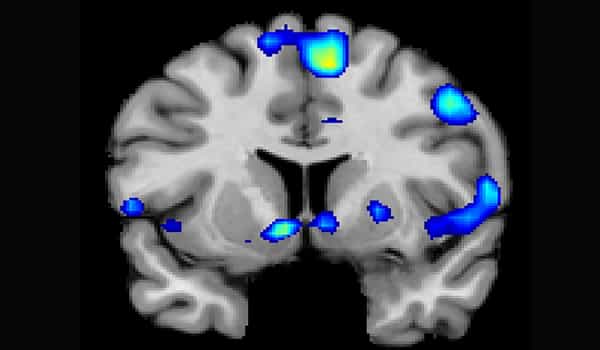

Scientists have long suspected that religiosity and spirituality are linked to specific brain circuits, but the exact location of those circuits is unknown. A new study has identified a brain circuit that appears to mediate that aspect of our personality using novel technology and the human connectome, a map of neural connections. Elsevier publishes the study in Biological Psychiatry.

The study, led by Michael Ferguson, Ph.D., an investigator in the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA, USA, demonstrates that spirituality’s brain circuitry revolves around a brainstem area known as the periaqueductal gray (PAG).

“Patients frequently report that spiritual and religious experiences are among the most meaningful events in their lives. However, medical science has historically been hesitant to empirically study the effects of spirituality or its physiological mechanisms, according to Dr. Ferguson.

“We are now at a point in science where there is enough cultural openness in science combined with threshold technological proficiency in brain mapping that we don’t need to be so shy about examining spirituality using our best scientific methods.”

Researchers find a region of the brain stem called the periaqueductal gray may mediate religiosity and spirituality in humans. A new study using novel technology and the human connectome, a map of neural connections, has identified a brain circuit that seems to mediate that aspect of our personality.

Some people with neurological diseases, such as schizophrenia, have religious or spiritual hallucinations or ideas. Previous research has also shown that people with a specific type of epilepsy or damage to specific brain areas may experience changes in their spiritual identification.

Earlier research has also suggested that religious experiences are not the result of a single brain region – that there is no so-called “god spot” – but that spirituality is most likely the result of dynamic activity across multiple brain regions.

Dr. Ferguson and colleagues examined previously collected data on self-reported spirituality from 88 patients before and after brain tumor surgery to map the newly discovered brain circuit. Using a connectome dataset, the researchers then used a technique known as lesion network mapping to examine how the site of each patient’s lesion, or tumor, interacts with the rest of the brain. The PAG was identified as a critical hub for changes in spiritual identification as a result of the analysis.

Dr. Ferguson and his colleagues then confirmed the significance of the PAG by analyzing previously collected data from 105 Vietnam War veterans who had suffered head trauma. The PAG is an ancient brain structure known for its roles in fear response behaviors and autonomic functions such as heart rate regulation. The PAG is perhaps best known (and most studied) for its role in pain relief via the release of endogenous opioids, the brain’s own painkillers.

Dr. Ferguson and his colleagues were surprised to discover that the spirituality circuitry was centered on the PAG rather than “higher” brain regions such as the cortex, which is typically associated with cognitive function and abstract thoughts.

“The fact that our findings in this study point to such an evolutionarily ancient brainstem structure to define a circuit for spirituality is potentially significant for a variety of reasons,” Dr. Ferguson added. One of the more obvious material reasons is that the [PAG] is well-known for mediating pain inhibition. This piques my interest in how spirituality might be clinically relevant for assisting with the management of physical and emotional pain.

“The fact that the [PAG] is involved in attachment and bonding may also point to mechanistic explanations for the emerging observation that spirituality can be effectively integrated into psychotherapy.” These are, of course, preliminary speculations about possible clinical relevance for the neuroscience of spirituality; however, the fact that there is so much more work to be done in this area is both exciting and motivating!”

“It is important to understand that this study does not suggest that religion or spirituality in healthy people are in any way abnormal,” said John Krystal, MD, Editor of Biological Psychiatry, of the findings. Rather, this research identifies brain circuits that allow us to have religious or spiritual experiences.

Researchers have long suspected the existence of these circuits because some mental and neurologic illnesses have been linked to changes in religious experiences, such as religious hallucinations or delusions. The study by Dr. Ferguson and colleagues, on the other hand, now maps the brain circuits involved in religious experience and spirituality with unprecedented precision.