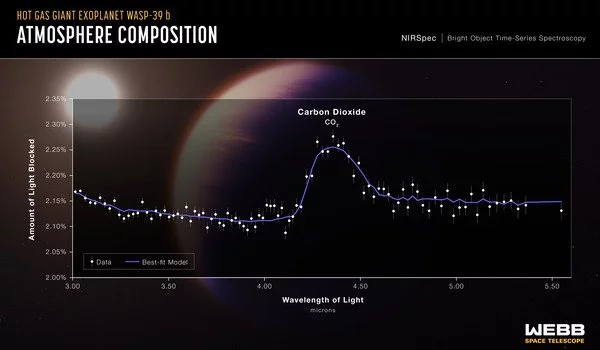

The James Webb Space Telescope has detected carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a planet in another solar system for the first time. “It’s unmistakable. It is present. “It’s definitely there,” says planetary scientist and Carnegie Institution for Science coauthor Peter Gao of Washington, D.C. “There have been hints of carbon dioxide in previous observations, but never to this extent.”

The discovery is the first detailed scientific result from the new telescope to be published. It also hints at the presence of the same greenhouse gas in the atmospheres of smaller, rockier planets similar to Earth.

WASP-39b is a massive and puffy planet. It is slightly wider than Jupiter and roughly the same size as Saturn. It also orbits its star every four Earth days, making it extremely hot. Because of these characteristics, it is a terrible place to look for evidence of extraterrestrial life. However, its puffy atmosphere and frequent passes in front of its star make it easy to observe, making it an ideal planet for putting the new telescope through its paces.

JWST, or James Webb Space Telescope, was launched in December 2021 and released its first images in July 2022. In July, the telescope observed starlight filtered through the planet’s thick atmosphere as it passed between its star and JWST for about eight hours. As it did, molecules of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere absorbed specific wavelengths of that starlight.

WASP-39b is a massive and puffy planet. It is slightly wider than Jupiter and roughly the same size as Saturn. It also orbits its star every four Earth days, making it extremely hot. Because of these characteristics, it is a terrible place to look for evidence of extraterrestrial life.

Previous observations of WASP-39b with NASA’s now-defunct Spitzer Space Telescope had detected just a whiff of absorption at that same wavelength. But it wasn’t enough to convince astronomers that carbon dioxide was really there.

“I wouldn’t have bet more than a beer, at most a six pack, on that strange tentative hint of carbon dioxide from Spitzer,” says astronomer Nicolas Cowan of McGill University in Montreal, who was not involved in the new study. He claims that the JWST detection is “rock solid.” “I wouldn’t bet my firstborn because I love him too much.” But I’d bet on a pleasant vacation.”

The JWST data also revealed an additional bit of absorption at wavelengths close to those absorbed by carbon dioxide. “It’s a mystery molecule,” says astronomer Natalie Batalha of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who led the team that made the discovery. “We’re questioning a number of suspects.”

The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of an exoplanet can reveal information about how the planet formed. Asteroids could have brought in more carbon and enriched the atmosphere with carbon dioxide if the planet was bombarded with them. If the star’s radiation stripped away some of the planet’s lighter elements, it could appear richer in carbon dioxide as well.

Despite the fact that it would require a telescope as powerful as the JWST to detect it, carbon dioxide could be present in atmospheres all over the galaxy, hiding in plain sight. “Carbon dioxide is one of the few molecules found in the atmospheres of all solar system planets with atmospheres,” says Batalha. “It’s your primary molecule.”

Astronomers hope to use JWST in the future to detect carbon dioxide and other molecules in the atmospheres of small rocky planets such as those orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1. Some of those planets, which are close enough to their star to support liquid water, could be good places to look for signs of life. It’s unclear whether JWST will detect those signs of life, but it will detect carbon dioxide.