Honey bees rely heavily on their sense of smell for foraging, navigation, and communication within the hive. Pesticides and adjuvants can disrupt these critical functions, potentially having a negative impact on the overall health and behavior of honey bee colonies. It has long been known that honey bees are harmed by pesticide sprays. A new study has revealed the effect of such sprays on bees’ sense of smell, which could disrupt their social signals.

Honey bees live in vibrant communities and are constantly communicating with one another via chemicals that act as social cues. Nurse bees, for example, who are in charge of caring for larvae that will eventually become queens and worker bees, constantly monitor the larvae in the dark using pheromones. To indicate that they require food, the larvae emit brood pheromones. Alarm pheromones are also produced by workers to warn other bees of impending danger. If these cues are muffled or misinterpreted, the colony may fail to thrive.

Honey bees have been in trouble since 2007, according to scientists. Insecticides, which affect honey bee health, are one of the stressors that have raised concerns. Because these are usually used in combination with other chemicals, the resulting mixture can become unexpectedly toxic to bees.

For many years, it was assumed that fungicides do not have an adverse impact on insects because they are designed for fungal targets. Surprisingly, in addition to insecticides, fungicides also have an adverse effect on bees and combining the two can disrupt colony function.

May Berenbaum

“For many years, it was assumed that fungicides do not have an adverse impact on insects because they are designed for fungal targets,” said May Berenbaum (GEGC/IGOH), a professor of entomology. “Surprisingly, in addition to insecticides, fungicides also have an adverse effect on bees and combining the two can disrupt colony function.”

Pesticide spray mixtures have been implicated in reports originating from almond orchards, where two-thirds of the United States’ honey bees are transported every year when the flowers are in bloom, for more than a decade. The issue is exacerbated by the use of ostensibly inactive chemicals known as adjuvants, which increase the “stickiness” of the insecticide so that it remains on the plants.

Adjuvants are not subjected to the same level of safety testing as other insecticidal agents because they have long been thought to be biologically benign. “Recently, researchers have shown that adjuvants alone or when used in combination with fungicides and insecticides are toxic to bees,” Berenbaum said in a press release.

These combinations are especially dangerous to nurse bees. “The health of the queens is paramount,” Berenbaum explained. “If healthy queens are not produced, the colony can suffer.”

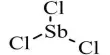

To better understand how combinations affect nurse bees, the researchers used the adjuvant Dyne-Amic, the fungicide Tilt, and the insecticide Altacor to test their effect on the olfactory system of honey bees.

The researchers divided bees into four groups of ten and exposed them for a week to either untreated commercial pollen or pollen treated with Dyne-Amic, Tilt and Altacor, or all three. The bees were then anesthetized on ice, and one antenna from each was carefully removed. The antenna was then exposed to chemical mimics of brood and alarm pheromones, and the researchers recorded the antenna’s response using a technique known as electroantennography.

With this method, Ling-Hsiu Liao, a research scientist, and Wen-Yen Wu, a graduate student, in the Berenbaum lab, found that when nurse bees had consumed pollen contaminated by the three chemicals, their antennal responses to some brood pheromones and alarm pheromones were altered. Their finding suggests that these commonly-used pesticides can interfere with honey bee communication.

It is still unknown how these chemicals interact with and affect bees. “There are many possible explanations for how consuming these chemicals can affect the sensory responses of bees,” Liao said in a statement. “The antenna detects and responds to olfactory signals.” We did not look at what other changes are triggered in this study, particularly changes in behavior.”

In addition to determining the underlying molecular pathways that are affected, the researchers want to test other pesticide mixtures and examine the response of bees in other populations. They hope that their research will prompt beekeepers to reconsider how they manage and protect their colonies.