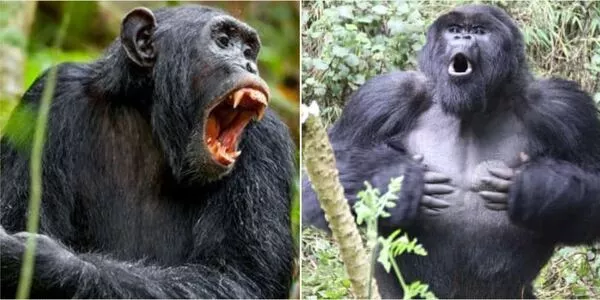

Researchers documented lasting social ties between individual chimps and gorillas that persisted over years and across different contexts in more than 20 years of observations at Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo. A long-term study led by Washington University in St. Louis primatologist Crickette Sanz reveals the first evidence of long-term social relationships between chimps and gorillas in the wild.

Researchers documented social ties between individual chimps and gorillas that persisted over years and across different contexts in more than 20 years of observations at Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo. Scientists from Washington University, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the University of Johannesburg (South Africa), and the Lincoln Park Zoo (Chicago) conducted the study, which was published in the journal iScience.

“There are few (if any) studies of interactions between primate species that have been able to take the identity of individuals into account,” said Sanz, a professor of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences. “It has long been known that these apes can recognize individual members of their own species and form long-term relationships, but we had not known that this extended to other species.

“An example of what we found might be one individual traveling through a group of the other species to seek out another particular individual,” she said. “We were also able to document such interactions over time and in different contexts in this study.”

While we remain concerned about many disease risks, we now know a lot more about the origins of many of these pathogens and the routes of their transmission within and between species, including humans.

Prof. Sanz

Most people are unaware that the majority of the remaining gorillas and chimps coexist. The Congo Basin’s vast forests protect not only these two types of endangered great apes, but also forest elephants, leopards, and a variety of other species. For nearly three decades, the government of the Republic of Congo and the Wildlife Conservation Society have collaborated to save wild places that sustain local people, protect natural resources, and mitigate global climate change.

Scientists documented ape species engaging in a wide range of social interactions, ranging from play to aggression, in a review of published reports combined with a synthesis of previously unpublished data about daily follows of chimps and gorillas in the Goualougo Triangle from 1999 to 2020. Researchers looked into several potential benefits of these interspecies encounters, such as protection from predation, improved foraging options, and other social benefits from information sharing.

What they discovered demonstrates that no ape is an island. “Rather than thinking about chimps in isolation, we should consider them in the context of diverse and dynamic habitats where they actively interact with other species and play an important role in the survival of the unique ecosystems in which they live” said co-author David Morgan, research fellow at Lincoln Park Zoo.

Why interact at all

One of the primary theories proposed for why apes may choose to associate with members of different species is to avoid predators. However, the information gathered in this study suggests that these social interactions cannot be attributed to threat reduction. The scientists discovered little evidence that chimps or gorillas are collaborating to reduce leopard, snake, or raptor predation attempts.

“Predation is definitely a threat in this region, as we have cases of chimps being killed by leopards,” Sanz said. “However, the number of chimps in daily subgroups remains relatively small, and gorillas within groups venture far away from the silverback, who is thought to be a predation protector.”

Instead, enhanced foraging opportunities seem to be more important. The researchers found that co-feeding at the same tree represented 34% of the interspecific associations that they documented, with another 18% of observations involving apes foraging in close spatial proximity but on different foods.

At least 20 different plant species were targeted by apes during co-feeding events in this study, greatly expanding researchers’ knowledge of the diversity of resources that chimpanzees and gorillas are willing to gather together to share.

In addition to a greater diversity of interactions than previously documented among sympatric apes, this study revealed social relationships between members of different species that persisted over years.

For example, study authors noted that on several occasions at food sources, they observed young gorillas and chimpanzees seeking out particular partners to engage in bouts of play. These types of interactions may afford unique development opportunities that extend the individual’s social, physical and cognitive competencies.

“No longer can we assume that an individual ape’s social landscape is entirely occupied by members of their own species,” said co-author Jake Funkhouser, a doctoral candidate of biological anthropology at Washington University. “The strength and persistence of social relationships that we observed between apes indicates a depth of social awareness and myriad social transmission pathways that had not previously been imagined. Such insights are critical given these interspecies social relationships have the potential to serve as transmission pathways for both beneficial socially learned cultural behaviors and harmful infectious disease.”

Concerns about disease transmission

Certainly, social interactions between apes pose risks. One example is the possibility of disease transmission. While poaching and habitat loss continue to be the most serious threats to apes, infectious disease has recently emerged as a threat of comparable magnitude.

Many pathogens can be transmitted between chimps and gorillas due to their close relationship. Ebola, for example, is a highly contagious virus that has wreaked havoc on ape populations in central Africa. Ebola first appeared in wild ape populations just over 20 years ago and then spread to humans. According to some estimates, the Ebola virus wiped out one-third of the world’s chimps and gorillas.

“While we remain concerned about many disease risks,” Sanz said, “we now know a lot more about the origins of many of these pathogens and the routes of their transmission within and between species, including humans.”

“The extent of overlap and interaction that occurred between these apes that was previously not recognized or reported,” she said of the findings. “We expected the apes to avoid each other based on the literature… and, in some cases, it appeared to be the inverse.”