Many people who were fortunate enough to grow up with adoring grandmothers understand how they can enrich a child’s development in unique and valuable ways. For the first time, scientists have scanned grandmothers’ brains while they look at photos of their young grandchildren, providing a neural snapshot of this special intergenerational bond.

The first study to examine grand maternal brain function, conducted by Emory University researchers, is being published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

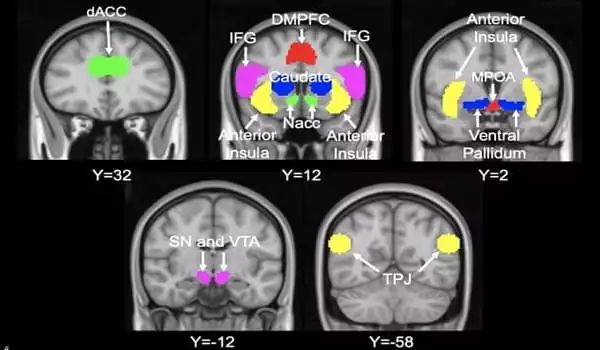

“What really stands out in the data is an activation in brain areas associated with emotional empathy,” says James Rilling, Emory professor of anthropology and study lead author. “This implies that grandmothers are wired to sense how their grandchildren are feeling when they interact with them. When their grandchild smiles, they feel the child’s happiness. And if their grandchild is crying, they are experiencing the child’s anguish and distress.”

In contrast, when grandmothers see images of their adult children, they show stronger activation in a brain area associated with cognitive empathy, according to the study. That suggests they are attempting to understand what their adult child is thinking or feeling and why, but not so much from an emotional standpoint.

“Young children have likely evolved traits that allow them to manipulate not just the maternal brain, but the grand maternal brain,” says Rilling. “Because an adult child lacks the same cute ‘factor,’ they may not elicit the same emotional response.”

What really stands out in the data is activation in brain areas associated with emotional empathy. This implies that grandmothers are wired to sense how their grandchildren are feeling when they interact with them. When their grandchild smiles, they feel the child’s happiness. And if their grandchild is crying, they are experiencing the child’s anguish and distress.

Professor James Rilling

Minwoo Lee, a PhD candidate in Emory’s Department of Anthropology, and Amber Gonzalez, a former Emory research specialist, are co-authors of the study. “I can personally relate to this research because I spent a lot of time interacting with both of my grandmothers,” Lee explains. “I remember the times I spent with them fondly. They were always friendly and delighted to see me. I didn’t understand why as a child.”

Lee adds that scientists studying the older human brain outside of dementia or other aging disorders is relatively uncommon. “Here, we’re highlighting grandmothers’ brain functions, which may play an important role in our social lives and development,” Lee explains. “It’s an important aspect of the human experience that has largely been overlooked by the field of neuroscience.”

Rilling’s lab studies the neural underpinnings of human social cognition and behavior. Other neuroscientists have conducted extensive research on motherhood. Rilling is a pioneer in the study of the little-studied neuroscience of fatherhood. Interactions between grandmothers and grandchildren provided new neural territory.

“In neuroscience, evidence for a global, parental caregiving system in the brain is emerging,” Rilling says. “We were curious to see how grandmothers fit into that pattern.” Humans are cooperative breeders, which means that mothers receive assistance in caring for their offspring, though the sources of that assistance vary across and within societies. “We often assume that fathers are the most important caregivers, second only to mothers,” Rilling says. “Grandmothers are often the primary caregivers in some cases.”

Indeed, the “grandmother hypothesis” proposes that human females tend to live long after their reproductive years because they provide evolutionary benefits to their offspring and grandchildren. This hypothesis is supported by a study of the traditional Hadza people of Tanzania, where grandmothers’ foraging improves the nutritional status of their grandchildren. Another study of traditional communities found that the presence of grandmothers reduces the interbirth intervals of their daughters while increasing the number of grandchildren.

In more modern societies, evidence is accumulating that positively engaged grandmothers are associated with better outcomes for children on a variety of measures, including academic, social, behavioral, and physical health.

The researchers wanted to understand the brains of healthy grandmothers and how that might relate to the benefits they provide to their families for the current study. The study’s 50 participants filled out questionnaires about their experiences as grandmothers, detailing things like how much time they spend with their grandchildren, the activities they do together, and how much affection they have for them.

They were also subjected to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to assess their brain function while viewing images of their grandchild, an unknown child, the grandchild’s same-sex parent, and an unknown adult.

The findings revealed that when participants saw pictures of their grandchildren, they showed more activity in brain areas associated with emotional empathy and movement than when they saw other images.

Grandmothers who more strongly activated areas associated with cognitive empathy when viewing pictures of their grandchildren expressed a desire for greater involvement in caring for the grandchildren in the questionnaire.

Finally, when compared to the results of an earlier study by the Rilling lab of fathers viewing photos of their children, grandmothers activated more strongly regions involved with emotional empathy and motivation when viewing images of their grandchildren.

“Our findings add to the growing body of evidence that there appears to be a global parenting caregiving system in the brain, and that grandmothers’ responses to their grandchildren map onto it,” Rilling says. According to the researchers, one limitation of the study is that the participants are skewed toward mentally and physically healthy women who are high-functioning grandmothers.

The study raises a slew of new questions that must be addressed. “It would be interesting to look at grandfather neuroscience and how the brain functions of grandparents may differ across cultures,” Lee says.

Rilling found personally interviewing all of the participants to be a particularly rewarding aspect of the project. “It was a lot of fun,” he says. “I wanted to get a sense of the joys and difficulties of being a grandmother.”

Many of them reported that the most difficult challenge was not interfering when they disagreed with the parents about how their grandchildren should be raised and what values they should instill in them.

“Many of them also mentioned how nice it is not to be under as much time and financial pressure as they were when they were raising their children,” Rilling says. “They get to enjoy being a grandmother far more than they did being parents.”