Researchers present the findings of the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) of a BSL-4 virus. The researchers discovered two crucial human genetic variables that may explain why some people suffer severe Lassa fever, as well as a collection of LARGE1 variations associated with a lower risk of contracting Lassa fever. The findings could pave the way for improved treatments for Lassa fever and other related diseases. The researchers are currently doing a similar genetic investigation of Ebola susceptibility.

While searching through the human genome in 2007, computational geneticist Pardis Sabeti unearthed a finding that would change her scientific career. Sabeti, a postdoctoral scholar at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, identified probable evidence that an undiscovered mutation in a gene called LARGE1 had a positive influence on the Nigerian population. Other researchers revealed that this gene was necessary for the Lassa virus to enter cells. Sabeti wondered if a LARGE1 mutation could prevent Lassa fever, which is caused by the Lassa virus and is endemic in West Africa. It can be fatal in some people but very moderate in others.

To find out, Sabeti decided later in 2007, as a new faculty member at Harvard University, that one of the first projects her new lab at the Broad would take on would be a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of Lassa susceptibility. She reached out to her collaborator Christian Happi, now the Director of the African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) at Redeemer’s University in Nigeria, and together they launched the study.

Now, their groups and collaborators report the results of that study in Nature Microbiology — the first ever GWAS of a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) virus. The team found two key human genetic factors that could help explain why some people develop severe Lassa fever, and a set of LARGE1 variants linked to a reduced chance of getting Lassa fever. The work could lay the foundation for better treatments for Lassa fever and other similar diseases. The scientists are already working on a similar genetics study of Ebola susceptibility.

This really highlights the need for continued investment in understanding African population genetics. Even with a relatively limited sample set, we’ve increased our understanding of some African populations, specifically in immune-related genes – and that shows how much more there is to do going forward.

Siddharth Raju

The publication also outlines the several hurdles the researchers faced throughout their 16-year collaboration, such as researching a hazardous virus and recruiting patients with an illness that is not well documented in West Africa. Dozens of scientists worked on the project, spending seven years recruiting patients in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, as well as many more years developing the research program and assessing the results. “It truly took a village to get this done,” said Happi, a senior author with Sabeti.

“Generations of people in our labs, across different institutions and countries, spent significant parts of their careers bringing this to fruition,” added Sabeti, an institute member at the Broad, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, a professor at the Center for Systems Biology and the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, and a professor in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Disease at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

The co-first authors of the study are Dylan Kotliar, an internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an MD/PhD student in Sabeti’s lab while the project was ongoing; Siddharth Raju, a graduate student in Sabeti’s lab; Shervin Tabrizi, a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad; and Ikponmwosa Odia, a researcher at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital in Nigeria.

Lassa learnings

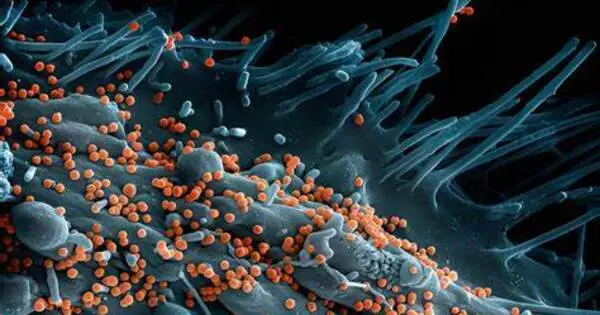

Sabeti recalls the team’s early discussions when launching the project. They knew they had to be cautious at every step: To work with a BSL-4 virus, scientists must wear pressurized suits connected to HEPA-filtered air in a special containment lab. The virus causes fever, sore throat, coughing, and vomiting, but can quickly progress to organ failure in some people.

“This was an extremely challenging study to get off the ground,” said Kotliar, who worked on the project throughout his entire PhD in the Sabeti lab. “I think the battle scars, the things we’ve learned along the way about how to get a project like this done, are going to be important for future research into viruses in developing countries.”

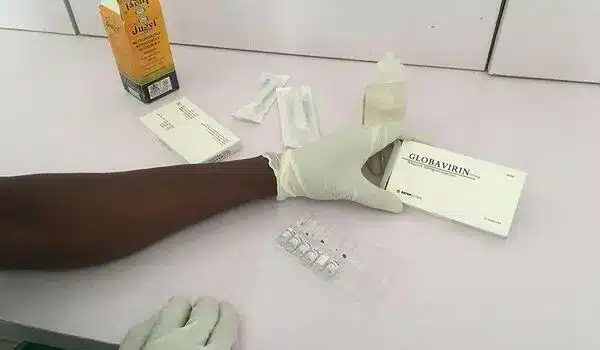

Finding participants for the study would be challenging too. There are currently no FDA-approved diagnostics for Lassa, and Lassa virus cases are typically not documented. There are fewer than 1,000 cases reported each year in Nigeria, the most populous country where the virus is endemic, and cases are often in rural areas far from diagnostic centers, many of which don’t have the technology to detect the virus. Infections with other viruses, and genomic complexity among different strains of the same Lassa virus can complicate analysis. Moreover, African populations have been historically underrepresented in past genetic studies, which reduces statistical power in data analyses and can make it difficult to identify key genetic variants.

When Sabeti began thinking about how to start the project, she reached out to Happi, whom she knew through their mutual work on the malaria-causing pathogen, Plasmodium falciparum. With the help of collaborators including Peter Okokhere, a doctor treating Lassa patients at the Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, they began recruiting patients from both Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Then, they compared the genomes of about 500 people who’d had Lassa fever and nearly 2,000 who hadn’t.

In the Nigerian cohort, the team discovered that people with a collection of mutations in the LARGE1 gene, which changes a cell receptor that attaches to particular viruses, were less likely to develop Lassa disease. Sabeti, Happi, and their colleagues also discovered genetic areas linked to Lassa fatality: the LIF1 gene, which encodes an immune-signaling protein, and, in the Nigerian cohort, the GRM7 gene, which is related in the central nervous system. The scientists next performed a large-scale screen known as a massively parallel reporter experiment to determine whether mutations within these genomic areas may be functional and could be targets for novel treatments.

Better detection

The researchers say that to improve detection and treatment of Lassa fever, more diagnostic centers and diagnostics that work in the field are needed, along with better health infrastructure to connect remote locations with major hospitals.

“This really highlights the need for continued investment in understanding African population genetics,” added Raju. “Even with a relatively limited sample set, we’ve increased our understanding of some African populations, specifically in immune-related genes — and that shows how much more there is to do going forward.”

Sixteen years after they first considered the genetics of Lassa fever, Sabeti and Happi are thrilled with the study’s findings, which may explain the biological variations between moderate and severe sickness. They added that the study demonstrates that genome-wide association studies of BSL-4 viruses are doable through deliberate international collaboration. The researchers have already started a similar Ebola study in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and other scientists are advocating for enhanced pathogen surveillance and scientific training in Africa.