William King Hale arrived in what is now Osage County, Oklahoma, about 1902, impoverished and forced to live in a tent. By the 1920s, he was so wealthy and powerful that everyone feared being on his bad side. He’d earned the moniker “King of the Osage Hills.”

He was convicted as the merciless mastermind behind the Osage Murders, a horrifying string of homicides that became the FBI’s first significant case.

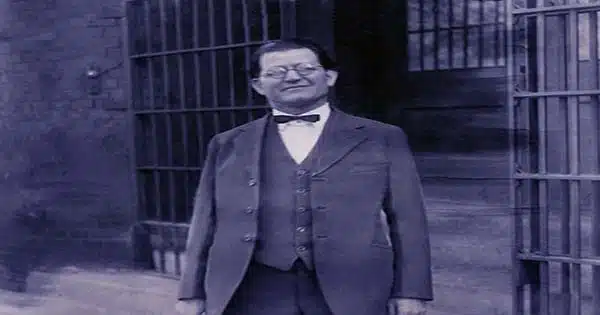

In a 1926 newspaper article, Hale was characterized as 5’7″ and 155 pounds, with “a beautiful body” and a “unusually enormous” chest. It went on to describe his walk as “erect and springy.” A later author noted his “thick glasses, which gave him a [deceptively] benign, friendly look.”

The discovery of oil on the Osage Nation’s grounds coincided with Hale’s climb from cowboy to king, making the Native American tribe the wealthiest people on the planet, per capita. Hale had no claim to the Osage riches because he was not a member of the tribe. But he knew how to get in on the action: he’d steal it.

One of Hale’s nephews had married an Osage woman, which may have been a happy accident or a cunning plan. In 1917, the year of their marriage, her annual income from the oil rights was $2,608.99, which is roughly $82,000 today. Not only that, but she stood to inherit her relatives’ properties and oil rights if they died before her.

Hale figured that could be arranged: Throughout a half-decade, at least nine people would die as a result of Hale’s murder spree—some shot, others poisoned, and three died in an explosion that demolished their home. Most were Osage, but some were white residents who either knew too much or were just in the way. According to some estimates, the death toll ranged from 24 to 60 or more. Many suspicious deaths went completely uninvestigated.

Too wealthy and astute to take the law into his own hands, Hale solicited the help of others and ensured he had excellent alibis. Even people who suspected his involvement assumed that his money and political ties would shield him from prosecution. Then, because to the perseverance of a few remaining tribal members, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI became interested in the case, and Hale’s fortunes altered.

For decades, Hale was mostly forgotten, until the 2017 publication of David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon, which director Martin Scorsese adapted into a 2023 film of the same name, starring Robert DeNiro as Hale.

Hale Began as a Texas Cowboy: William King Hale was born on Christmas Eve 1874 near Greenville, Texas, to what one old acquaintance described as a “large, respectable, and wealthy family.” Bill’s father was a farmer and rancher, and when he was 16, he wanted to leave home to become a cowboy. He spent the next few years traveling between Texas and Oklahoma Territory, purchasing and selling cattle, some of which he was accused of rustling. “He is the most energetic man I ever knew,” the same acquaintance said in a press interview in 1926. “He was never idle. Even when he crossed the street, he pretended to be on the lookout for something significant.”

Hale, now married to a young schoolteacher, moved to the Osage Hills in Northern Oklahoma in 1902, where he and his wife spent their first spring living in tents. He was $10,000 in debt (about $350,000 in 2023 dollars) due to unidentified financial setbacks. After several years of working for other ranchers, he formed a partnership with two local bankers and began leasing grazing land from the Osage. He’d eventually own leases on 45,000 acres and own another 5,000 acres completely. His other investments would include financial stakes in a bank, a general shop, and, perhaps most aptly, a funeral parlor.

But that was insufficient for the ambitious Hale. He recognized that the true wealth resided deep underneath the Osage grazing fields, not on them.

Hale Targeted Osage Oil Heiress, Mollie Burkhart: Oil was discovered beneath Osage lands as early as the 1890s, but it wasn’t until around 1907 that business took off. Members of the Osage tribe jointly controlled the oil rights and distributed the revenues evenly among themselves via “headrights.” According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, by 1926, the “average Osage family of a husband, wife, and three children” earned more than $65,000 per year (more than $1.1 million today).

Mollie Burkhart, a tribal member and the wife of Hale’s nephew Ernest Burkhart, was among those who benefited from the oil money gusher. According to other reports, Hale himself persuaded the young man to marry her.

Mollie’s family had a stunning series of misfortunes beginning in 1918. First, her younger sister Minnie, who was 27 and appeared to be in good health, died of a mysterious “wasting” sickness. Anna Brown, her sister, was murdered in May 1921. Lizzie Kyle, their mother, died in July, possibly from poisoning. In January 1923, Henry Roan, a relative, was killed in another shooting. Lizzie’s second daughter, Rita Smith, was killed along with her husband and housekeeper two months later when an explosion ripped through their home. Mollie and Ernest received all of their cash and oil rights.

Mollie believed she would be the next victim with good cause. That meant Ernest would get everything, putting it within easy reach of his uncle, William King Hale, who had excellent cover. Hale, a long-standing community member, had built a beneficent facade as a generous friend to the Osage.

FBI Agents Met a “Unbreakable Wall of Fear”: Tribal leaders petitioned the federal government to intervene in the spring of 1923. The Justice Department delegated the investigation to the newly formed Bureau of Investigation, as it was known at the time. Its investigation would last three years.

Agents encountered “an almost impenetrable wall of fear,” according to Don Whitehead in The FBI Story (1956). “People who were afraid to talk and witnesses who might have given information had long since disappeared.” Because Hale had long already brought them into cooperation, prominent area police, doctors, and others remained silent. Four undercover investigators were eventually able to crack the case, thanks in part to Ernest Burkhart’s cooperation.

A federal grand jury indicted Hale for the murder of Henry Roan in January 1926. Roan was killed on federal rather than tribal grounds, therefore the government has authority over the issue. Prosecutors claimed Hale’s motivation was a $25,000 life insurance policy he had taken out on the man’s life. The alleged triggerman, John Ramsey, described in the press as a “cowboy farmer,” was charged with the same offense.

The initial trial effort was thwarted owing to a legal snag. The second trial, which started in July, concluded with a deadlocked jury. The guys were retried in October, and by the end of the month, both had been convicted of first-degree murder.

Hale’s attorneys successfully challenged the conviction, which resulted in a fourth trial in January 1929. Hale was convicted once and for all this time. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Courtroom spectators remarked on Hale’s steely serenity during his several trials. “Should Hale be given a death penalty,” a reporter wrote in the summer of 1926, “some say he will help the executioner adjust the rope around his neck and will go to his death with the smile that seldom leaves his face.”

When Hale left the courthouse after hearing the guilty decision in October, he was “in a cheerful frame of mind,” according to the Associated Press, and his lawyers said he was still “jovial” the next morning.

When Hale testified three years later at his retrial in 1929, a reporter noticed “a voice that held no tremor and a demeanor that bore no apparent anxiety.” Another reporter noted that when the court clerk read the guilty verdict, “the defendant gave no sign of emotion.”

The Exiled ‘King’: John King Hale, a model prisoner, spent the better part of the following two decades in the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, or on the adjoining prison farm. His parole release in July 1947 surprised the Osage people, who thought he had been imprisoned indefinitely.

“In our minds, there is no doubt that Hale was the ringleader in the mass murder of our tribesmen,” remarked one prominent Osage member. “His good behavior in prison does not change the fact. I believe he should have been executed for his crimes.”

After his release, the FBI continued to monitor Hale. A document in the FBI files from 1956 stated that J. Edgar Hoover was living in Montana and worked at a “motor-restaurant-drive-in combination.” He’d also worked on a ranch and as a dishwasher at the Range Riders’ Bar and Café in recent years, according to the agent.

Hale died in a Phoenix nursing facility in August 1962 and was buried in Wichita, Kansas. The former King of the Osage Hills died at the age of 87.