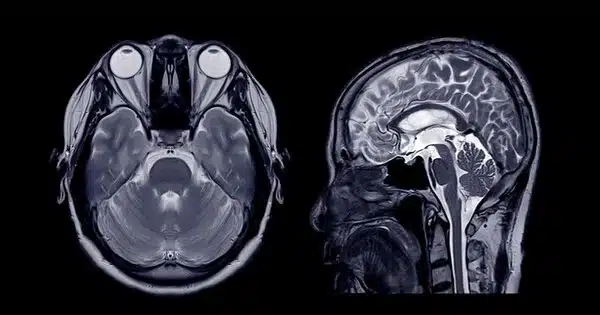

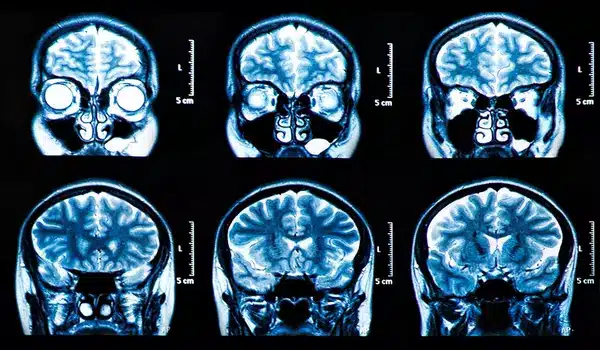

Researchers have used MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) to study brain changes and differences in children with ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder). ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects children and often persists into adulthood.

MRI studies have provided valuable insights into the structural and functional brain differences associated with ADHD. Scientists conducted a study to image the neural activity analogues to cognitive flexibility and discover differences in the brain activity of children with ADHD and those without.

Multitasking is not just an office skill. It’s key to functioning as a human, and it involves something called cognitive flexibility – the ability to smoothly switch between mental processes. UNC scientists conducted a study to image the neural activity analogues to cognitive flexibility and discover differences in the brain activity of children with ADHD and those without.

Their findings, in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, could help doctors diagnose children with ADHD and monitor the severity of the condition and treatment effectiveness.

We observed significantly decreased neural flexibility in the ADHD group at both the whole brain and sub-network levels, particularly for the default mode network, attention-related networks, executive function-related networks, and primary networks of the brain involved in sensory, motor and visual processing.

Weili Lin

Some people have greater cognitive flexibility than others. In some ways, it’s just the luck of the genetic draw, but we can improve our cognitive flexibility once we recognize we’re being rigid. Consider this: we are cognitively flexible when we can start dinner, let the onions simmer, text a friend, return to making dinner without scorching the onions, and then finish dinner while conversing with our spouse. We’re also cognitively flexible when we switch communication styles while talking to a friend, then a daughter, then a coworker, or when we solve problems creatively, such as when you realize you don’t have enough onions to make the dinner you want, and you need to come up with a new plan.

It’s part of our executive function, which includes accessing memories and exhibiting self-control. Poor executive function is a hallmark of ADHD in children and adults.

When we’re cognitively inflexible, we can’t focus on some of the tasks, we pick up the phone and scroll social media without thinking, forgetting what we’re doing while making dinner. In adults but especially in children, such cognitive inflexibility can wreak havoc with an individual’s ability to learn and accomplish tasks.

UNC scientists led by senior author Weili Lin, Ph.D., director of the UNC Biomedical Research Imaging Center (BRIC), wanted to find out what’s happening throughout the brain when executive function, particularly cognitive flexibility, is offline.

Lin and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study the neural flexibility of 180 children diagnosed with ADHD and 180 typically developing children.

“We observed significantly decreased neural flexibility in the ADHD group at both the whole brain and sub-network levels,” said Lin, the Dixie Boney Soo Distinguished Professor of Neurological Medicine in the UNC Department of Radiology, “particularly for the default mode network, attention-related networks, executive function-related networks, and primary networks of the brain involved in sensory, motor and visual processing.”

The researchers also found that children with ADHD who received medication exhibited significantly increased neural flexibility compared to children with ADHD who were not taking medication. Children on medication displayed neural flexibility that was not statistically different from the group of traditionally developing children.

Lastly, the researchers found that they could use fMRI to discover neural flexibility differences across entire brain regions between children with ADHA and traditionally developing children.

“And we were able to predict ADHD severity using clinical measures of symptom severity,” Lin said. “We think our study demonstrates the potential clinical utility of neural flexibility to identify children with ADHD, as well as to monitor treatment responses and the severity of the condition in individual children.”