A new study by Yale undergraduate Chase Doran Brownstein describes two dinosaurs that lived around 85 million years ago in Appalachia, a once-isolated land mass that now comprises much of the eastern United States: an herbivorous duck-billed hadrosaur and a carnivorous tyrannosaur. The findings were published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

The two dinosaurs, described by Brownstein from specimens housed at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, help fill a major gap in the North American fossil record from the Late Cretaceous period and provide evidence that dinosaurs in the eastern portion of the continent evolved independently of their counterparts in western North America and Asia, according to Brownstein.

“These specimens illuminate certain mysteries in the eastern North American fossil record and help us better understand how geographic isolation—large water bodies separated Appalachia from other landmasses—affected dinosaur evolution,” said Brownstein, a junior at Yale College. “They’re also a good reminder that, while the western United States has long been the source of exciting fossil discoveries, the eastern part of the country has its own treasures.”

Peabody dinosaur fossils shed light on the evolution of dinosaurs in eastern North America. Tyrannosaurus rex, the fearsome predator that once roamed what is now western North America, appears to have had an East Coast cousin.

For the majority of the Cretaceous period, which ended 66 million years ago, North America was divided into two land masses, Laramidia in the west and Appalachia in the east, separated by the Western Interior Seaway. While well-known dinosaurs such as T. rex and Triceratops roamed Laramidia, little is known about the animals that lived in Appalachia. Brownstein explained that one reason is that Laramidia’s geographic conditions were more conducive to the formation of sediment-rich fossil beds than Appalachia’s.

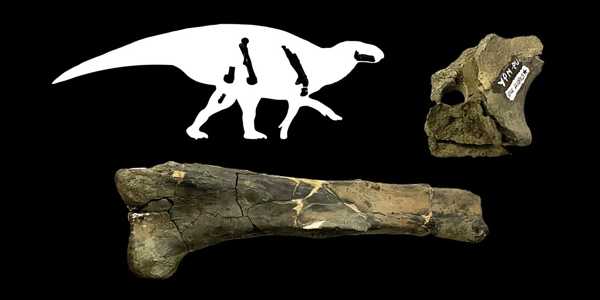

The new study’s specimens were discovered primarily in the 1970s at the Merchantville Formation in present-day New Jersey and Delaware. They are one of North America’s only known dinosaur assemblages from the late Santonian to early Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous. Brownstein noted that the fossil record from 85 to 72 million years ago is limited.

Brownstein examined the partial skeleton of a large predatory therapod and concluded that it is most likely a tyrannosaur. He noted that the fossil shares several features in its hind limbs with Dryptosaurus, a tyrannosaur that lived in what is now New Jersey about 67 million years ago. The dinosaur’s hands and feet differ from those of T. rex, including massive claws on its forelimbs, implying that it belongs to a separate family of predators that evolved solely in Appalachia.

“Many people believe that in order to become apex predators, all tyrannosaurs must have evolved a specific set of features,” Brownstein said. “Our fossil suggests that they evolved into giant predators in a variety of ways, as it lacks key foot or hand features associated with western North American or Asian tyrannosaurs.”

Brownstein discovered that the partial skeleton of a hadrosaur provided important new information on the evolution of the shoulder girdle in that group of dinosaurs. The hadrosaur fossils also provide one of the best records of this group from east of the Mississippi and include some of the region’s only infant/perinate (very young) dinosaur fossils.

Brownstein, a research associate at the Stamford Museum and Nature Center in Stamford, Connecticut, has previously published his paleontological work in peer-reviewed journals such as Scientific Reports, the Journal of Paleontology, and the Zoological Journal of the Linnaean Society. He is currently working on the evolution of fishes, lizards, and birds, in addition to eastern North American fossils. He is particularly curious about how geographic change and other factors influence how quickly different types of living things evolve.

He is currently a research assistant in the lab of Thomas J. Near, curator of the Peabody Museum’s ichthyology collections and professor and chair of Yale’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Brownstein also works in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences with Yale paleontologists Jacques Gauthier and Bhart-Anjan Bhullar.

While Brownstein is considering a career in academia, he says his research is motivated by a desire to have fun. “It makes me happy to do research and think about these things,” he said. “Like biking, it’s something I enjoy doing.”