Wetlands are critical ecosystems that play a vital role in maintaining biodiversity, regulating water cycles, and providing numerous ecosystem services. However, wetlands continue to face significant threats, including habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. There is a growing concern that the rate of wetland loss is underestimated, which may hinder conservation efforts.

According to new research, the United States is responsible for more wetland conversion and degradation than any other country. Its findings contribute to a better understanding of the causes and consequences of such losses, as well as to the protection and restoration of wetlands.

The Supreme Court is expected to issue a case ruling this spring or summer that will legally define whether federal protections should be extended to wetlands outside of navigable waters. The justices may want to read a new Stanford-led study that finds that, while wetlands remain threatened in many parts of the world, including the United States, which accounts for more losses than any other country, global wetlands losses have likely been overestimated.

The study’s findings, published in Nature, may help better explain the causes and consequences of wetland loss, allowing for more informed plans to protect or restore ecosystems critical to human health and livelihoods.

“Despite the good news that our findings suggest, it remains critical to halt and reverse the conversion and degradation of wetlands,” said study lead author Etienne Fluet-Chouinard, who was a postdoctoral associate in Stanford’s Department of Earth System Science at the time of the study. “The geographic disparities in losses must be considered because the local benefits lost due to drained wetlands cannot be replaced by wetlands elsewhere.”

These new findings allow us to better quantify changes in wetlands’ carbon sequestration from the atmosphere and methane emissions, another powerful greenhouse gas.

Avni Malhotra

Rethinking wetlands

Wetlands were long thought to be unproductive areas teeming with disease-bearing insects and good only for draining to grow crops or harvesting peat for fuel and fertilizer. Wetlands are now recognized as vital sources of water purification, groundwater recharge, and carbon storage. Wetlands are among the world’s most threatened ecosystems due to unrelenting drainage for conversion to human land uses such as farmland and urban areas, as well as alteration by fires and groundwater extraction.

Understanding the role of wetlands in natural processes and the impact of wetland drainage on the water and carbon cycles requires accurate estimation of the extent, distribution, and timing of wetland loss. A lack of historical data has hindered the effort, forcing scientists to make estimates based on incomplete collections of regional data on wetland loss.

“Wetlands purify our water, prevent flooding, and are biodiversity superheroes,” said study co-author Rob Jackson, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor of Energy and Environment in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “We need the best data possible to save what we have and know what we’ve lost.”

A second chance

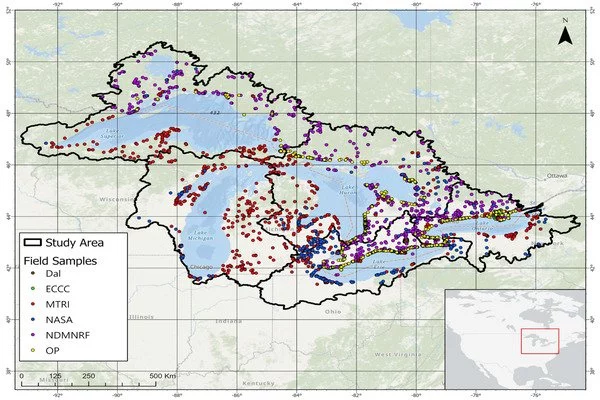

The researchers used a first-of-its-kind historical reconstruction to sift through thousands of records of wetland drainage and land-use changes in 154 countries, mapping the distribution of drained and converted wetlands onto maps of present-day wetlands to get a sense of what the original wetland area might have looked like in 1700.

They discovered that human intervention has reduced the area of wetland ecosystems by 21-35% since 1700. This is significantly less than the 50-87% losses predicted by previous studies. Nonetheless, the authors estimate that at least 1.3 million square miles of wetlands have been lost globally, an area roughly equivalent to Alaska, Texas, California, Montana, New Mexico, and Arizona combined.

“These new findings allow us to better quantify changes in wetlands’ carbon sequestration from the atmosphere and methane emissions, another powerful greenhouse gas,” said study co-author Avni Malhotra, a Stanford postdoctoral researcher at the time of the study.

The low estimate is most likely due to the study’s focus outside of regions with historically high wetland losses, as well as its avoidance of large extrapolations, both of which are characteristics of many previous estimates. The researchers note that their loss estimate is likely conservative because they limited their analysis to available data, which is scarce before 1850.

Despite what appears to be good news, the researchers emphasize that wetland losses have been disproportionately high in some areas, such as the United States, which is estimated to have lost 40% of its wetlands since 1700 and accounts for more than 15% of all global losses during the study’s time period. Although wetland conversion and degradation have slowed globally, it is still occurring in some areas, such as Indonesia, where farmers and corporations continue to clear large swaths of land for oil palm plantations and other agricultural uses.

“Discovering that fewer wetlands have been lost than we previously thought gives us a second chance to take action against further declines,” said study co-author and Cornell University aquatic conservation ecologist Peter McIntyre. “These results provide a guide for prioritizing conservation and restoration.”