Researchers uncovered previously unknown modifications in a specific type of liver cell, which could pave the way for a novel treatment for liver fibrosis, a potentially fatal condition. There are currently no medications available to treat liver fibrosis.

Hormone therapy is commonly connected with menopause and fertility treatment, but now an SDU-led research team reports that specific intestinal hormones appear to have a favorable influence on the mechanisms that lead to scar tissue formation in the liver (liver fibrosis).

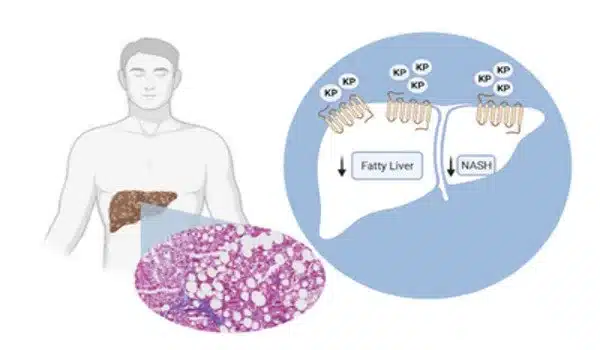

Liver fibrosis can be caused by liver illnesses including metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and there is presently no medical treatment to cure liver fibrosis.

Doctors often try to address the underlying causes of diseases, such as obesity and diabetes, and these treatments may lead to improved liver function over several years but they do not eliminate fibrosis.

When we discovered these cell changes in diseased liver tissue from mice, we went on to look for them in diseased liver tissue from humans. We examined tissue from liver patients from two hospitals in Denmark, and we found the same cell changes in all tissue samples.

Ravnskjaer

Fibrosis is caused by cellular mechanisms that trigger the creation of scar tissue in the liver. A Danish/American research team led by Associate Professor Kim Ravnskjaer from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the ATLAS Center of Excellence reports previously unknown changes in the cell types responsible for fibrosis formation in a new study published in the Journal of Hepatology.

Stellate cells, so named because they resemble stars, are found in the liver. “We’ve discovered a way to deactivate these cells and thus stop the fibrogenic process. This could be a real opportunity to stop the formation of scar tissue,” says Kim Ravnskjaer. The team observed that exposing stellate cells to particular gut hormones can deactivate them.”

“We have focused mainly on the intestinal hormone called vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), which is naturally present in the intestine and neurons, from where it is released when we eat. The liver’s stellate cells, in particular, have a high expression of specific VIP receptors on their surface. VIP stimulates the liver’s blood supply but also appears to keep the stellate cells inactive,” says Kim Ravnskjaer.

The researchers believe that their work could provide the basis for the treatment of liver fibrosis. “This could result in new ways to treat patients. For example, one could develop synthetic hormones designed to target the receptors on specific cells,” Ravnskjaer adds.

Research on liver fibrosis is ongoing worldwide, with many efforts focused on developing effective drugs. Unfortunately, these often come with serious side effects and for this reason, they are not approved.

“If we target these drugs more towards the cell changes we have discovered, we might be able to avoid many of the side effects,” says Kim Ravnskjaer. The results of the research team were initially seen in mice that for a year were fed what the scientist refers to as “a pretty bad western diet”; high in fat and sugar.

“When we discovered these cell changes in diseased liver tissue from mice, we went on to look for them in diseased liver tissue from humans. We examined tissue from liver patients from two hospitals in Denmark, and we found the same cell changes in all tissue samples,” Ravnskjaer says.

The scientists will now look at stellate cells and their surface receptors in patient samples. “The more precisely we can target the right cells, the fewer side effects we will have, and the better for the patient,” says Kim Ravnskjaer, underlining that a new treatment based on these discoveries will be years away.

The Danish National Research Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation-financed Danish Diabetes and Endocrine Academy, and the National Institutes of Health in the United States funded the research.

Concerning liver fibrosis: The production of scar tissue in the liver is referred to as liver fibrosis. It may occur as a result of long-term liver damage and inflammation caused by causes such as alcohol, obesity, diabetes, or viral infection. Fibrosis is the initial stage of cirrhosis, which leads to progressive liver failure, and 80-90 percent of patients with cirrhosis also develop liver cancer.