A diet rich in whole foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats, and lean protein, may help prevent cancer. Processed meats, refined carbohydrates, salt, and alcohol, on the other hand, may raise your risk. Although no diet has been proven to cure cancer, plant-based and keto diets may reduce your risk or improve treatment.

Researchers studied ketogenic and calorically restricted diets in mice, revealing how these diets affect cancer cells and providing an explanation for why calorie restriction may slow tumor growth.

There has been some evidence in recent years that dietary interventions can help to slow the growth of tumors. A new MIT study that looked at two different diets in mice reveals how those diets affect cancer cells and provides an explanation for why calorie restriction may slow tumor growth.

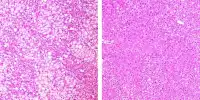

The researchers looked at how a calorically restricted diet and a ketogenic diet affected mice with pancreatic tumors. While both of these diets reduce the amount of sugar available to tumors, the researchers discovered that only the calorically restricted diet reduced the availability of fatty acids, which was associated with a slowing of tumor growth.

We studied ketogenic and calorically restricted diets in mice, revealing how these diets affect cancer cells and providing an explanation for why calorie restriction may slow tumor growth.

Matthew Vander Heiden

According to the researchers, the findings do not imply that cancer patients should try to follow either of these diets. Instead, they believe the findings call for more research into how dietary interventions can be combined with existing or emerging drugs to help cancer patients.

“There’s a lot of evidence that diet can affect how quickly your cancer progresses, but this isn’t a cure,” says Matthew Vander Heiden, senior author of the study and director of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. “While the findings are intriguing, more research is required, and individual patients should consult with their doctor about the best dietary interventions for their cancer.”

MIT postdoc Evan Lien is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature.

Metabolic mechanism

Vander Heiden, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, says his patients frequently ask him about the potential benefits of different diets, but there isn’t enough scientific evidence to provide definitive advice. Many patients’ dietary concerns center on either a calorie-restricted diet, which reduces calorie consumption by 25 to 50 percent, or a ketogenic diet, which is low in carbohydrates and high in fat and protein.

Previous research has suggested that a calorically restricted diet may slow tumor growth in some circumstances, and such a diet has been shown to increase lifespan in mice and many other animal species. A smaller number of studies on the effects of a ketogenic diet on cancer yielded inconclusive results.

“A lot of the advice or cultural fads out there aren’t always based on very good science,” Lien explains. “It seemed like there was an opportunity, especially given how much our understanding of cancer metabolism has evolved over the last decade or so, to apply some of the biochemical principles that we’ve learned to understanding this complex question.”

Because cancer cells consume a lot of glucose, some researchers hypothesized that the ketogenic diet or calorie restriction would slow tumor growth by reducing the amount of glucose available. However, the MIT team’s initial experiments in mice with pancreatic tumors revealed that calorie restriction has a much greater effect on tumor growth than the ketogenic diet, raising the possibility that glucose levels were not playing a significant role in the slowdown.

To delve deeper into the mechanism, the researchers examined tumor growth and nutrient concentration in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice fed a normal, ketogenic, or calorie-restricted diet. Glucose levels decreased in both ketogenic and calorie-restricted mice. Lipid levels decreased in the calorie-restricted mice, but increased in the ketogenic diet mice.

Lipid deficiency inhibits tumor growth because cancer cells require lipids to build their cell membranes. When lipids aren’t available in a tissue, cells can synthesize their own. As part of this process, they must maintain the proper balance of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, which necessitates the use of an enzyme known as stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD). This enzyme is in charge of converting saturated fatty acids to unsaturated fatty acids.

SCD activity is reduced by both calorie-restricted and ketogenic diets, but mice on the ketogenic diet had lipids available to them from their diet, so they didn’t need to use SCD. Mice on a calorie-restricted diet, on the other hand, were unable to obtain fatty acids from their diet or produce their own. When compared to mice fed a ketogenic diet, tumor growth was significantly slowed in these mice.

“Caloric restriction not only deprives tumors of lipids, but it also impairs the process that allows them to adapt to it. This combination has a significant impact on tumor growth inhibition “According to Lien.

Dietary effects

In addition to their mouse studies, the researchers examined some human data. The team obtained data from a large cohort study, which allowed them to analyze the relationship between dietary patterns and survival times in pancreatic cancer patients, with the help of Brian Wolpin, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and one of the paper’s authors. According to the findings of that study, the type of fat consumed appears to influence how patients on a low-sugar diet fare after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis, though the data is insufficient to draw any conclusions about the effect of diet, the researchers say.

Although this study found that calorie restriction is beneficial in mice, the researchers do not recommend that cancer patients follow a calorie-restricted diet because it is difficult to maintain and can have negative side effects. They believe, however, that cancer cells’ reliance on the availability of unsaturated fatty acids could be used to develop drugs that could help slow tumor growth.

Inhibiting the SCD enzyme, which prevents tumor cells from producing unsaturated fatty acids, could be one possible therapeutic strategy. “The goal of these studies isn’t necessarily to recommend a diet, but rather to truly understand the underlying biology,” Lien explains. “They give us a sense of how these diets work, and that can lead to rational ideas about how we might mimic those situations for cancer therapy.”

The researchers will now investigate how diets containing a variety of fat sources, such as plant or animal fats with defined differences in saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acid content, affect tumor fatty acid metabolism and the unsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio.