In a therapeutic setting, psilocybin, the active compound in magic mushrooms, maybe at least as effective as a leading antidepressant medication. This is the conclusion of a study conducted by researchers at Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research.

A new phase II clinical study compared psilocybin, the active compound in psychedelic mushrooms, to a standard selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant to see which was a better treatment for depression and psilocybin appears to have held its own.

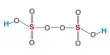

Researchers compared two sessions of psilocybin therapy with a six-week course of a leading antidepressant (a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor called escitalopram) in 59 people with moderate-to-severe depression in the most rigorous trial to date assessing the therapeutic potential of a ‘psychedelic’ compound.

Psilocybin, the active compound in magic mushrooms, may be at least as effective as a leading antidepressant medication in a therapeutic setting. Psilocybin performed about as well as the SSRI escitalopram as a treatment for moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder.

According to a double-blind, randomized trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine, psilocybin performed about as well as the SSRI escitalopram as a treatment for moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder. And in some ways, it may have outperformed it.

“When given by professional therapists, psilocybin therapy appears to be at least as effective as a leading conventional antidepressant and is faster acting with a reassuring safety profile,” lead study author and head of Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research Robin Carhart-Harris told PsyPost.

The researchers do warn, however, that the main comparison between psilocybin and the antidepressant was not statistically significant. They go on to say that larger trials with more patients over a longer period of time are needed to determine whether psilocybin can perform as well as, or better than, an established antidepressant.

Because the researchers did not want the participants’ perceptions of an either drug to influence their results, they concealed which drug each subject received. Half of the participants received a placebo pill in place of their SSRI pill but a full dose of psilocybin, while the other half received an insignificantly small amount of psilocybin and a genuine SSRI pill. In essence, each participant was only treated with one of the two drugs but had no idea which one they were taking.

The study itself was quite small only a few dozen people completed it so more extensive research will be required before psilocybin can be granted the same level of regulatory approval as an SSRI. However, given the numerous challenges of conducting psilocybin research in a safe, legal, and comprehensive manner, as Carhart-Harris previously detailed to Futurism, this study is still quite impressive.

“Our previous research in treatment-resistant depression and human brain scanning strongly suggested that psilocybin has therapeutic potential,” Carhart-Harris told PsyPost. “Putting psilocybin up against a traditional antidepressant felt like a brave and interesting test to do.”

While the findings are generally positive, the lack of a straight placebo group and the small number of participants limit conclusions about the effect of either treatment alone, according to the team. They also point out that the trial sample was predominantly white, male, and relatively well-educated, which limits extrapolation to more diverse populations.

The psilocybin group had fewer cases of dry mouth, anxiety, drowsiness, and sexual dysfunction than the escitalopram group, but had a similar overall rate of adverse events. The most common side effect of psilocybin was headaches one day after dosing sessions.

“Context is critical for these studies, and all volunteers received therapy during and after their psilocybin sessions,” said Dr Rosalind Watts, clinical lead of the trial and formerly based at the Centre for Psychedelic Research. Our therapists were on hand to provide full support during some difficult emotional experiences.”

“These findings provide further support for the growing evidence base that shows that in people with depression, psilocybin offers an alternative treatment to traditional antidepressants,” said Professor David Nutt, principal investigator on the study and the Edmond J Safra Chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial.