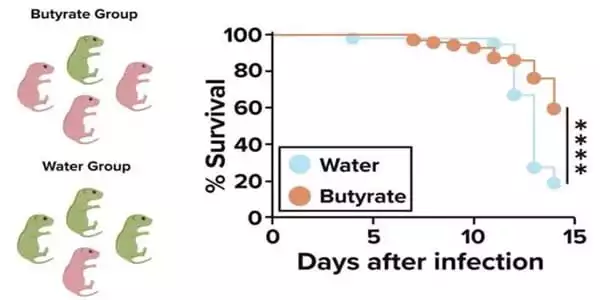

According to a new study, when pregnant mice were fed butyrate, a nutritional supplement derived from gut bacteria, majority of their pups survived an infection that causes fatal biliary atresia. Biliary atresia is a rare condition in which a delicate tree-like network of ducts that transport bile from the liver to the gut becomes damaged and obstructed. While some treatments can help to halt the progression of the disease, most infants with biliary atresia will die unless they receive a liver transplant.

However, when pregnant mice were fed butyrate, a nutritional supplement generated from gut bacteria, the majority of their pups survived after being exposed to a lethal biliary atresia infection. According to the co-authors of the current study, which was published in Nature Communications, this occurred because the moms who had the improved diet passed a healthier mix of gut bacteria to their newborns, which helped them resist the condition.

“Other studies have found that the maternal transmission of the microbiome to the newborn may alter vulnerability to later-onset diseases such as allergies, obesity, and even heart disease. Our findings suggest that this transfer has ramifications for disorders that begin in the newborn era, such as biliary atresia “According to Jorge Bezerra, MD, Director of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Cincinnati Children’s and senior author of the current study.

The disparity in survival rates was startling. When newborn mice were exposed to a virus known to cause biliary atresia, roughly 60% of those born to moms who were given butyrate survived, compared to only 20% of those delivered to mothers who were given regular food and water. The team then boosted the survival rate to as high as 83 percent when further testing indicated which substance produced by the healthier combination of gut bacteria provided the most protection.

That crucial compound was glutamine, which is also commonly available as a dietary supplement. However, rather than providing glutamine to the mothers, the researchers injected glutamine directly into the pups after birth.

According to Bezerra, the various results from different methodologies show that much more research is needed before giving any advice to human moms about what they may do to lower their children’s risk of getting biliary atresia.

Other studies have found that the maternal transmission of the microbiome to the newborn may alter vulnerability to later-onset diseases such as allergies, obesity, and even heart disease. Our findings suggest that this transfer has ramifications for disorders that begin in the newborn era, such as biliary atresia.

Jorge Bezerra

WHAT ARE BUTYRATE AND GLUTAMINE?

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that is digested by humans but is produced by our gut flora. Butyrate is produced when bacteria in our intestines break down otherwise indigestible plant fibers.

Human neonates with biliary atresia, like the mice in the study, frequently have very low levels of butyrate in their systems, which makes the favorable effects of the butyrate-rich diet worth additional examination, according to the researchers. There have been no human clinical trials of the butyrate diet to prevent biliary atresia.

In a typical human diet, glutamine is a valuable protein obtained mostly from meat and dairy products, as well as some high-protein plant sources. According to the study’s findings, glutamine directly benefits the health of bile duct tissues. It was rather surprising that the rough equivalent of a high-fiber plant diet would highlight the significance of a primarily animal-based food product.

“We believe that butyrate generation in neonates boosted the number of bacteria that produce glutamine inside the intestinal lumen,” Bezerra explains. “Both chemicals are essential, with glutamine acting as a survival factor for bile duct cells and butyrate suppressing an undesirable detrimental immunological response.” Both appear to function synergistically to reduce the risk of biliary damage.

A COMPLEX STUDY TO ANALYZE A COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP

The work, published in Nature Communications, involved building on years of previous research and utilizing multiple new and established technologies to elucidate how the interplay between our immune systems and the bacteria living in our guts might affect a rare disease. The study also included four co-lead authors and 19 other scientists from Cincinnati Children’s, the University of Cincinnati, and many Chinese institutions, in addition to Bezerra. A prior study found that mice with high levels of the bacterium Anaerococcus lactolyticus appeared to be resistant to biliary atresia. That bacterium is one of several known to produce butyrate.

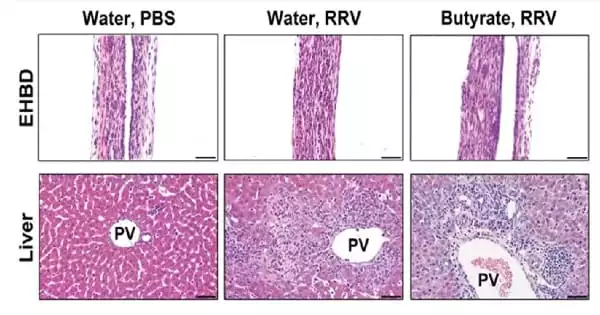

The new study used flow cytometry to investigate which types of cells inside liver tissue were influenced by butyrate, observing that the substance significantly lowered the inflammatory immune system response after pups were infected with the disease-causing virus. The researchers also utilized DNA sequencing to examine the gut bacteria community, which revealed a shared molecular signature between the maternal and newborn microbiomes when the mothers were fed butyrate.

Later, the researchers employed mass spectrometry to quantify numerous compounds produced by bacteria that may be responsible for the good effect. This study narrowed the list down to two gastrointestinal components that were significantly enhanced by the butyrate-heavy diet: hypoxanthine and glutamate.

The researchers tested both chemicals by injecting their biological cousins, inosine and glutamine, into pups with biliary atresia. Glutamine provided a significant advantage, preventing biliary atresia in 83 percent of the pups, whereas inosine had no effect. While the butyrate diet appeared to minimize a tissue-damaging immune system overreaction to the infection, glutamine specifically supported the health of bile duct epithelial cells.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR INFANTS WITH BILIARY ATRESIA?

Other than liver transplantation, there is currently no cure for biliary atresia. A surgical Kasai treatment, if performed early enough, can extend survival by restoring some of the bile flow from scar-clogged biliary trees. However, this surgery is not a cure.

If these mouse-based discoveries can be successfully translated to human disease, this discovery has the potential to change the care of many children with biliary atresia in the coming years. However, many questions remain unanswered. It is currently impossible to anticipate which neonates may develop biliary atresia, making it difficult to determine which pregnant women should consider a yet-to-be-developed supplement. While viral infections are responsible for certain occurrences of biliary atresia, the exact origin of sickness in many children is unknown.

At this time, there is no known safe dose of butyrate that is also strong enough to prevent biliary atresia. Similarly, glutamine. Much research remains to be done on the timing of any prospective treatment. Even if glutamine medication protects bile ducts against disease damage, it is unclear if glutamine can help heal damage and/or reopen existing clogged bile ducts.