An international team of researchers collected genetic evidence from families of genetic skin diseases, amassing insights over three decades. This genetic research helped to classify the guilty mutants for unusual skin conditions, including bullosa epidermolysis (EB). EB results in incredibly delicate skin are noticeable in affected newborns and can lead to blissful and poorly healed wounds from even light contact. Infancy characteristics include very soft skin, thickened palms of the hands and soles of the knees, and hair loss, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Our skin tells us when we’ve spent too much time in the sun or when the dry air of winter has sucked away too much moisture. Now Jefferson researchers find that the skin can also foretell issues unrelated to the protective barrier.

This team of researchers led by Jouni Uitto, MD, Ph.D., Professor of Dermatology and Cutaneous Biology, confirmed that mutations in a gene thought to underlie unusual skin conditions often contribute to severe heart disease. The results are the latest example from Dr. Uitto’s laboratory to prove that, when combined with genetic research, the skin will help identify potential medical problems.

“By looking into the skin of newborns, we can predict the development of a devastating heart disease later in life,” Dr. Uitto says. “This is predictive personalized medicine at its best.”

Dr. Uitto has been hunting mutations worldwide in families of inherited skin defects for three decades. For the past five years, he and his colleagues have studied mutations in around 1,800 families around the world, looking for genetic culprits underlying skin disorders such as bullosa epidermolysis (EB). EB is a dangerous illness that makes the skin very brittle. Patients with EB have the potential to develop blisters and poorly healed wounds with the slightest touch.

A closer look at heart disease risk

In the latest publication, the co-authors Hassan Vahidnezhad and Leila Youssefian, and a small group of researchers looked at the DNA of more than 360 EB patients from around the world. In specific, DNA obtained from blood samples was examined for sequence variants in a group of 21 genes known to harbor mutations that cause EB. The study found that two patients had precisely the same mutation in a gene known as JUP.

The patients have displayed the same signs in early childhood, including very fragile skin, thickened skin on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and hair loss that spread to the eyebrows and eyelashes. But now one patient was a 2.5-year-old child that just showed skin abnormalities, and the other was a 22-year-old woman who already had a cardiac disease called arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) (ARVC).

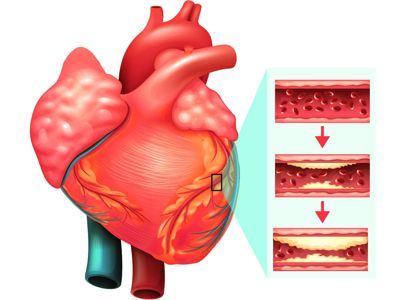

“This is a serious disease that can require a heart transplant if the damage is too severe because of heart failure and life-threatening fast heart rhythms,” says Reginald Ho, MD, a cardiologist in the department of medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, who co-authored the study.

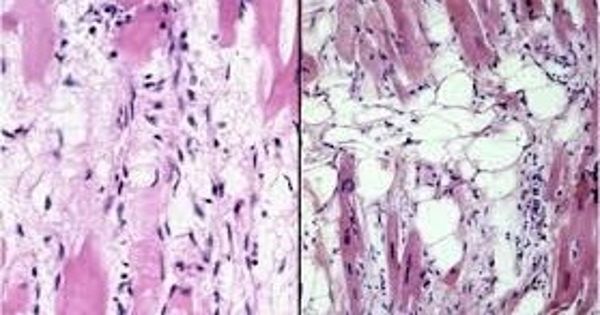

In ARVC, stiff, fibrous tissue displaces healthy heart muscles over time. As a result, the heart experiences irregular rhythms and becomes sluggish. Patients with ARVC are vulnerable to heart disease and premature cardiac death. Indeed, ARVC is blamed for as many as 20% of sudden heart deaths for those under the age of 30. Most need an implantable defibrillator to treat life-threatening arrhythmias. JUP mutations that cause EB may also contribute to the stiffness of the heart muscle and ARVC.

Although the young boy has not yet had heart complications, the genetic results indicate that he will experience them down the way. “This means that with mutation analysis, you can predict when looking at EB patients at birth, whether they will have this very severe heart condition later in life,” says Dr. Uitto. “These patients need to be monitored carefully for heart problems,” he says.

The results contribute to the series of insights that Dr. Uitto and colleagues have revealed in recent years in their quest for genes that underlie extreme skin conditions. For example, in 2019, researchers found that patients with skin conditions known as ichthyosis may experience liver complications that are significant enough to require a transplant later in life.

“We are looking to identify new genes behind skin diseases like EB and ichthyosis,” Dr. Uitto says. “By looking at patients’ symptoms and family history, we have uncovered something completely unexpected.”