A team of university psychologists shows that when focusing their attention, infants under a year of age recruit areas of their frontal cortex, a section of the brain involved in more advanced functions that were previously thought to be immature in babies, using an approach that uses fMRI (or functional magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the brains of awake babies.

Anyone who has seen an infant’s eyes follows a dangling trinket dancing in front of them knows that babies have laser-like focus. But how do they do it with large areas of their young brains still underdeveloped?

A team of university psychologists shows that when focusing their attention, infants under a year of age recruit areas of their frontal cortex, a section of the brain involved in more advanced functions that were previously thought to be immature in babies, using an approach pioneered at Yale that uses fMRI (or functional magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the brains of awake babies. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

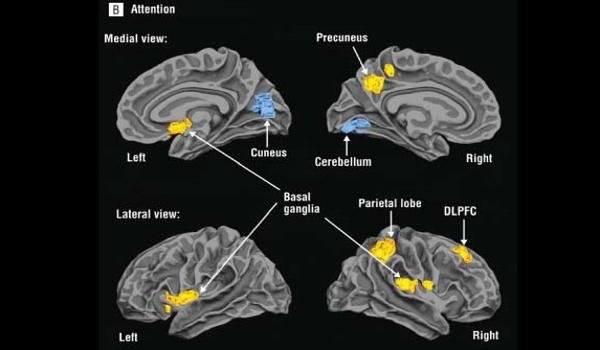

Neuroimaging reveals when babies focus their attention, they utilize areas of the frontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with more advanced functions and previously believed to be immature in children under a year of age.

“Attention is the gateway to what infants perceive and learn,” said Nick Turk-Browne, a Yale professor of psychology and the paper’s senior author. “Attention is the doorman, determining what information enters the brain and eventually creates memories, language, and thought.”

The majority of previous attention research in babies has relied on tracking their gaze while they are presented with visual stimuli, a process that theoretically provides insights into what is going on in their minds. Questions remain unanswered about which parts of the brain are involved in these responses, as well as how and why they allocate attention in these ways.

Babies’ attention may be dependent on sensory areas of the brain, which process stimuli such as touch and visual stimuli and help them react to the outside world. These brain regions develop earlier in childhood than frontal cortex regions, which are typically associated with internal functions like control, planning, and reasoning.

The ability to use brain imaging with infants allowed Turk-Browne to “look behind the mirror” for the neural origins of attention. They used the new fMRI technology to track the neural activity of 20 babies ranging in age from 3 to 12 months, determining which regions of their brains were activated as they focused their attention on a series of images.

The babies were shown a screen with a target on either the left or right side in a series of tests. These appearances were preceded in each case by one of three visual cues indicating where the target would appear: on the same side as the target, on both sides of the screen (thus uninformative), or on the opposite side. The researchers observed the babies’ eye movements as they performed these tasks.

When the babies were first shown the correct cue, they moved their eyes to the target much faster than expected, confirming that the cues had focused their attention. Concurrently, the researchers used brain imaging technology to determine which areas of the brain were activated during these tasks. In addition to sensory areas of the brain, they discovered that activity increased in two areas of the frontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the middle frontal gyrus, which are involved in controlling adult attention when fully developed.

“This doesn’t mean these regions play the same role in babies as they do in adults, but it does show that infants use them to explore their visual world,” said Cameron Ellis, the paper’s first author and a Ph.D. candidate in psychology at Yale.

“Understanding the foundations of human learning will help researchers uncover the foundations of human learning, which could one day help improve early-childhood education and reveal the roots of neurodevelopmental disorders,” Ellis said.