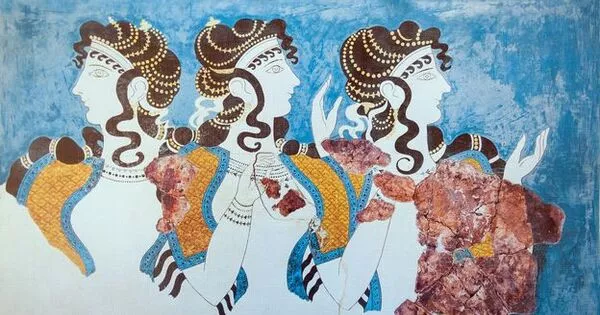

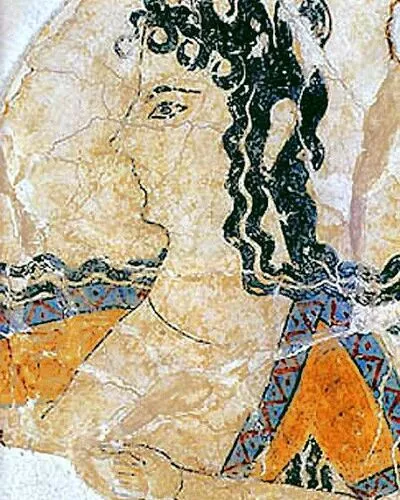

Marriage practices in Minoan Crete (a Bronze Age civilization that existed on the island of Crete from approximately 2600 to 1100 BC) are not well-documented and much of what we know is based on speculation and inference from surviving artifacts and art. However, it is believed that Minoan society was relatively egalitarian and that women enjoyed a high degree of social and economic power. It is also thought that Minoan marriages were likely arranged by families and that brides brought significant dowries to the union. Some Minoan art depicts elaborate wedding ceremonies and the participation of women in religious rituals, suggesting that marriage was an important and deeply-rooted aspect of Minoan culture.

An international team of researchers has discovered completely new information about Bronze Age marriage rules and family structures in Greece. Analyses of ancient genomes show that the choice of marriage partners was influenced by one’s own kinship.

When Heinrich Schliemann discovered the gold-rich shaft tombs of Mycenae with their famous gold masks over 100 years ago, he could only speculate about the relationship of the people buried in them. For the first time, ancient genome analysis has allowed researchers to gain insights into kinship and marriage rules in Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece. The findings were published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

A research team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA), together with an international team of partners, analysed over 100 genomes of Bronze Age people from the Aegean. “Without the great cooperation with our partners in Greece and worldwide, this would not have been possible,” says archaeologist Philipp Stockhammer, one of the study’s lead authors.

More than a thousand ancient genomes from different regions of the world have now been published, but it seems that such a strict system of kin marriage did not exist anywhere else in the ancient world. This came as a complete surprise to all of us and raises many questions.

Eirini Skourtanioti

First biological family tree of a Mycenaean family

It is now possible to produce extensive data even in regions with problematic DNA preservation due to climate conditions, such as Greece, thanks to recent methodological advances in the production and evaluation of ancient genetic datasets. It has even been possible to reconstruct the kinship of the house’s inhabitants for a Mycenaean hamlet from the 16th century BC – the first family tree that has been genetically reconstructed for the entire ancient Mediterranean region.

Some of the sons apparently remained in their parents’ hamlet as adults. At the very least, their children were buried in a tomb beneath the estate’s courtyard. One of the wives who married into the house brought her sister into the family, as her child was also buried in the same grave.

Customary to marry one’s first cousin

Marriage practices in Minoan Crete (approximately 2,700 – 1,450 BCE) are not well documented, but it is believed that they were relatively egalitarian and involved equal partnerships between spouses. Marriages were likely arranged by the families of the bride and groom and sealed with a contract or exchange of gifts. Polygamy was likely practiced by the elites in Minoan society, but monogamy was more common among the general population. There is also evidence of same-sex relationships in Minoan art, suggesting that homosexuality was accepted in Minoan society.

However, another finding was completely unexpected: on Crete and the other Greek islands, as well as on the mainland, it was very common to marry one’s first cousin 4000 years ago. “More than a thousand ancient genomes from different regions of the world have now been published, but it seems that such a strict system of kin marriage did not exist anywhere else in the ancient world,” says Eirini Skourtanioti, the lead author of the study who conducted the analyses. “This came as a complete surprise to all of us and raises many questions.”

The research team can only speculate on how this particular marriage rule can be explained. “Perhaps this was done to keep the inherited farmland from being divided up further and further? In any case, it ensured a certain continuity of the family in one location, which is essential for the cultivation of olives and wine, for example” Stockhammer is a suspect. “What is certain is that in the future, the analysis of ancient genomes will continue to provide us with fantastic, new insights into ancient family structures,” Skourtanioti adds.