stem cell expansion. By investigating how the mutant mice responded to these stressors, the researchers hope to gain a better understanding of the types of human health issues, such as recurring infections, that can lead to life-threatening leukemia.

“Our mouse model provides a unique system for discovering what may trigger severe disease presentations in humans, and we can use it to develop strategies to counteract or eliminate the triggering. Such strategies would be beneficial to patients, and we would like to implement them” Soukup explains. “If you’ve already presented with X, Y, and Z, and you’ve been exposed to these risk factors, this may allow medical decisions to avoid the crisis scenario in which severe disease emerges rapidly.”