The environmental impact of beef farming is a complex issue involving numerous factors such as feed type, management practices, and the overall lifecycle of the cattle. While grass-fed beef production has been linked to environmental benefits such as improved soil health and reduced reliance on grain crops, it does not always result in a lower carbon footprint when compared to conventional methods.

Beef operations that keep cattle on grass-based diets for their entire lives may have a higher overall carbon footprint than those that switch cattle to grain-based diets halfway through their lives. These findings were published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Daniel Blaustein-Rejto of the Breakthrough Institute in the United States and colleagues.

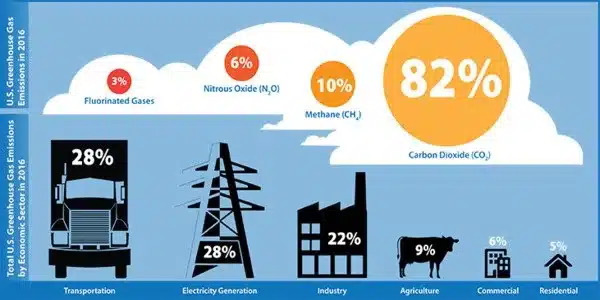

Cattle that have been fed grass their entire lives are considered “pasture finished,” whereas those that switch from grass to grain before slaughter are considered “grain finished.” According to previous research, pasture-finished beef operations have a higher carbon footprint than grain-finished operations. Most studies, however, have focused solely on the amount of greenhouse gases emitted directly by beef production, without taking into account other factors that may affect the overall carbon footprint.

Our research reveals that the carbon cost of land use accounts for the largest part of beef’s carbon footprint. Therefore, there is an even larger carbon cost than typically found to land-intensive beef operations, such as many grass-fed systems, even when taking into account potential carbon sequestration due to grazing.

Blaustein-Rejto

Blaustein-Rejto and colleagues calculated and compared the carbon footprints of 100 beef operations in 16 countries to gain a better understanding. In addition to direct greenhouse gas emissions, their calculations included soil carbon sequestration, which is the capture and long-term storage of atmospheric carbon in pasture soils, often in the form of dead plants and cattle waste. They also considered the carbon opportunity cost, or the carbon that would have been sequestered if the land had been used for native ecosystems rather than beef production.

Extensive statistical analysis showed that pasture-finished operations produce 20 percent more greenhouse gases than grain-finished operations – in line with prior studies. However, after incorporating soil carbon sequestration and carbon opportunity cost, the total carbon footprint of pasture-finished operations was 42 percent higher, likely due to its more intense usage of land.

Further investigation revealed that increasing land use intensity is strongly associated with a larger overall carbon footprint for beef operations. Carbon opportunity costs may contribute even more to an operation’s overall carbon footprint than direct greenhouse gas emissions, according to the calculations, when averaged across all operations in the study.

According to the researchers, their findings highlight the importance of including carbon opportunity costs in climate mitigation efforts. With pasture-finished beef often perceived as more premium, carbon footprint data may provide valuable additional information to aid consumer decision-making.

The authors add: “Our research reveals that the carbon cost of land use accounts for the largest part of beef’s carbon footprint. Therefore, there is an even larger carbon cost than typically found to land-intensive beef operations, such as many grass-fed systems, even when taking into account potential carbon sequestration due to grazing.”