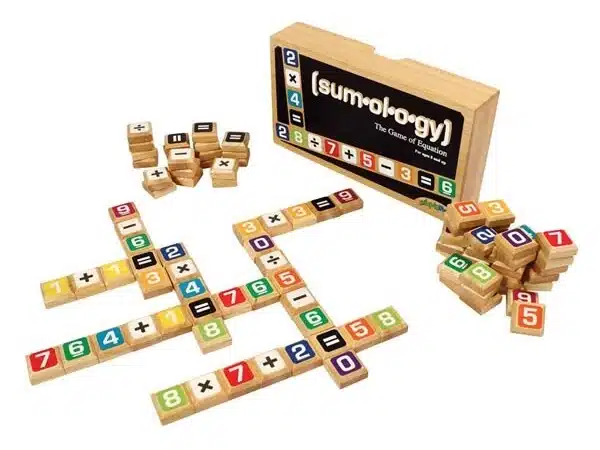

Board games need a variety of mathematical principles, including counting, addition, subtraction, strategic thinking, and problem-solving. According to a comprehensive analysis of research published on the topic over the previous 23 years, board games focused on numbers, such as Monopoly, Othello, and Chutes and Ladders, make young children better at math.

Board games have long been acknowledged to improve learning and development, particularly reading and literacy. This new study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Early Years, discovers that the format of number-based board games helps three to nine-year-olds improve counting, addition, and the capacity to detect if one number is higher or lower than another.

According to the researchers, children benefit from programs – or interventions – in which they play board games a few times each week while being supervised by a teacher or another qualified adult. “Board games improve young children’s mathematical abilities,” says main author Dr. Jaime Balladares of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago, Chile.

“Using board games as a strategy can have an impact on basic and complex math skills. Learning objectives relating to mathematics skills or other areas can be easily included into board games.”

Board games improve young children’s mathematical abilities,” says main author Dr. Jaime Balladares of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago, Chile.

Using board games as a strategy can have an impact on basic and complex math skills. Learning objectives relating to mathematics skills or other areas can be easily included into board games. Board games improve young children’s mathematical abilities.

Dr. Jaime Balladares

Games in which players take turns moving pieces around a board differ from those in which specific talents or gambling are involved. The rules of a board game are fixed, limiting a player’s activities, and the moves on the board usually affect the entire playing situation. However, board games are rarely used in preschools. The goal of this study was to synthesize all relevant data of their impacts on children.

The researchers set out to determine the extent to which physical board games promote learning in young children. They based their findings on a study of 19 research published between 2000 and 2010 that involved children aged three to nine years. Except for one, all of the studies looked at the association between board games and mathematical abilities.

All children participating in the studies received special board game sessions which took place on average twice a week for 20 minutes over one-and-a-half months. Teachers, therapists, or parents were among the adults who led these sessions. In some of the 19 studies, children were grouped into either the number board game or to a board game that did not focus on numeracy skills. In others, all children participated in number board games but were allocated different types e.g. Dominoes.

All of the children were tested on their math skills before and after the intervention sessions, which were aimed to enhance skills like counting out loud. The authors classified success into four categories, including basic numeric competency, such as the ability to name numbers, and basic number comprehension, such as ‘nine is greater than three’.

The other criteria were increased number understanding (a child’s ability to add and subtract accurately) and interest in mathematics. In certain circumstances, parents were required to attend a training session to learn mathematics, which they could then apply in the games.

More than half (52%) of the activities assessed demonstrated that math skills improved significantly following the sessions with youngsters. Children in the intervention groups outperformed those who did not participate in the board game intervention in nearly a third (32%) of situations. The findings also demonstrate that, while board games in the language or literacy domains have been introduced, no scientific study (i.e. comparing control with intervention groups, or pre and post-intervention) has been conducted to assess their impact on children.

Designing and deploying board games, as well as scientific techniques to evaluate their usefulness, are thus “urgent tasks to develop in the next few years,” according to Dr. Balladares, who formerly worked at UCL. And this is the next project they’re looking into.

“Future studies should be designed to explore the effects that these games could have on other cognitive and developmental skills,” Dr. Balladares says. Given the complexity of games and the need to produce more and better games for educational purposes, an attractive field for the development of intervention and assessment of board games could open up in the coming years.”