A pair of scientists spotted a pinprick of light inching through the constellation Pisces on a Hawaiian mountaintop in the summer of 1992. That unassuming object, located more than a billion kilometers beyond Neptune, would completely rewrite our understanding of the solar system.

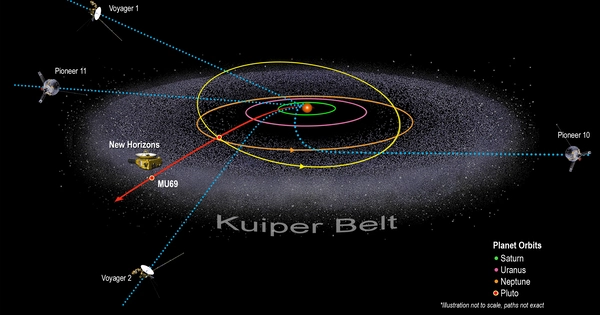

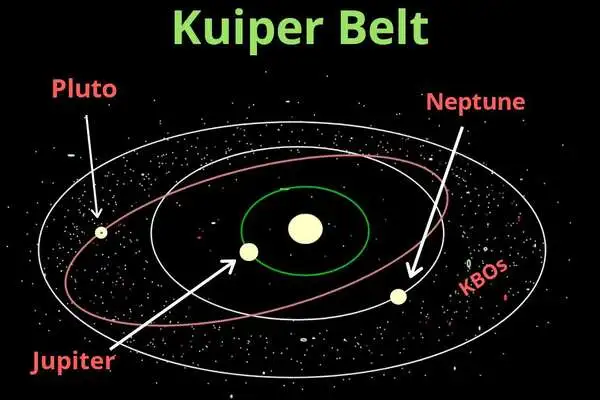

There was something, a vast collection of things, lurking beyond the orbits of the known planets, rather than an expanse of emptiness. The Kuiper Belt, a doughnut-shaped swath of frozen objects left over from the formation of the solar system, had been discovered by the scientists.

The origin and evolution of our solar system are becoming clearer as researchers learn more about the Kuiper Belt. Close-up views of the frozen worlds of the Kuiper Belt have shed light on how planets, including our own, may have formed in the first place. Surveys of this region have revealed thousands of such bodies, known as Kuiper Belt objects, implying that the early solar system was home to pinballing planets.

The humble object that started it all is a 250-kilometer-diameter chunk of ice and rock. This month marks the 30th anniversary of its discovery.

Staring into space

David Jewitt, a planetary scientist, and Jane Luu, an astronomer, were several years into a strange quest in the late 1980s. The pair had been using telescopes in Arizona to photograph patches of the night sky with no specific goal in mind. “We were literally just staring off into space looking for something,” Jewitt, who is now a UCLA student, says.

The researchers were inspired by an apparent mystery: The inner solar system is relatively densely packed with rocky planets, asteroids, and comets, but there didn’t appear to be much beyond the gas giant planets, other than small, icy Pluto. “Perhaps there were things in the outer solar system,” says Luu, who is now affiliated with the Universities of Oslo and Boston.

Poring over glass photographic plates and digital images of the night sky, Jewitt and Luu looked for objects that moved extremely slowly, a telltale sign of their great distance from Earth. But the pair kept coming up empty. “Years went by, and we didn’t see anything,” Luu says. “There was no guarantee this was going to work out.”

The researchers were inspired by an apparent mystery: The inner solar system is relatively densely packed with rocky planets, asteroids, and comets, but there didn’t appear to be much beyond the gas giant planets, other than small, icy Pluto.

Jewitt and Luu

In 1992, the tide shifted. On the night of August 30, Jewitt and Luu were using a University of Hawaii telescope on the Big Island. They were searching for distant objects using their usual method: Take an image of the night sky, wait an hour or so, then take another image of the same patch of sky, and repeat. An object in the outer reaches of the solar system would shift position slightly from one image to the next, owing to the movement of Earth in its orbit. “If it’s a real object, it would move systematically at some predictable rate,” Luu says.

By 9:14 p.m. that evening, Jewitt and Luu had collected two images of the same bit of the constellation Pisces. The researchers displayed the images on the bulbous cathode-ray tube monitor of their computer, one after the other, and looked for anything that had moved. One object immediately stood out: A speck of light had shifted just a touch to the west.

But it was far too early to rejoice. All the time, spurious signals from high-energy particles zipping through space — cosmic rays — appear in images of the night sky. The researchers knew the real test would be whether this speck appeared in more than two images.

Jewitt and Luu waited nervously until 11 p.m. for the telescope’s camera to complete taking a third image. The same object was still there, but it had moved further west. A fourth image, taken shortly after midnight, revealed that the object had moved yet again. Jewitt recalls thinking, “This is something real. We were completely blown away.”

Jewitt and Luu ran some quick calculations based on the object’s brightness and leisurely pace — it would take nearly a month for it to march across the width of the full moon as seen from Earth. This thing, whatever it was, was probably 250 kilometers across. That’s quite large, roughly one-tenth the width of Pluto. It was far beyond Neptune’s orbit. And, more than likely, it wasn’t alone.

Although Jewitt and Luu had been searching the night sky for years, they had only seen a small portion of it. The two concluded that there could be thousands more objects like this one out there just waiting to be discovered.

Just a few months later, Jewitt and Luu spotted a second object also orbiting far beyond Neptune. The floodgates opened soon after. “We found 40 or 50 in the next few years,” Jewitt says. As the digital detectors that astronomers used to capture images grew in size and sensitivity, researchers began uncovering droves of additional objects. “So many interesting worlds with interesting stories,” says Mike Brown, an astronomer at Caltech who studies Kuiper Belt objects.

Finding all of these frozen worlds, some of which orbited even beyond Pluto, made some sense, Jewitt and Luu realized. Pluto has always been an outlier; it’s a cosmic runt (smaller than Earth’s moon) with no resemblance to its gas giant neighbors. Furthermore, its orbit sweeps it far above and below the orbits of the other planets. Jewitt and Luu speculated that Pluto might not belong in the world of the planets, but rather in the realm of whatever lay beyond. “We suddenly realized why Pluto was such a strange planet,” Jewitt says. “It’s just one object, possibly the largest, in a collection of bodies that we just happened upon.”

All eyes on the Kuiper Belt

Astronomers are also surveying the Kuiper Belt with some of the world’s largest telescopes to get a wide-angle view of it. Astronomers recently completed the Outer Solar System Origins Survey at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea, the same mountaintop where Jewitt and Luu discovered 1992 QB1. It discovered over 800 previously unknown Kuiper Belt objects, bringing the total known to around 3,000.

According to MacGregor, the cataloging work is revealing tantalizing patterns in how these bodies move around the sun. Kuiper Belt objects’ orbits tend to be clustered in space rather than being uniformly distributed. That’s a telltale sign that these bodies were pushed by gravity in the past, she says.

The cosmic bullies that did that shoving, most astronomers believe, were none other than the solar system’s gas giants. In the mid-2000s, scientists first proposed that planets like Neptune and Saturn probably pinballed toward and away from the sun early in the solar system’s history. That movement explains the strikingly similar orbits of many Kuiper Belt objects, MacGregor says. “The giant planets stirred up all of the stuff in the outer part of the solar system.”