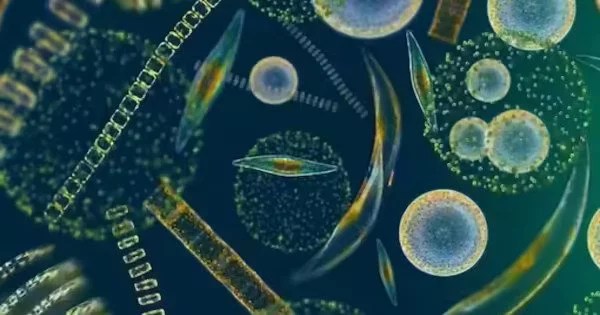

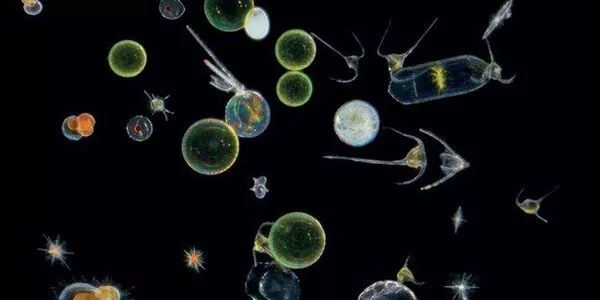

Marine plankton play an important role in the health of the ocean ecosystem and can provide insight into the overall health of the planet. Plankton are small, often microscopic, organisms that drift in the water column and are an important source of food for many larger marine species. They are also a key component of the ocean’s biogeochemical cycles, which help regulate the Earth’s climate and weather patterns.

By studying plankton, scientists can learn about the health of the ocean and the impact of human activities on the environment. Plankton are also important indicators of the overall health of the planet, as changes in plankton populations can be influenced by a variety of factors, including climate change, pollution, and overfishing.

Using samples from an almost century-old, ongoing survey of marine plankton, researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine propose that rising levels of man-made chemicals found in parts of the world’s oceans could be used to monitor the impact of human activity on ecosystem health, and could one day be used to study the links between ocean pollution and land-based rates of childhood and adult chronic illnesses.

The findings were published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

“This was a pilot study to test the feasibility of using archived samples of plankton from the Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) Survey to reconstruct historical trends in marine pollution over space and time,” said senior author Robert K. Naviaux, MD, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Medicine, Pediatrics and Pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “We were motivated to explore these new methods by the alarming increase in childhood and adult chronic disease that has occurred around the world since the 1980s.

Marine plankton exist in all ocean ecosystems. They create complex communities that form the base of the food web, and they play essential roles in maintaining the health and balance of the oceans. Plankton are generally short-lived and very sensitive to environmental changes.

Sonia Batten

“Recent research has highlighted the close relationship between ocean pollution and human health. In this study, we asked, Do changes in the plankton exposome (the sum of all exposures over a lifetime) correlate with ecosystem and fisheries health?”

We also wanted to lay the groundwork for a second question: Can human-made chemicals in plankton be used as a barometer to measure changes in the global chemosphere that may contribute to childhood and adult illness? To put it another way, we wanted to test the hypothesis that plankton’s rapid turnover and sensitivity to contamination make them a marine version of the canary in the coal mine.”

The CPR Survey, based in the United Kingdom, is the world’s longest-running and most geographically extensive marine ecology survey. Since 1931, nearly 300 ships have traveled over 7.2 million miles towing sampling devices that collect plankton and environmental data in all of the world’s oceans, the Mediterranean, Baltic, and North seas, as well as freshwater lakes.

The effort, along with other programs, is intended to document and monitor the overall health of the oceans, based on the well-being of marine plankton – a diverse collection of usually tiny organisms that provide food for many other aquatic creatures, ranging from mollusks to fish to whales.

“Marine plankton exists in all ocean ecosystems,” said study co-author Sonia Batten, Ph.D., former coordinator of the Pacific CPR and currently executive secretary of the North Pacific Marine Science Organization. “They create complex communities that form the base of the food web, and they play essential roles in maintaining the health and balance of the oceans. Plankton is generally short-lived and very sensitive to environmental changes.”

Naviaux, co-corresponding author Kefeng Li, Ph.D., a project scientist in Naviaux’s lab, and colleagues assessed plankton specimens taken from three different locations in the North Pacific at different times between 2002 and 2020, then used a variety of technologies to assess their exposure to various humanmade chemicals, including pharmaceuticals; persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as industrial chemicals; pesticides; phthalates and plasticizers (chemicals deriving from plastics).

Many of these pollutants have decreased in amount over the past two decades, the researchers said, but not universally, and often in complex ways. For example, analyses suggest levels of legacy POPs and the common antibiotic amoxicillin have broadly declined in the North Pacific Ocean over the past 20 years, perhaps in part from increased federal regulation and a decrease in overall antibiotic use in the United States and Canada, but the findings are confounded by coinciding increases in use in Russia and China.

The most polluted samples were collected from nearshore areas that were subject to phenomena such as terrestrial runoff and aquaculture. Higher levels and greater numbers of different chemicals were found in plankton taxa living in these nearshore environments.

According to the authors, their pilot project paves the way for future research into correlations between the plankton exposome, predator-prey relationships, and impacted fisheries. “Follow-up studies by epidemiologists and marine ecologists are needed to test if and how the plankton exposome correlates with important medical trends in nearby human populations like infant mortality, autism, asthma, diabetes, and dementia,” Naviaux said.

The findings, according to Naviaux, provide new insights into the nature of many chronic diseases in which phases of the cell danger response (CDR) persist, resulting in chronic symptoms. For more than a decade, Naviaux and colleagues have argued that mounting evidence suggests that a wide range of diseases and chronic illnesses, from neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorder and neurodegenerative disorders like ALS to cancer and major depression, are at least partly the result of metabolic dysfunction that results in incomplete healing, a condition known as CDR.

Naviaux has published extensively on the topic, including how CDR can be affected by environmental factors that result in metabolic dysfunction and chronic disease.

“The purpose of CDR is to help protect the cell and jump-start the healing process following injury by causing the cell to harden its membranes, decrease and change its interaction with neighbors, and redirect energy and resources for defense until the danger has passed,” Naviaux explained.

“However, the CDR occasionally becomes stuck. This prevents the natural healing cycle from being completed, altering the way the cell responds to the outside world. When this occurs, cells act as if they are still injured or in imminent danger, despite the fact that the original cause of the injury or threat has passed. Many types of environmental chemicals, trauma, infection, and other types of stress have been shown to delay or obstruct the healing cycle. When this happens, it leads to the symptoms of chronic disease.”

“The CDR is a whole-body process that begins with mitochondria and the cell. Mitochondria are organelles in the cell that act as bio-sentinels that are constantly monitoring the chemistry of the cell and its surroundings. Mitochondria regulate metabolic activity needed for energy and movement, innate immunity, for regulating the health of the microbiome, and for making the building blocks needed for tissue repair after injury.”

Naviaux and colleagues discovered that perfluoroalkyl substances (chemicals commonly used to improve water resistance in a variety of everyday products ranging from packaging to clothing to cookware) were prevalent in the plankton exposome in their marine plankton study.

Some mitochondrial proteins, including an important enzyme used to regulate cortisol metabolism and organisms’ responses to stress, are known to be inhibited by such substances. Phthalates from plastics and personal care products, such as lotions and shampoos, were also discovered. Phthalates are endocrine disruptors that have been increasing in the plankton exposome for over 20 years and have both direct and indirect effects on mitochondria.