The gut microbiota has been linked to cancer and has been found to influence anticancer medication efficacy. Resistance to chemo medicines or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is linked to altered gut microbiota, whereas supplementation with specific bacterial species restores responsiveness to anticancer therapies. A growing body of research suggests that altering the gut microbiota can improve the efficacy of anticancer medicines.

A new study summarizes current knowledge about the relationship between the gut microbiota and therapeutic response to immunotherapy, chemotherapy, cancer surgery, and other treatments, pointing to ways the microbiome could be targeted to optimize treatment.

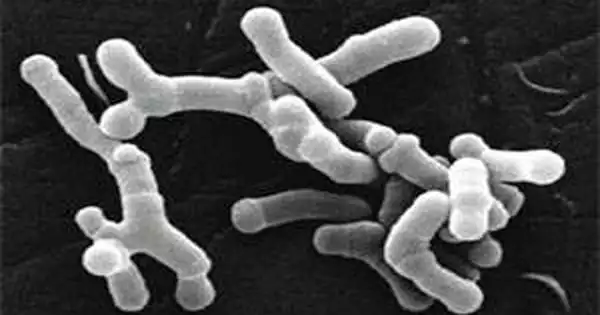

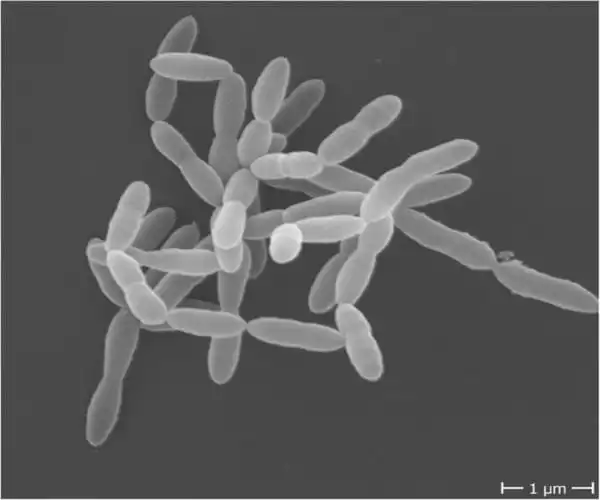

Our gut microbiome, which is home to a diverse range of bacteria, viruses, fungus, and other microbes, has long been assumed to influence many aspects of human health. Recently, sequencing technology has demonstrated that it may also play a role in cancer treatment. A review paper published in JAMA Oncology by Brigham and Women’s Hospital researchers captures the current understanding of the relationship between the gut microbiome and therapeutic response to immunotherapy, chemotherapy, cancer surgery, and other treatments, pointing to ways that the microbiome could be targeted to improve treatment.

We know that a healthy gut is critical to our overall health. Our stomach is so vital that it is frequently referred to as our “second” brain. In recent years, we’ve learned to recognize the gut’s multiple roles, including the gut-brain connection and the gut-immune system relationship.

Khalid Shah

“We know that a healthy gut is critical to our overall health,” said main author Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Stem Cell and Translational Immunotherapy in the Department of Neurosurgery. “Our stomach is so vital that it is frequently referred to as our “second” brain. In recent years, we’ve learned to recognize the gut’s multiple roles, including the gut-brain connection and the gut-immune system relationship. Gut malfunction, or dysbiosis, on the other hand, can be harmful to human health.”

Shah and colleagues describe an increasing role for gut bacteria in immunotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade therapy are innovative cancer treatments, however response varies greatly between individuals and cancer types. Several investigations have shown differences in the species of bacteria detected in fecal samples from responders and non-responders, implying that variable microbiome compositions may influence clinical results. Other research suggests that nutrition and probiotics (living bacterial species that can be consumed), as well as antibiotics and bacteriophages, can impact the composition of the gut microbiome and, as a result, the response to immunotherapy. The authors specifically highlight recent studies on the effects of ketogenic diets for cancer patients.

“Today, discovering medicines that synergize immunotherapies and gut microbiota provides medicine with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to actually influence change in patient care,” Shah added. The authors also discuss how bacteria have been linked to changes in response to chemotherapy and other traditional cancer treatments, as well as how cancer medications can influence the microbiome and create side effects.

“Overall, these findings suggest the possibility of modifying the gut microbiota to reduce the negative effects of traditional cancer treatment,” Shah said.

The authors point out that little is known about what the “ideal” bacteria consortia in the gut look like and how findings from preclinical models may or may not translate into human applications. They emphasize the importance of exercising caution when utilizing probiotics or making dietary adjustments. Many cancer clinical studies are now investigating the role of the microbiome in addressing some of the limitations and gaps in knowledge. Trials of fecal microbial transplantation, nutritional supplements, and new medications that may impact microbiota composition are among them.

“There is compelling evidence that the gut flora can influence cancer therapy,” Shah added. “There are still fascinating options to investigate, such as the impact of a good diet, probiotics, innovative medicines, and more.”

According to current research, the immune system plays a critical role in the etiology of cancer. The immune system can prevent tumor growth by eliminating oncogenic viruses and organisms that cause inflammation. It can also fight cancer development by utilizing tumor immune surveillance, which is focused on identifying precancerous or cancerous cells and destroying them before they cause any harm.

Disclosures: Shah has shares in and serves on the Board of Directors of AMASA Therapeutics, a firm exploring stem cell-based cancer therapeutics; Shah’s interests have been evaluated and are managed in compliance with conflict-of-interest procedures at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare. There were no additional disclosures noted.