Climate change can have a significant impact on the health and distribution of forests in the United States. According to some studies, rising temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns can lead to increased stress on trees and greater risk of wildfires, insect infestations, and disease outbreaks. As a result, it is estimated that the total volume of trees in US forests could decline by as much as 21% by the end of the century. This could have far-reaching consequences for the economy, environment, and communities that depend on forests for their livelihoods and well-being.

According to a study led by a North Carolina State University researcher, the inventory of trees used for timber in the continental United States could decline by up to 23% by 2100 under more severe climate warming scenarios. The greatest inventory losses would occur in two of the country’s most important timber regions, both in the South.

According to the researchers, their findings show modest impacts on forest product prices through the end of the century, but larger impacts in terms of carbon storage in US forests. Timberlands account for two-thirds of all forests in the United States.

“We already see some inventory decline at baseline in our analysis, but relative to that, you could lose, additionally, as much as 23% of the U.S. forest inventory,” said the study’s lead author Justin Baker, associate professor of forestry and environmental resources at North Carolina State University. “That’s a pretty dramatic change in standing forests.”

We found pretty high levels of sensitivity to warming and precipitation changes for productive pine species in the South, especially when climate change is combined with high forest product demand growth.

Justin Baker

Researchers used computer modeling to project how 94 individual tree species in the continental United States will grow under six climate warming scenarios through 2100 in the study, which was published in Forest Policy and Economics. They also considered the impact of two different economic scenarios on forestry product demand growth. The researchers compared their results for forest inventory, harvest, prices, and carbon sequestration to no-climate-change scenarios. In comparison to other models, researchers believe their methods could provide a more nuanced picture of the future forest sector under high-impact climate change scenarios.

“Many previous studies paint a fairly optimistic picture for forests under climate change because they see a significant increase in forest growth from additional carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” Baker said. “In some of those models, the effect of carbon dioxide on photosynthesis outweighs the losses caused by precipitation and temperature changes in forest productivity and tree mortality. We have developed a model that is tailored to individual tree species, allowing us to better understand how climate factors influence growth rates and mortality.”

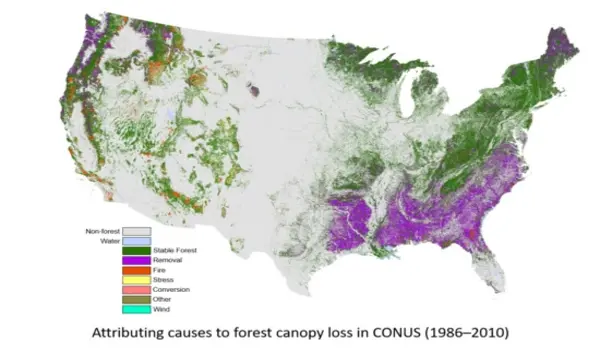

Researchers discovered that in some areas, trees grow more slowly in higher temperatures and die faster. This, combined with rising harvest levels and increased development pressures, resulted in a decrease in total tree inventory. They predicted that the Southeast and South-Central regions, which are two of the three most productive timber supply regions in the United States, would suffer the greatest losses. When compared to one of their baseline scenarios, these regions’ tree inventories could be reduced by up to 40% by 2095. Because of declines in pine products, the researchers predicted that softwood lumber prices could rise by up to 32% by 2050.

“We found pretty high levels of sensitivity to warming and precipitation changes for productive pine species in the South, especially when climate change is combined with high forest product demand growth,” Baker said.

However, the researchers predicted increases in tree supply in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Southwest regions, owing to higher rates of death of certain trees, which resulted in larger harvests at first, followed by the growth of more heat-tolerant species.

“These are regions that are losing a lot of inventory right now as a result of pests and fire disturbance,” Baker explained. “You’re seeing a higher level of replacement with climate-adaptive species like juniper, which are more tolerant of future growing conditions.”

Combining the effects from all the regions, researchers projected total losses of U.S. tree inventory of 3 to 23% compared to baseline. They projected losses in carbon sequestration in most scenarios, and estimated the value of lost carbon stored in U.S. forests up to $5.5 billion per year.

They discovered that the economic impact of climate change on the overall value of the US forest products industry could range from a loss of up to $2.6 billion per year (representing 2.5% of the industry’s value) to a gain of more than $200 million per year.

“We saw that markets could be more resilient than forests,” Baker explained. “Your market effects may appear modest in terms of the impact on consumers and producers, but those impacts are minor in comparison to the carbon sequestration value that forests provide on an annual basis.”