According to new research, young people who consider themselves ‘multilingual’ outperform their peers in a variety of subjects, regardless of whether they are fluent in another language. A study of over 800 English students discovered a measurable, positive relationship between their personal connection to other languages and their GCSE exam results in both modern language and non-language subjects. This was true whether or not they spoke a second language fluently.

The study of over 800 English students discovered a positive relationship between GCSE scores and ‘multilingual identity,’ which refers to whether students felt a personal connection with other languages through knowledge and use. Those who identified as multilingual outperformed their peers not only in language subjects like French and Spanish, but also in non-language subjects like math, geography, and science. This was true whether or not they spoke a second language fluently.

Surprisingly, not all students who were officially labeled as having ‘English as a Second Language’ (EAL) by their schools thought of themselves as multilingual, despite the fact that the term is used by schools and the government as a proxy for multilingualism. Similarly, these students did not necessarily perform better (or worse) at GCSE as a group than their non-EAL peers.

The findings suggest that encouraging students to identify with languages and value different modes of communication may aid in the development of a mindset that promotes overall academic progress.

According to the evidence, the more multilingual you consider yourself to be, the higher your GCSE scores. While we need to learn more about why that relationship exists, it’s possible that children who see themselves as multilingual have a ‘growth mindset,’ which affects their overall achievement.

Dr. Dee Rutgers

Other recent research has argued for broadening the scope of language lessons so that, in addition to studying vocabulary and grammar, students investigate the significance of languages in their own lives. This new study, however, was the first to investigate the relationship between multilingual identity and attainment. The study was led by academics from the University of Cambridge, and the results were published in the Journal of Language, Identity, and Education.

Dr. Dee Rutgers, a Research Associate at the University of Cambridge’s Faculty of Education, stated: “According to the evidence, the more multilingual you consider yourself to be, the higher your GCSE scores. While we need to learn more about why that relationship exists, it’s possible that children who see themselves as multilingual have a ‘growth mindset,’ which affects their overall achievement.”

According to Dr. Linda Fisher, Reader in Languages Education at the University of Cambridge: “There may be a strong case to be made for assisting children who believe they cannot ‘do’ languages to recognize that we all use a variety of communication tools, and that learning a language simply adds to that range. This may have an impact on attitude and self-belief, which is directly related to school learning. In other words, what you believe about yourself may be more important than what others believe about you.”

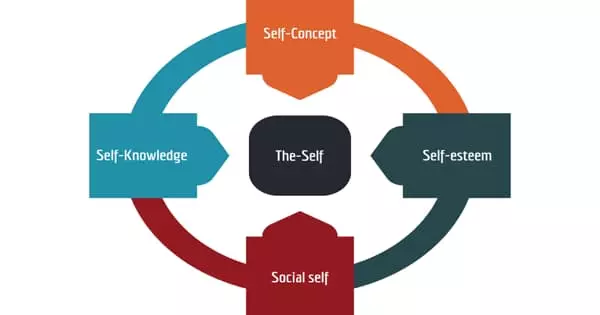

The authors of the study contend that being multilingual entails far more than the official EAL definition of being “exposed to a language at home that is known or believed to be other than English.” They argue that even young people who consider themselves monolingual have a “repertoire” of communication skills. For example, they may speak in different dialects, learn words and phrases while on vacation, understand sign language, or understand other types of ‘language’ such as computer code.

The research included 818 Year 11 students from five secondary schools in South East England. In addition to determining whether students were officially registered as EAL or non-EAL, the researchers asked each student if they identified as such. Each student was asked to chart where they saw themselves on a 0-100 scale, with 0 representing ‘monolingual’ and 100 representing ‘multilingual.’ This information was compared to their GCSE results in nine different subjects.

Students who spoke a second language at home did not always consider themselves to be EAL or multilingual. In contrast, students who perceived themselves to be multilingual were not always those identified by the school as having English as an additional language.

“It’s surprising that these terms didn’t correlate more closely, given that they’re all ostensibly measuring the same thing,” Rutgers said. “Clearly, having experience with other languages does not always translate into a multilingual identity because the experience may not be valued by the student.”

Although students who self-identified as EAL performed better than their peers in modern languages, school-reported EAL status had no effect on GCSE results. Those who rated themselves as’multilingual’ on a scale of 0 to 100 performed better academically across the board.

The strength of this relationship varied across subjects and was especially pronounced in modern languages. However, in all nine GCSE subjects examined, each point increase on the monolingual-to-multilingual scale was associated with a fractional increase in students’ exam scores.

A one-point increase, for example, was found to correspond to 0.012 of a grade in Science and 0.011 of a grade in Geography. Students who consider themselves to be very multilingual typically score a full grade higher than those who consider themselves to be monolingual. Positively identifying as multilingual may thus be sufficient to propel students who would otherwise fall slightly short of a certain grade level to the next level.

The findings appear to indicate that the positive mentality and self-belief that develops in students with a multilingual identity has spill-over benefits for their overall education. The authors go on to say that this can be fostered in language classrooms by exposing students to learning programs that explore different types of language and dialect, or by encouraging them to consider how languages shape their lives both inside and outside of school.

“Too often, we think of other languages as something we don’t need to know or as something that is difficult to learn,” Fisher said. “These findings suggest that encouraging students to see themselves as active and capable language learners could have a significant impact on their overall academic progress.”