A Bronze Age donkey-ass hybrid Mesopotamia is the first known example of a human-bred hybrid animal. The horse-like creatures’ bones date back 4,500 years, putting an end to decades of speculation about the ancient equids’ identities. The Institut Jacques Monod (CNRS/Université de Paris) believes the bones belong to a kunga — a hybrid between a female domestic donkey and a male wild ass – after thorough DNA sequencing. Their findings have been reported in Science Advances.

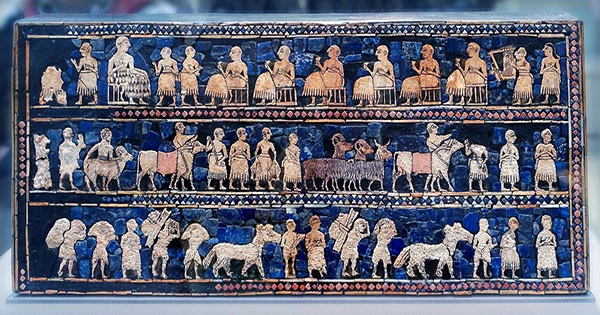

In 2006, the bones of 25 animals were unearthed in Tell Umm el-Marra, a royal mausoleum in northern Syria. They later identified as kungas. The whole skeletons resembled horses, but their proportions were off, perplexing archaeologists, as was the fact that horses were not introduced to the area until 500 years later. The mysterious equids can also be found in Mesopotamian writings and symbols, where they are described as utilized in “diplomacy, ritual, and combat.” Larger Kung as used to draw cars, whereas smaller kungas are employed in agriculture, such as hauling ploughs.

However, it was not until the researchers matched their genomes to those of other species that they were able to figure out what these strange creatures were, because the skeletons did not belong to horses, asses, or onagers (Asian wild asses), the researchers speculated that they might be a hybrid. To prove it, they sequenced DNA from an 11,000-year-old equid bone discovered in Turkey, as well as teeth and hair from the last-surviving Syrian wild asses from the 19th century. The skeletons discovered in Syria had the mother lineage of a domestic donkey (E. africanus) and the paternal lineage of a Syrian wild assyrian (E. hemionus).

This blend, according to researchers, may have offered the ideal balance of donkey temperament and wild ass speed. The resulting kunga would have been more readily tamed than an ass, but stronger and faster than a donkey. They were also supposed to be six times the price of a donkey, a clever little idea from an early Syro-Mesopotamian culture that evidently knew a lot about breeding.

“It’s surprising to see that these ancient societies envisioned something as complex as hybrid breeding,” co-author Eva-Maria Geigl told Gizmodo, “because this was an intentional act: they had the domestic donkey, they knew they couldn’t domesticate the Syrian wild ass, and they didn’t domesticate horses.” “As a result, they established a purposeful breeding technique to blend diverse features that they deemed desirable in each of the parent species.”

This was no small effort, as hybrid creatures, such as the sturddlefish and whaluga, are usually (but not always) sterile, implying that each kunga purposefully breed into existence. The added trouble may have contributed to the kanga’s final extinction. Mesopotamian societies had a similar strong and quick animal to use until the domestic horse arrived 4,000 years ago, and it was much easier to reproduce.