The human brain’s development as it prepares for adulthood is heavily influenced by the learning environment provided during adolescence. As adolescents perform complex mental tasks, the neural networks that support those abilities grow stronger, improving their cognitive, emotion regulation, and memory abilities. As the brain matures, more fibers form and the brain becomes more interconnected. These interconnected networks of neurons are critical for memory formation and connecting new learning to previous learning. The child learns both academically and socially as neural networks form.

According to a new study of brain activity patterns in people performing a memory task, the way we make inferences (finding hidden connections between different experiences) changes dramatically as we age. The findings of the study could lead to personalized learning strategies based on a person’s cognitive and brain development in the future.

The researchers discovered that, whereas adults construct integrated memories with pre-programmed inferences, children and adolescents construct separate memories that they later compare to make on-the-fly inferences.

“How adults structure knowledge is not necessarily optimal for children because adult strategies may require brain machinery in children that are not fully mature,” said Alison Preston, professor of neuroscience and psychology and senior author of the study published today in the journal Nature Human Behaviour. She collaborated on the study with first author Margaret Schlichting, who was a doctoral student in Preston’s lab and is now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto.

The best thing a child can do in the absence of a mature memory system is laid down accurate, non-overlapping memory traces. Children can later recall those accurate memory traces to promote inferences about their connections.

Professor Alison Preston

Consider going to a daycare center to understand the difference between how adults and children make inferences. A child arrives with one adult in the morning but leaves with a different adult in the afternoon. You might infer that the two adults are the child’s parents and a couple, and your second memory would include both the second person you saw and information from your previous experience to make an inference about how the two adults – whom you didn’t actually see together – might relate to each other.

According to the findings of this new study, a child who has the same experiences as an adult is less likely to make the same kind of inference during the second experience. The two memories have less in common. If you ask your child to guess who that child’s parents are, he or she can still do it; all he or she has to do is recall the two distinct memories and then reason about how each adult might be related.

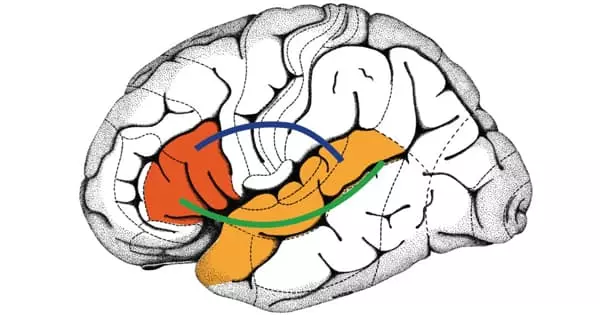

The neural machinery of children and adults differs, and the researchers believe that the strategy used by children may be optimal for the way their brains are wired before key memory systems in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex fully mature. This distinction may prevent children from recalling precious memories during new learning and limit their ability to connect events.

“The best thing a child can do in the absence of a mature memory system is laid down accurate, non-overlapping memory traces,” Preston said. “Children can later recall those accurate memory traces to promote inferences about their connections.”

The researchers asked 87 subjects ranging in age from 7 to 30 to look at pairs of images while lying in an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scanner, which measures brain activity by detecting small changes in blood flow with images that, as in the daycare example above, provide opportunities to infer relationships between objects that had not previously appeared together.

The researchers discovered that adolescents used a different strategy for making inferences than both young children and adults. Using the parents at the daycare as an example, when an adolescent stores a memory of the second grown-up with the child, the adolescent suppresses the earlier memory involving the first one. Each memory becomes more distinct than in younger children, and there are fewer automatic inferences about how the two adults interact.

“Teenagers’ learning strategies may be tuned to explore the world rather than exploit what they already know,” Preston said. This, as well as other findings from the study, could be used to develop strategies for improving teaching and learning at various ages. “From a brain maturation standpoint,” Preston explained, “different people will be at different places, and we can devise learning strategies that take advantage of the neural machinery that an individual has at hand, whether they are 7 years old or 70 years old.”