No contraceptive method is perfect, and scientists are constantly looking for safer, more effective alternatives. Researchers have discovered a method to trap sperm in its natural gel state, and they believe their findings may pave the way for a new type of birth control. Normally, after ejaculation, semen liquefies, allowing sperm to swim through a woman’s reproductive system and fertilize an egg. The researchers discovered that blocking a protein in sperm called prostate-specific antigen (PSA) causes it to remain in its thick gel form, trapping the majority of sperm.

A discovery that inhibits the normal transition of sperm from a thick gel to a liquid holds promise for the development of a new non-hormonal, over-the-counter contraception method. A recent study found that blocking a prostate-specific antigen in human ejaculate samples caused the sperm to stay in its thick gel form, trapping the majority of the sperm.

A team led by Washington State University discovered that blocking prostate-specific antigens in human ejaculate samples caused the sperm to remain in its thick gel form, trapping the majority of the sperm. Normally, the sperm will liquefy and swim through the female reproductive system to fertilize an ovum or egg. The discovery, which can halt the process, was published in the journal Biology of Reproduction.

Our goal is to develop this into an easily accessible female contraceptive that would be available on-demand, meaning women could go buy it off the shelf. It could be used in conjunction with a condom to significantly reduce failure rates.

Joy Winuthayanon

“Our goal is to develop this into an easily accessible female contraceptive that would be available on-demand, meaning women could go buy it off the shelf,” said senior author Joy Winuthayanon, associate professor and director of WSU’s Center for Reproductive Biology. “It could be used in conjunction with a condom to significantly reduce failure rates.”

Currently, the failure rate of over-the-counter contraceptives such as condoms and spermicides ranges from 13% to 21%, according to the study’s authors. Hormonal-based contraceptives, such as IUDs and birth control pills, have lower failure rates, but they can have side effects and are not always easily available or affordable, which may be one reason why the global unintended pregnancy rate is currently 48 percent, according to recent global health research.

The WSU team has been working on this contraceptive method since 2015, when it was discovered that some of the female mice in a different reproductive study were unable to become pregnant; upon further investigation, the researchers discovered that the male’s semen was remaining in solid form. The researchers then attempted to deliberately stop the sperm liquefication process in mice, and using a non-specific protease inhibitor called AEBSF, they were able to disrupt sperm movement and reduce fertility in mice, as detailed in an earlier Biology of Reproduction paper.

The current study’s research team attempted to translate those findings to human samples. They discovered that AEBSF had a contraceptive effect, but it was unclear whether this was due to toxicity. The researchers then used an antibody to specifically target the prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, in human sperm. They chose PSA as the primary active protein in liquefication and because it is secreted in large quantities from the prostate gland, which is present in humans but not in mice.

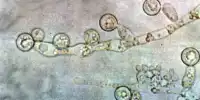

Typically, after ejaculation, the PSA acts on the gel-forming proteins known as semenogelins, according to first author Prashanth Anamthathmakula, who worked on the project as a WSU post-doctoral fellow.

“The semenogelins form a gel-like network with a fine protein mesh that traps the sperm. The PSA cleaves the mesh, allowing the sperm to escape “Anamthathmakula, who is now a senior research scientist at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, explained this. “We demonstrated that we could block that liquefaction using a PSA inhibitor, an antibody.”

The next step is to find more specific small molecule inhibitors that would effectively prevent PSA from liquefying sperm without causing any negative side effects. Current spermicides have been shown to reduce natural vaginal barriers to sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, according to the researchers. This advancement could avoid that type of toxicity by targeting the liquefaction process of the semen itself, but more research is needed.

“It’s a lengthy process because we don’t want off-target effects,” Winuthayanon explained. “If we develop this into a contraceptive product, it may be something that women use frequently, so we want something that is safe and has no unintended consequences.”