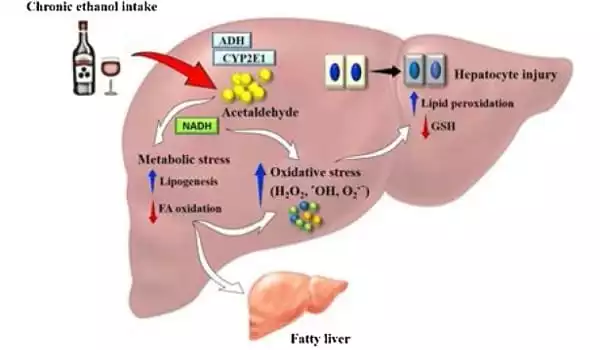

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and liver-related mortality, both of which are caused by acute or chronic alcohol intake, are among the global healthcare costs. Chronic alcohol intake harms the liver’s regular defensive mechanisms and is likely to disrupt the gut barrier system and mucosal immune cells, resulting in reduced nutritional absorption.

The treatment of ALD is dependent on the severity of the liver impairment that causes fatty liver, hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Abstaining from alcohol is the foundation of therapy. Corticosteroids are used to treat ALD, but due to poor acceptance, ongoing mortality, and the discovery of tumor necrosis factor-alpha as an integral component in pathogenesis, recent studies have focused on pentoxifylline and antitumor necrosis factor antibodies to neutralize cytokines in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Researchers have discovered a novel mechanism that helps explain how excessive alcohol use promotes liver damage, specifically mitochondrial dysfunction in alcohol-associated liver disease.

Cedars-Sinai researchers discovered a new mechanism that helps explain how excessive alcohol use promotes liver damage, specifically mitochondrial dysfunction in alcohol-associated liver disease. The study, which was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications, may also lead to a novel therapy method for those suffering from the disease.

Alcohol-related liver disease is a serious problem around the world. We’ve known for a long time that alcohol damages mitochondria, but the methods by which this damage occurs were unknown until recently.

Shelly C. Lu

Cases of alcohol-related liver disease are on the rise, and it is one of the primary causes of alcohol-related mortality. The disease’s symptoms range from hepatitis to fibrosis to cirrhosis and liver cancer. Cirrhosis alone is responsible for 1.6 million fatalities worldwide, with alcohol misuse accounting for more than half of all cases. Aside from abstinence, there are presently no viable medicines for treating patients with the illness.

“Alcohol-related liver disease is a serious problem around the world,” said Shelly C. Lu, MD, senior author of the study and director of the Karsh Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Department of Medicine. “We’ve known for a long time that alcohol damages mitochondria, but the methods by which this damage occurs were unknown until recently.”

The liver contains a high concentration of mitochondria, which are known as the powerhouses of all cells and play an important role in liver function. Alcohol, on the other hand, can affect the structure and function of the mitochondria, resulting in liver damage.

Lu and her colleagues investigated the role of an enzyme called MAT?1 in providing the liver with necessary nutrients for survival in order to better understand the causes underlying mitochondrial damage in alcohol-associated liver disease.

The scientists discovered that levels of this enzyme were preferentially lowered in the mitochondria using liver tissues from individuals with alcohol-related liver disease and preclinical models. “Once we identified the MAT?1 depletion, we needed to figure out what was causing it,” said Lucia Barbier-Torres, PhD, a postdoctoral investigator in the Lu Laboratory and the study’s first author.

The researchers discovered that alcohol activates the casein kinase 2 (CK2) protein, which initiates a process known as phosphorylation of MAT?1 at a specific amino acid position. The scientists discovered that this pathway enables an interaction between MAT?1 and another protein called PIN1 and hinders MAT?1 from trafficking into the mitochondria.

“Once this interaction occurs, MAT?1 cannot enter the mitochondria to give the required nutrition and instead degrades,” Barbier-Torres explained.

With this knowledge, the scientists decided to obstruct this connection by mutating MAT?1, hence blocking phosphorylation. This prevented the two proteins from interacting, conserving mitochondrial MAT?1 position and function, and so protecting the mitochondria from damage caused by alcohol use. When they reduced CK2 expression to lower MAT?1 phosphorylation, they found the same level of protection.

The therapy aspects must restore gastrointestinal processes and necessitate nutrient-based treatments to regulate gut functions and prevent liver harm. Saturated fatty acids play an important role in controlling the intestinal barrier. Overall, this review focuses on the mechanism of alcohol-induced metabolic dysfunction, the role of pregnancy in liver etiology, and targeted ALD therapy.

“Our findings support an unique and targetable mechanism to aid in the treatment of alcohol-related liver illness,” said Lu, a professor of Medicine and the Women’s Guild Chair in Gastroenterology.

The next step in this line of study for Lu and her colleagues is to create small molecule therapies that can disrupt the link between MAT?1 and PIN1, so protecting the mitochondria from alcohol-mediated harm.