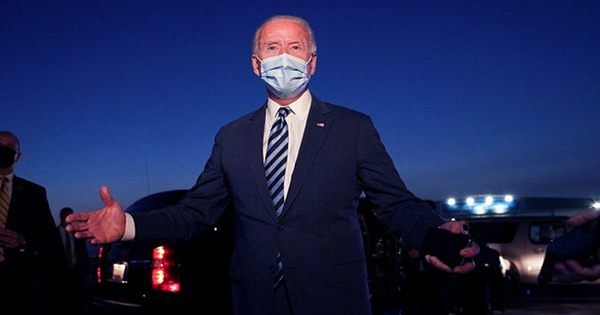

In July, President Joe Biden signed an executive order aimed at “enhancing competition” in the United States’ economy. “Today, a tiny number of dominant Internet platforms utilize their dominance to block market entrants, to earn monopolistic profits, and to amass intimate personal information that they may use for their own advantage,” the ruling says. The US Senate sponsored a bill in November aimed at preventing anti-competitive mergers and acquisitions among digital corporations.

In the United States, there has not been a serious monopolization case in 20 years, but the present government appears to be interested in making one stick. To date, there is still too much gray space in the regulations and reluctance among people to enforce antitrust legislation, but strong intentions might lead to the new policy, penalties, and even prosecution with a few tweaks to the strategy. Antitrust regulation has lost its fangs over the previous century, and its broad aims have been replaced with a hazy norm centered on “consumer welfare.” During the 1980s, the acid test for antitrust was whether suspected antitrust measures resulted in higher consumer costs.

This attempt to reduce antitrust to a single economic test has been found to be unnecessarily simple. Falling prices in technology are incontrovertible proof of prevailing fair competition, according to proponents of this distinct consumer-price-based approach to antitrust examination. Breaking up tech monopolies will not be easy, but it can be done with a three-pronged approach: preventing anticompetitive mergers and acquisitions, using data as market power to rewrite policy, and raising public awareness about the issue so that citizens can elect antitrust policymakers who are concerned.

Buying off prospective competitors at inflated prices is now part of the corporate playbook in an era of cheap money, with extended periods of very lax monetary policy and massively inflated stock prices. In the internet industry, instances abound, and Facebook’s purchases of Instagram and WhatsApp are unmistakable examples. Excessive regulation does stifle innovation, but free markets rely on it to stay fair and open.

With rare exceptions, current law mandates that any sale worth more than $92 million be disclosed to the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice for scrutiny. Given that one of the stated goals of the Biden order is to improve government examination of mergers and acquisitions, consumers may see greater government legal action to stop agreements that “significantly decrease competition.”

The proposed measure prohibiting certain acquisitions is a welcome indicator that both parties recognize there is misuse, but the bar for offenders remains high, especially since data monopolization isn’t commonly deemed anti-competitive. The FTC and the DOJ will need to use their antitrust enforcement powers against Big Tech, which they will be able to do more effectively under this new legislation.