Discrimination and acculturation are known to have a negative impact on a person’s health. According to a new study from Yale and Columbia University, these painful experiences for pregnant women can also affect the brain circuitry of their children. According to the researchers, these effects are distinct from those caused by general stress and depression.

The findings were reported in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology.

Previous research has shown that high levels of stress and depression are not only harmful to the person experiencing them, but can also have long-term effects on their children if experienced during pregnancy. Discrimination and acculturation, or the changes that occur as a result of migration and the subsequent balancing of multiple, different cultures, have also been shown in recent studies to affect the adult brain. What is less clear is how children’s experiences with discrimination and acculturation may affect them.

Our finding was consistent with what you expect to see in the brain of those affected by early life adversity either pre- or postnatally. We don’t know why this happens. So we need to investigate the biological mechanisms that carry these experiences of adversity from parent to offspring.

Dustin Scheinost

The researchers used established questionnaires to assess the level of discrimination, acculturation, and distress experienced by 165 pregnant women in the new study. The participants were 14 to 19 years old, mostly Hispanic (88%), and lived in or near New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood. After that, the researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess brain connectivity in 38 of the participants’ infants.

The first step, according to the researchers, was to determine whether discrimination and acculturation differed from other types of stress or depression.

“We thought that some of these experiences might go hand-in-hand or overlap, in which case it would be difficult to measure the effects of discrimination or acculturation on their own,” said Dustin Scheinost, associate professor of radiology and biomedical imaging at Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study.

Scheinost and his colleagues from Columbia and Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles used a data analysis program to assess all of their separate questionnaire measures of acculturation, discrimination, stress, depression, childhood trauma, and socioeconomic status and organized them into groups based on how similar the data anlaysis program determined them to be. This, according to the researchers, helped them understand how different measures might be used to evaluate similar experiences.

“That analysis clustered measures of stress and depression and separately pulled out discrimination and acculturation measures as their own distinct variables,” said Scheinost. “That told us that while these experiences of discrimination are related to stress and depression, they are separate enough that we can look at their unique effects.”

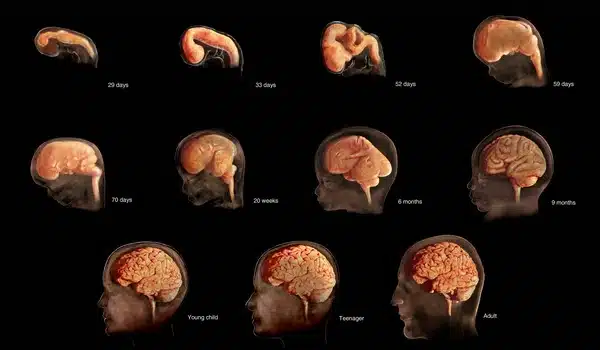

When the research team analyzed the MRI images of the infants’ brains, they found differences in the children whose parents reported experiencing discrimination while pregnant.

According to the researchers, the amygdala is a brain area associated with emotional processing that is extremely vulnerable to prenatal stress. Previous research has shown that early adversity has measurable effects on amygdala connectivity in infants, children, adolescents, and adults. A growing body of evidence also suggests that the amygdala is involved in ethnic and racial processing, such as distinguishing between the faces of people of different races or ethnicities.

When the researchers examined connectivity between the amygdala and another region of the brain known as the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with higher-order functioning, they discovered that children whose mothers experienced more discrimination while pregnant had weaker connectivity between the two brain regions.

“Our finding was consistent with what you expect to see in the brain of those affected by early life adversity either pre- or postnatally,” Scheinost said.

According to Scheinost, the takeaway is that while discrimination and acculturation affect the brain in ways that other types of stress do, there is something special and important about these experiences that should be better understood. Future research, he believes, should focus on whether other populations are similarly affected and what causes the effects.

“We don’t know why this happens,” Scheinost said. “So we need to investigate the biological mechanisms that carry these experiences of adversity from parent to offspring.”