Boys with autism have very repetitive and confined play spaces. Girls with autism are less repetitive and have a larger range of play activities. Girls with autism are more likely than boys to respond to nonverbal communication techniques such as pointing or gaze following.

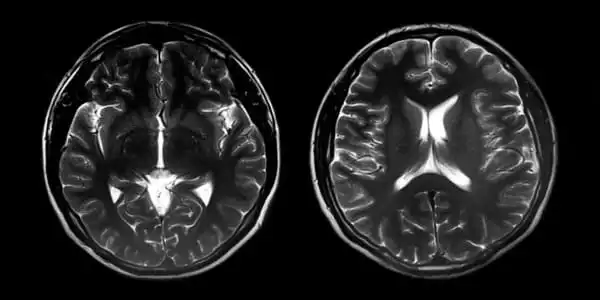

A new study using artificial intelligence discovers that girls with autism differ in several brain areas from boys with autism, implying that gender-specific diagnostics are required. According to a new study from Stanford University School of Medicine, brain organization differs between boys and girls with autism.

The differences, which were discovered by analyzing hundreds of brain scans using artificial intelligence tools, were specific to autism and not observed in typically developing boys and girls. According to the researchers, the study helps explain why autism symptoms differ between sexes and may pave the road for better diagnosis for girls.

Autism is a developmental disease that has a range of severity. Affected children exhibit social and communication difficulties, as well as limited interests and repetitive activities. Leo Kanner, MD, provided the first description of autism in 1943, and it was skewed toward male patients. Autism affects four times as many boys as females, and most autism research has concentrated on males.

We found significant variations in the brains of boys and girls with autism, and we were able to predict clinical symptoms in girls. We know that symptom camouflage is a significant barrier in the identification of autism in girls, resulting in diagnostic and treatment delays.

Professor Vinod Menon

“When a problem is characterized in a biased way, diagnostic methods are biased,” said lead author Kaustubh Supekar, Ph.D., a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “This research shows that we need to think differently.”

The study was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry online.

“We found significant variations in the brains of boys and girls with autism, and we were able to predict clinical symptoms in girls,” said the study’s principal author, Vinod Menon, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the Rachael L. and Walter F. Nichols, MD, Professor. “We know that symptom camouflage is a significant barrier in the identification of autism in girls, resulting in diagnostic and treatment delays.”

According to the study, girls with autism had fewer overt repetitive behaviors than boys, which may contribute to diagnostic delays.

“Knowing that males and females do not present in the same way, both behaviorally and neurologically, is really persuasive,” said Lawrence Fung, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and not a research author.

At Stanford Children’s Health, Fung treats people with autism, including girls and women with delayed diagnosis. Many autism treatments, he says, are most effective during the preschool years, when the brain’s movement and language centers are growing.

“If the treatments can be done at the proper time, it makes a huge difference: for example, children on the autism spectrum who receive early language intervention have a greater chance of learning language like everyone else and won’t have to play catch-up as they grow older,” Fung added. “When a child is unable to express herself well, they lag behind in a variety of areas. If they do not receive early diagnosis, the consequences are severe.”

New statistical methods unlock differences

The researchers examined functional magnetic resonance imaging brain scans from 773 autistic children, 637 boys and 136 girls. Obtaining enough data to include a significant number of girls in the study was difficult, according to Supekar, who noted that the small number of females traditionally included in autism research has been a barrier to understanding more about them. The team relied on data gathered at Stanford as well as public databases comprising brain scans from research facilities throughout the world.

The predominance of boys in brain-scan databases created a mathematical challenge: To discover differences across groups, most statistical approaches require that the groups be about equal in size. These methodologies, which underpin machine-learning techniques in which algorithms may be trained to detect patterns in very vast and complicated datasets, are insufficient for a real-world situation in which one group is four times larger than the other.

“When I tried to find distinctions [using standard methods], the algorithm would tell me that every brain is a male with autism,” Supekar explained. “It was overlearning and failing to differentiate between males and females with autism.”

Supekar discussed the issue with Tengyu Ma, PhD, an assistant professor of computer science and statistics at Stanford and a study co-author. Ma had recently devised a method for comparing complicated datasets from different-sized groups, such as brain scans. The new technique offered the essential breakthrough for the scientists.

“We happened to be lucky that this new statistical approach was developed at Stanford,” Supekar said.

What differed?

The researchers built an algorithm that could discriminate between boys and girls with 86 percent accuracy using 678 brain scans from children with autism. When scientists tested the system on the remaining 95 brain scans from autistic children, it retained the same accuracy in differentiating between boys and girls.

The method was also evaluated on 976 brain images from typically developing boys and girls. The computer was unable to discriminate between them, confirming that the sex differences discovered by the investigators were unique to autism.

Girls displayed distinct patterns of connection than males in various brain areas, including motor, language, and visuospatial attention systems, in autistic children. The differences between sexes were greatest in a set of motor areas, including the primary motor cortex, supplementary motor area, parietal and lateral occipital cortex, and middle and superior temporal gyri. The severity of motor symptoms was connected to differences in motor centers among females with autism, implying that girls whose brain patterns were most similar to boys with autism tended to have the most pronounced motor symptoms.

The researchers also discovered linguistic areas that differed between boys and girls with autism, noting that previous studies had found larger language abnormalities in boys. “When you find that there are changes in regions of the brain that are associated to clinical symptoms of autism, this looks more real,” Supekar said.

The data, taken collectively, should be used to guide future efforts to enhance diagnosis and treatment for females, according to the researchers. “Our research extends the application of artificial intelligence-based approaches for precision psychiatry in autism,” Menon added.

“We may require different tests for females than for guys. Our artificial intelligence techniques may aid in the identification of autism in girls “Supekar explained. Interventions for girls might be undertaken sooner at the treatment level, he noted.