In addition to increased morbidity and impaired lung function following a Streptococcus pneumonia infection in older mice, the researchers discovered elevated levels of gut-derived bacteria in the lungs, implying that bacteria migrating from the intestine to the lungs may contribute to poor outcomes in the elderly.

Why are elderly people more prone to become extremely ill or perhaps die as a result of pneumonia? The cause, it turns out, may have as much to do with the gut as it does with the lungs. According to a recent study led by Rachel McMahan, PhD, assistant research professor of GI, trauma, and endocrine surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and Holly Hulsebus, a CU School of Medicine immunology graduate student.

In a paper published in March in the journal Frontiers in Aging, the researchers — along with senior author Elizabeth J. Kovacs, PhD, professor of GI, trauma, and endocrine surgery — looked at the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniaein in animal models, studying changes in intestinal microbial populations after infection.

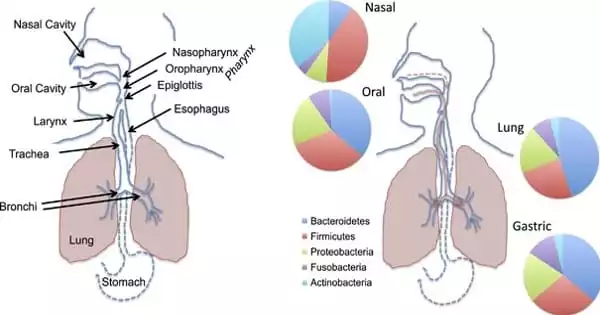

“Streptococcus pneumoniae is commonly found in the nasal passages of healthy persons. People with healthy immune systems may just live with it, and it causes no difficulties” Hulsebus explains. “People with weakened immune systems, such as the elderly, are more vulnerable because their immune systems are unable to regulate the microorganisms that are regularly present. These germs can exit the nose and travel to other parts of the body. They can cause ear infections, as well as move to the lungs and cause pneumonia.”

Our basic assumption is that as you become older, you have a higher baseline inflammatory response, which causes the gut to become more pro-inflammatory. That causes potentially pathogenic bacteria in the gut to leak out into the organs, and then things can go downhill fast.

Elizabeth J. Kovacs

The role of the leaky gut

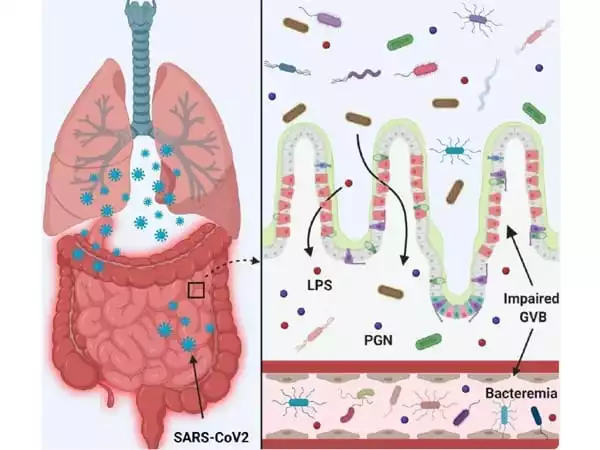

In addition to increased morbidity and impaired lung function following a Streptococcus pneumonia infection in older mice, the researchers discovered elevated levels of gut-derived bacteria in the lungs, implying that bacteria migrating from the intestine to the lungs may contribute to poor outcomes in the elderly.

According to McMahan, one likely reason for this migration is because as we age, our intestines become “leaky” as the body’s mechanisms for keeping gut bacteria in place begin to break down. This is identical to what occurs to burn trauma sufferers and alcoholics. Complicating matters, inflammation in the body naturally increases with age, resulting in an increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria in the gut.

The researchers discovered elevated levels of the Enterobacteriaceaefamily of bacteria — a gut-specific bacteria that includes E. coli — in the lungs of aged, but not young, animal models infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae in their published study, which was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. Because Enterobacteriaceae has been linked to increased inflammation, the researchers found larger amounts of neutrophils, a kind of inflammatory immune cell, in the lungs of the older infected animal models.

“Our basic assumption is that as you become older, you have a higher baseline inflammatory response, which causes the gut to become more pro-inflammatory,” McMahan adds. “That causes potentially pathogenic bacteria in the gut to leak out into the organs, and then things can go downhill fast.”

New strategies for fighting infection

Depending on co-morbidities or underlying health issues, older persons are approximately five times more likely to be hospitalized following a pneumonia infection, and fatality rates from pneumonia can surpass 50%. With the global population of persons over the age of 65 constantly increasing, it is critical to develop innovative methods of combating serious illness.

According to McMahan, focusing on the gut may help researchers uncover novel ways to prevent increased inflammation in the lungs. Probiotics and a balanced diet, she says, could help keep gut flora in check in the elderly, as could medications that prevent gut leakiness. Future research in the lab includes investigating the effectiveness of microbiome transplants or fecal transplants that replace the bacteria in the aging gut with that of younger animals.

The gut-lung axis has long been investigated in the context of disorders such as acute respiratory stress disorder, but the new work from CU School of Medicine researchers is among the first to show how aging can contribute to the problem.

“We’re showing that as you age, you specifically have increase of these bacteria, and that the gut-lung axis may be disrupted,” McMahan says.