The Dutch ship Batavia sunk on its maiden trip about 400 years ago. Scientists have now investigated the rings in the ship’s wood to solve a 17th-century construction conundrum. To do so, they had to develop new wood sample procedures, which took 15 years to design and implement, but their approach might utilized to solve other historical puzzles. Despite being smaller and lacking in resources than its competitors, the Netherlands grew into a significant maritime power with colonies spanning the Americas and Southeast Asia. Some of the factors that contributed to their success, like their early use of wind power are well known to historians, while others remain a mystery.

Dr. Wendy van Duivenvoorde of Flinders University, a shipwreck detective, led the team that exploited the fate of one of the less successful Dutch ships to solve one riddle in PLOS 1. The conquering of the world by Europe required ships that could not be built out of any old wood. It was critical to have access to adequate wood. The Netherlands did not have enough wood to build the 706 ships the Dutch East India Company built in the 17th century, leaving historians puzzled as to where the wood came from.

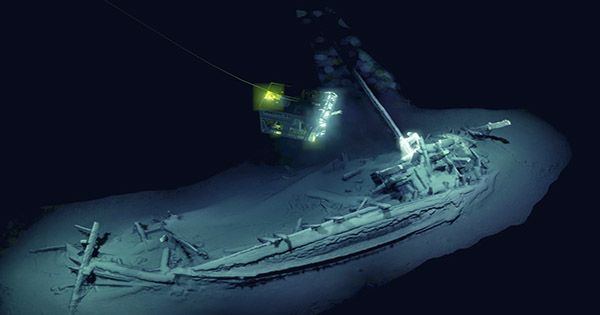

“We know the Netherlands had a market for timber from throughout Europe,” Van Duivenvoorde told IFLScience, “but the auction records don’t start until approximately 1650.” “A lot of records before then are missing from national archives,” van Duivenvoorde told IFLScience. Sailing was a risky business at the time, and the Batavia, the Company’s ship, sunk off Australia’s Morning Reef on its route to the town that bears its name (now called Jakarta). Parts were recovered and displayed at Fremantle’s Shipwrecks Museum in the 1970s. Van Duivenvoorde and his co-authors understood this was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to analyze and identify the wood used in the construction of Dutch ships.

Van Duivenvoorde told IFLScience that wood was the chosen material for shipbuilding. “This was fine-grained slow-growing oak below the waterline.” This was discovered in the Baltic area, where trees grow straighter, making the wood easier to work with.” The frames of the Batavia were made of twisted oak from Lower Saxony. In other areas, pine employed, the origins of which are unknown. In a statement, first author Dr. Aoife Daly of the University of Copenhagen said, “The preference for certain timber products from designated places suggests that the choice of lumber was far from arbitrary.”

Identifying the sources of Batavia’s wood presented two obstacles, according to Van Duivenvoorde. The first is that wood that has spent centuries underwater is generally in such bad condition that taking the cores required is impracticable, excluding most Dutch East India Company ships from research even when their last resting place is known. Even with the Batavia on land, it took years for the team to figure out how to keep the wood safe while collecting cores.

After doing this, the researchers analyzed databases of tree rings taken from oaks of known provenance that had been utilized for construction. These rings have been intensively investigated because they provide a record of Europe’s climate throughout the last millennium, revealing how unusual the previous 50 years have been.

The database created because of the process was an invaluable resource for paper writers who were able to find the exact sequence of good and bad growth that matched each part of Batavia to identify the wood that came from the forest, as well as the years in which it grew. A few years of growth moved for greater resilience. Getting the timber was just half of the battle for the shipbuilders. The Dutch were able to build the world’s biggest maritime fleet because to the usage of wind-powered sawmills and improved hull construction.