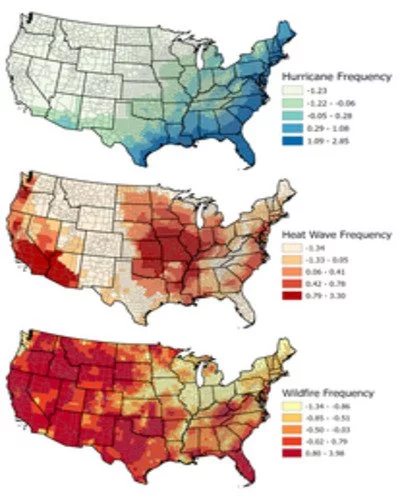

According to one of the greatest studies of U.S. migration and natural disasters, Americans are moving away from many of the U.S. counties most severely affected by hurricanes and heatwaves and toward deadly wildfires and warmer weather.

The ten-year nationwide survey indicates alarming public health trends, with Americans moving to areas with high summer temperatures and the risk of wildfires. These environmental risks now significantly harm people and property each year, and it is predicted that they will get worse due to climate change.

“These findings are concerning because people are moving into danger’s way – into regions with wildfires and rising temperatures, which are expected to become more extreme due to climate change,” said Mahalia Clark, lead author of the University of Vermont (UVM) study, noting that the study was inspired by the increasing number of headlines of record-breaking natural disasters.

The study, titled “Flocking to Fire,” was published by the journal Frontiers in Human Dynamics. It is the largest investigation yet into how natural disasters, climate change, and other factors impacted U.S. migration over the last decade (2010-2020). “Our goal was to understand how extreme weather is influencing migration as it becomes more severe as a result of climate change,” Clark explained.

The top U.S. migration destinations over the last decade were cities and suburbs in the Pacific Northwest, parts of the Southwest (in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Utah), Texas, Florida, and a large swath of the Southeast (from Nashville to Atlanta to Washington, D.C.) – locations that already face significant wildfire risks and relatively warm annual temperatures, the study shows. In contrast, people tended to move away from places in the Midwest, the Great Plains, and along the Mississippi River, including many counties hit hardest by hurricanes or frequent heatwaves, the researchers say.

We hope this study will increase people’s awareness of wildfire risk. When you’re looking for a place to live on Zillow or through real-estate agents, most don’t highlight that you’re looking at a fire-prone region, or a place where summer heat is expected to become extreme.

Clark

“These findings suggest that, for many Americans, the risks and dangers of living in hurricane zones may be beginning to outweigh the benefits of living there,” UVM co-author Gillian Galford said. The term “independent” refers to a person who does not work for the government.

Given how development can exacerbate risks in fire-prone areas, one implication of the study is that city planner may need to consider discouraging new development where fires are most likely or difficult to fight, according to the researchers. At minimum, policymakers must consider fire prevention in areas of high risk with large growth in human populations, and work to increase public awareness and preparedness.

“We hope this study will increase people’s awareness of wildfire risk,” said Clark, noting the study includes several maps highlighting the severity of national hazards across the country. “When you’re looking for a place to live on Zillow or through real estate agents, most don’t highlight that you’re looking at a fire-prone region or a place where summer heat is expected to become extreme. You have to do your research,” said Clark, noting the website Redfin recently added risk scores to listings.

Despite climate change’s underlying role in extreme weather events, the team was surprised by how little the obvious climate impacts of wildfire and heat seemed to impact migration. “If you look where people are going, these are some of the country’s warmest places – which are only expected to get hotter.”

“Most people still think of wildfires as a problem in the West, but wildfire now affects large swaths of the country – the Northwest down to the Southwest, but also parts of the Midwest and the Southeast like Appalachia and Florida,” said Clark, a researcher at UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment and Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources.

Aside from aversion to hurricanes and heatwaves, the study identified several other clear preferences – a mix of environmental, social, and economic factors – that have also contributed to U.S. migration decisions over the last decade.

The team’s analysis revealed a set of common qualities shared among the top migration destinations: warmer winters, proximity to water, moderate tree cover, moderate population density, better human development index (HDI) scores – plus wildfire risks. In contrast, for the counties people left, common traits included low employment, higher income inequality, and more summer humidity, heatwaves, and hurricanes.

Researchers note that Florida remained a top migration destination, despite a history of hurricanes and increasing wildfire. While people were less interested in hurricane-ravaged areas across the country, many people, particularly retirees, continued to flock to Florida, drawn by the warm climate, beaches, and other characteristics shared by top migration destinations. Although hurricanes are likely to influence people’s decisions, the study suggests that the benefits of Florida’s desirable amenities still outweigh the perceived risks of living there, according to the researchers.

“The decision to move is a complicated and personal decision that involves weighing dozens of factors,” said Clark. “Weighing all these factors, we see a general aversion to hurricane risk, but ultimately — as we see in Florida – it’s one factor in a person’s list of pros and cons, which can be outweighed by other preferences.”

For the study, researchers combined census data with data on natural disasters, weather, temperature, land cover, and demographic and socioeconomic factors. While the study includes data from the first year of the COVID pandemic, the researchers plan to delve deeper into the impacts of remote work, house prices, and the cost of living.

The study, “Flocking to Fire: How Climate and Natural Hazards Shape Human Migration Across the United States,” is the most comprehensive examination yet of how natural disasters and climate change have impacted migration in the United States over the last decade.

Warmer temperatures, as well as more frequent and severe extreme weather events, such as heat waves, hurricanes, wildfires, and floods, are expected as global climate change progresses. Every year, these events kill dozens of people and cause billions of dollars in damage.