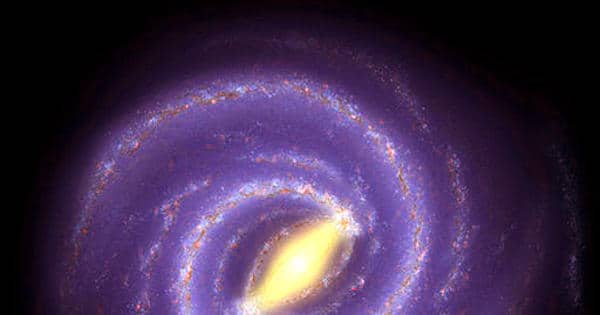

The research found Milky Way galaxy is surrounded by a clumpy halo

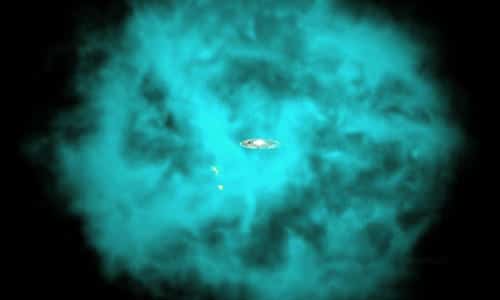

Our Milky Way is surrounded by a “clumpy halo” that could be hiding mysterious missing matter, astronomers have said. University of Iowa astronomers have determined our galaxy is surrounded by a clumpy halo of hot gases that are continually being supplied with material ejected by birthing or dying stars. The galaxy is wrapped in a ring of hot gases that are constantly being topped up as stars are born and die, scientists say. This heated halo, called the circumgalactic medium (CGM), was the incubator for the Milky Way’s formation some 10 billion years ago and could be where basic matter unaccounted for since the birth of the universe may reside. And inside that halo could be a basic matter that has been missing since the birth of the universe, researchers say.

The findings come from observations made by HaloSat, one of a class of minisatellites designed and built at Iowa — this one primed to look at the X-rays emitted by the CGM. Researchers built the spacecraft to look for X-rays being sent out by the CGM, in an attempt to better understand it, its behavior, and shape. The researchers conclude the CGM has a disk-like geometry, based on the intensity of X-ray emissions coming from it. The HaloSat minisatellite was launched from the International Space Station in May 2018 and is the first minisatellite funded by NASA’s Astrophysics Division. All galaxies have their own CGM, and understanding how they operate is key to explaining not just how the galaxies formed but how they could become the busy mix of stars, planets, and other objects that we live in today.

“Where the Milky Way is forming stars more vigorously, there are more X-ray emissions from the circumgalactic medium,” says Philip Kaaret, a professor in the Iowa Department of Physics and Astronomy and corresponding author on the study, published online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The chief aim of HaloSat was to look for baryonic matter, atomic remnants that are believed to have been missing since the universe was born almost 14 billion years ago. Each galaxy has a CGM, and these regions are crucial to understanding not only how galaxies formed and evolved but also how the universe progressed from a kernel of helium and hydrogen to a cosmological expanse teeming with stars, planets, comets, and all other sorts of celestial constituents. Researchers think that matter could be hiding in the CGM and that examining it could help them find that long lost matter.

HaloSat was launched into space in 2018 to search for atomic remnants called baryonic matter believed to be missing since the universe’s birth nearly 14 billion years ago. The satellite has been observing the Milky Way’s CGM for evidence the leftover baryonic matter may reside there.

Milky Way’s Halo is Disk-Like and Clumpy

More specifically, the researchers wanted to find out if the CGM is a huge, extended halo that is many times the size of our galaxy — in which case, it could house the total number of atoms to solve the missing baryon question. But if the CGM is mostly comprised of recycled material, it would be a relatively thin, puffy layer of gas and an unlikely host of the missing baryonic matter.

“What we’ve done is definitely show that there’s a high-density part of the CGM that’s bright in X-rays, that makes lots of X-ray emissions,” Kaaret says. “But there still could be a really big, extended halo that is just dim in X-rays. And it might be harder to see that dim, extended halo because there’s this bright emission disc in the way.

“So it turns out with HaloSat alone, we really can’t say whether or not there really is this extended halo.”

“It seems as if the Milky Way and other galaxies are not closed systems,” Kaaret says. “They’re actually interacting, throwing material out to the CGM, and bringing back material as well.”

The next step is to combine the HaloSat data with data from other X-ray observatories to determine whether there’s an extended halo surrounding the Milky Way and if it’s there, to calculate its size. That, in turn, could solve the missing baryon puzzle.

“Those missing baryons better be somewhere,” Kaaret says. “They’re in halos around individual galaxies like our Milky Way or they’re located in filaments that stretch between galaxies.”

In the future, scientists will combine the HaloSat data with data from other X-ray observatories to determine whether there’s an extended halo surrounding the Milky Way and if it’s there, to calculate its size. That, in turn, could solve the missing baryon puzzle.