Evolution is the process of heritable change in populations of organisms over multiple generations. Evolutionary biology is the study of this process, which can occur through mechanisms such as natural selection, sexual selection, and genetic drift. According to surprising new research, gills played an early and equally important role in regulating the salt and pH balance of blood long before they evolved to help vertebrates breathe underwater.

Gills are best known for assisting the majority of fish species in breathing underwater. However, it is less well known that gills regulate the salt and pH balance of fish blood, a role that the kidneys play in other animals. Collectively known as ion regulation, this lesser-known gill function has been traditionally thought to have evolved in tandem with breathing. But surprising new research published in Nature is adding a new, early chapter to the evolutionary story of gills.

“Our work suggests that the early, simplified gills of our worm-like ancestors played an important role in ion regulation. And that role might have originated as early as the very inception of gills, well before they played any role in breathing,” says Dr. Michael Sackville, a zoologist who led the study while with the University of British Columbia (UBC).

“This really does flip the script on our understanding of how gills and gill function evolved.”

We discovered that gills were only used for breathing in our vertebrate representative, and only with increasing body size and activity. Our work suggests that the early, simplified gills of our worm-like ancestors played an important role in ion regulation. And that role might have originated as early as the very inception of gills, well before they played any role in breathing.

Dr. Colin Brauner

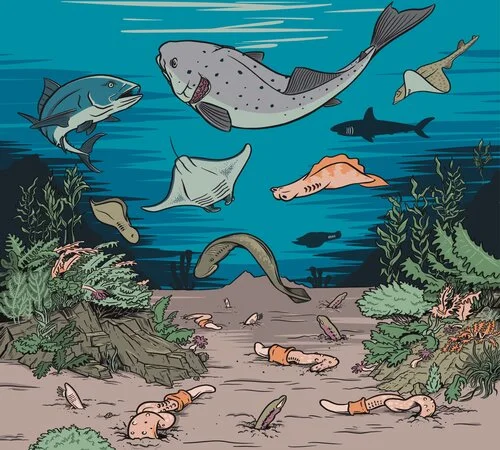

For more than a century, biologists, including Darwin, have been fascinated by the evolution of gills and lungs. Prior to this research, it was thought that gills were first used for breathing and ion regulation near the beginning of vertebrate life. These two functions shifted from the skin to the gills in tandem in this traditional timeline, assisting vertebrates in their transition from small, worm-like creatures to larger, active fishes. This transformation from “small and wormy” to “big and fishy” is a watershed moment in vertebrate evolution.

Humans are gnathostomes, or jawed vertebrates, which account for 99.8% of all extant vertebrate species. The basic body plan and several key organs of humans can be traced back to the origin of gnathostomes. The evolution of jaws is one of the most significant developments in vertebrate evolution.

The study traced the evolutionary journey of gills by comparing three animals that are alive today, but belong to different lineages: lampreys, which are vertebrates, and amphioxus and acorn worms, which are close relatives of vertebrates. The researchers assumed that any gill functions shared between the animals were inherited from a common ancestor, which is believed to be when simple gills first appeared well over 500 million years ago.

“We discovered that gills were only used for breathing in our vertebrate representative, and only with increasing body size and activity,” says Dr. Colin Brauner, a UBC zoologist and senior author on the paper.

“However, we discovered ion regulating cells in the gills of all three of our animals. This allowed us to trace the evolution of ion regulation at gills all the way back to early deuterostome animals, when very simple gill structures are thought to have first evolved. The discovery supports the classic story that gills were first used for breathing in early vertebrates, but it also adds an exciting new, earlier chapter to the story that is clearly worthy of further investigation.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with researchers at the University of Montreal and Cambridge University, and funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada and Royal Society.