Black holes are the Universe’s most extreme objects. Supermassive versions of these inconceivably dense objects are most likely found at the cores of all large galaxies. Stellar-mass black holes, which weigh between five and one hundred times the mass of the Sun, are far more common, with an estimated 100 million in the Milky Way alone. Only a few have been confirmed so far, and nearly all of them are ‘active,’ which means they glow brightly in X-rays as they consume material from a nearby stellar companion, as opposed to dormant black holes, which do not.

Astronomers using the International Gemini Observatory, which is run by the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab, discovered the closest-known black hole to Earth. The discovery of a dormant stellar-mass black hole in the Milky Way is the first unambiguous detection. Its close proximity to Earth, only 1600 light-years away, makes it an intriguing target for research into the evolution of binary systems.

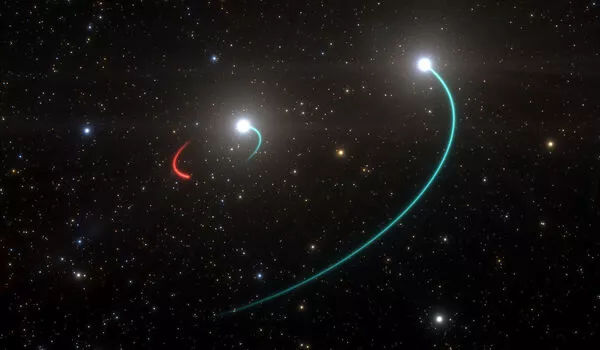

Astronomers using the Gemini North telescope on Hawai’i, one of the twin telescopes of the InternationalGemini Observatory, operated by the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab, have discovered the closest black hole to Earth, dubbed Gaia BH1. This dormant black hole is approximately 10 times more massive than the Sun and is located approximately 1600 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, bringing it three times closer to Earth than the previous record holder, an X-ray binary in the constellation Monoceros. The new discovery was made possible by meticulously observing the motion of the black hole’s companion, a Sun-like star that orbits the black hole at approximately the same distance as the Earth orbits the Sun.

“Take the Solar System, put a black hole where the Sun is, and the Sun where the Earth is, and you get this system,” explained Kareem El-Badry, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonianand the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, and the lead author of the paper describing this discovery. “While there have been many claimed detections of systems like this, almost all these discoveries have subsequently been refuted. This is the first unambiguous detection of a Sun-like star in a wide orbit around a stellar-mass black hole in our Galaxy.”

Our Gemini follow-up observations confirmed beyond reasonable doubt that the binary contains a normal star and at least one dormant black hole. We could find no plausible astrophysical scenario that can explain the observed orbit of the system that doesn’t involve at least one black hole.

El-Badry

Though there are probably millions of stellar-mass black holes in the Milky Way Galaxy, the few that have been discovered were discovered through their energetic interactions with a companion star. As material from a nearby star spirals in toward the black hole, it becomes superheated, causing powerful X-rays and material jets to form. When a black hole is not actively feeding, it simply disappears into its surroundings.

“I’ve spent the last four years looking for dormant black holes using a variety of datasets and methods,” El-Badry explained. “Previous attempts, as well as those of others, have yielded a slew of binary systems masquerading as black holes, but this is the first time the hunt has yielded fruit.”

The team originally identified the system as potentially hosting a black hole by analyzing data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft. Gaia captured the minute irregularities in the star’s motion caused by the gravity of an unseen massive object. To explore the system in more detail, El-Badry and his team turned to the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph instrument on Gemini North, which measured the velocity of the companion star as it orbited the black hole and provided precise measurement of its orbital period. The Gemini follow-up observations were crucial to constraining the orbital motion and hence masses of the two components in the binary system, allowing the team to identify the central body as a black hole roughly 10 times as massive as our Sun.

“Our Gemini follow-up observations confirmed beyond reasonable doubt that the binary contains a normal star and at least one dormant black hole,” elaborated El-Badry. “We could find no plausible astrophysical scenario that can explain the observed orbit of the system that doesn’t involve at least one black hole.”

The team relied not only on Gemini North’s excellent observational abilities, but also on Gemini’s ability to provide data on a tight deadline, as the team only had a short window in which to conduct their follow-up observations.

“We only had one week before the two objects were at their closest separation in their orbits when we received the first indications that the system contained a black hole. Measurements at this point are critical for estimating mass accurately in a binary system “El-Badry stated. “The ability of Gemini to provide observations in a short period of time was critical to the project’s success. We would have had to wait another year if we had missed that narrow window.”

Astronomers’ current models of the evolution of binary systems are hard-pressed to explain how the peculiar configuration of Gaia BH1 system could have arisen. Specifically, the progenitor star that later turned into the newly detected black hole would have been at least 20 times as massive as our Sun. This means it would have lived only a few million years. If both stars formed at the same time, this massive star would have quickly turned into a supergiant, puffing up and engulfing the other star before it had time to become a proper, hydrogen-burning, main-sequence star like our Sun.

It is not at all clear how the solar-mass star could have survived that episode, ending up as an apparently normal star, as the observations of the black hole binary indicate. Theoretical models that do allow for survival all predict that the solar-mass star should have ended up on a much tighter orbit than what is actually observed.

This could imply that there are significant gaps in our understanding of how black holes form and evolve in binary systems, as well as the existence of a previously unknown population of dormant black holes in binary systems.

“It’s fascinating that this system isn’t easily accommodated by standard binary evolution models,” El-Badry concluded. “It begs the question of how this binary system came to be, as well as how many of these dormant black holes exist out there.”

“As part of a network of space- and ground-based observatories, Gemini North has not only provided strong evidence for the nearest black hole to date, but also the first pristine black hole system, free of the usual hot gas interacting with the black hole,” said Martin Still, NSF Gemini Program Officer. “While this may portend future discoveries of our Galaxy’s predicted dormant black hole population, the observations also leave a mystery to be solved: why is the companion star in this binary system so normal, despite a shared history with its exotic neighbor?”