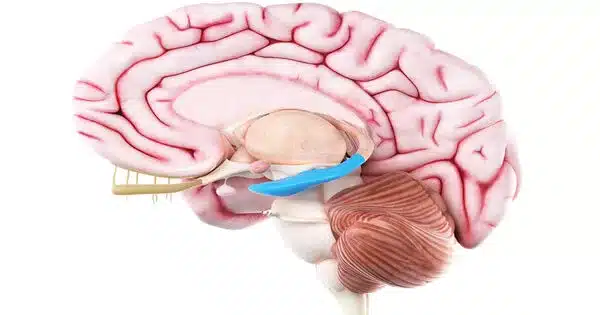

Deep-brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical procedure in which electrodes are implanted in specific areas of the brain and electrical impulses are delivered through these electrodes. DBS has been used to treat a variety of medical conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, and dystonia.

The first physiological evidence from inside the human brain supporting the dominant scientific theory on how the brain consolidates memory during sleep has been discovered in new research. Deep-brain stimulation also appeared to improve memory consolidation during a critical time in the sleep cycle.

While it is well known that sleep plays an important role in memory consolidation, scientists are still trying to figure out how this process occurs in the brain overnight.

A new study led by UCLA Health and Tel Aviv University scientists provides the first physiological evidence from inside the human brain to support the dominant scientific theory on how the brain consolidates memory during sleep. Furthermore, the researchers discovered that targeted deep-brain stimulation during a critical time in the sleep cycle improved memory consolidation.

This provides the first major evidence down to the level of single neurons that there is indeed this mechanism of interaction between the memory hub and the entire cortex. It has both scientific value in terms of understanding how memory works in humans and using that knowledge to really boost memory.

Itzhak Fried

According to study co-author Itzhak Fried, MD, PhD, the findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, could provide new insights into how deep-brain stimulation during sleep could one day help patients with memory disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. This was accomplished through the use of a novel “closed-loop” system that delivered electrical pulses precisely synchronized to brain activity recorded from another region.

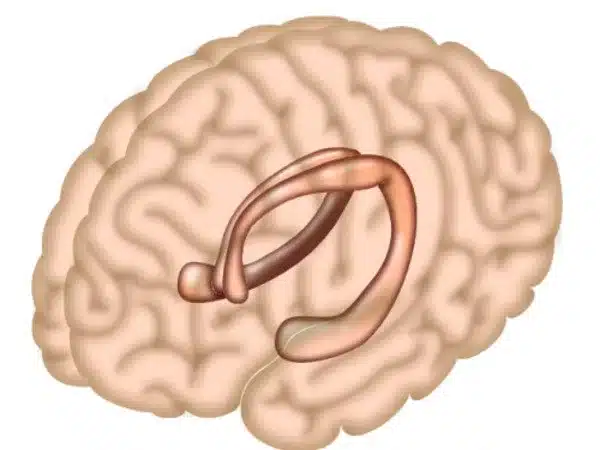

The dominant theory for how the brain converts new information into long-term memories during sleep involves an overnight dialogue between the hippocampus, the brain’s memory hub, and the cerebral cortex, which is associated with higher brain functions such as reasoning and planning. This happens during a deep sleep phase when brain waves are particularly slow and neurons across brain regions alternate between rapidly firing in sync and silence.

“This provides the first major evidence down to the level of single neurons that there is indeed this mechanism of interaction between the memory hub and the entire cortex,” said Fried, the director of epilepsy surgery at UCLA Health and professor of neurosurgery, psychiatry, and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “It has both scientific value in terms of understanding how memory works in humans and using that knowledge to really boost memory.”

The researchers had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to test this theory of memory consolidation in the brains of 18 epileptic patients at UCLA Health. The electrodes were implanted in the patients’ brains to help identify the source of their seizures during 10-day hospital stays.

The research was carried out over two nights and mornings. Just before going to bed, study participants were shown photos of animals and 25 celebrities, including well-known names like Marilyn Monroe and Jack Nicholson. They were tested right away to see if they could remember which celebrity was paired with which animal, and they were tested again the next morning after a night of uninterrupted sleep.

On another night, they were shown 25 new animal and celebrity pairings before bedtime. This time, they received targeted electrical stimulation overnight, and their ability recall the pairings was tested in the morning. To deliver this electrical stimulation, the researchers had created a real-time closed-loop system that Fried likened to a musical conductor: The system “listened” to brain’s electrical signals, and when patients fell into the period of deep sleep associated with memory consolidation, it delivered gentle electrical pulses instructing the rapidly firing neurons to “play” in sync.

When compared to a night of undisturbed sleep, each individual tested performed better on memory tests after a night of sleep with electrical stimulation. Key electrophysiological markers also showed that information was flowing between the hippocampus and the cortex, providing physical evidence for memory consolidation.

“We discovered that we essentially improved this highway by which information flows to more permanent storage places in the brain,” Fried explained.