For the first time, research led by Associate Professor Duc Dong, Ph.D., demonstrated that the effects of Alagille syndrome, an incurable genetic disorder affecting the liver, could be reversed with a single drug. The study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has the potential to transform treatment for this rare disease and may have implications for more common diseases as well.

“Alagille syndrome is widely considered an incurable disease, but we believe we’re on our way to changing that,” says Dong, who is also the associate dean of admissions for Sanford Burnham Prebys’ graduate school. “We intend to move this drug into clinical trials, and our findings demonstrate its efficacy for the first time.”

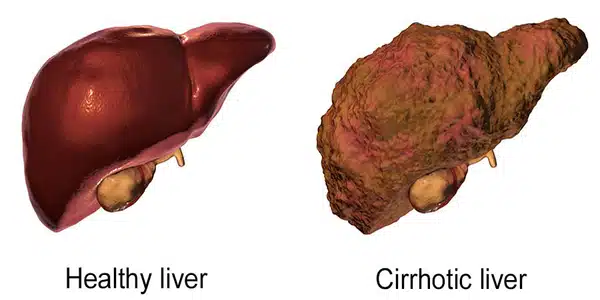

Alagille syndrome, which is caused by a mutation that prevents the formation and regeneration of bile ducts in the liver, affects over 4,000 babies each year. Alagille syndrome children frequently require a liver transplant, but donor livers are limited, and not all Alagille syndrome children qualify. Without a transplant, the disease kills 75% of children by late adolescence.

Our findings suggest that stimulating the Notch pathway with a drug may be sufficient to restore the liver’s normal regenerative potential. The liver is well known for its great capacity to regenerate, but this doesn’t happen in most children with Alagille syndrome because of compromised Notch signaling.

Chengjian Zhao

“Duc and his team continue to do thrilling research on Alagille syndrome, and these breakthroughs certainly offer hope for families living with this very complicated and complex disorder,” says Roberta Smith, CNMT, president of the Alagille Syndrome Alliance. “We have been longtime supporters of Duc’s work and have come to know him as a driven, dedicated scientist who is passionate about moving the needle one step closer toward a cure.”

NoRA1, their new drug, activates the Notch pathway, a cell-to-cell signalling system found in nearly all animals. Notch signalling aids in the orchestration of fundamental biological processes and is implicated in a variety of diseases, including Alagille syndrome. A genetic mutation causes a decrease in Notch signalling in children with Alagille syndrome, resulting in poor liver duct growth and regeneration.

The researchers discovered that in animals with mutations in the same gene that causes Alagille syndrome, NoRA1 increases Notch signalling and causes duct cells in the liver to regenerate and repopulate, reversing liver damage and increasing survival.

Cirrhosis, hepatitis, fatty liver disease, and liver cancer are just a few of the conditions that fall under the category of liver diseases. While some liver diseases can be managed or slowed with medication, lifestyle changes, or surgical interventions, finding a permanent cure for these conditions has proven difficult.

“The liver is well known for its great capacity to regenerate, but this doesn’t happen in most children with Alagille syndrome because of compromised Notch signalling,” says first author Chengjian Zhao, a postdoctoral researcher in Dong’s lab. “Our findings suggest that stimulating the Notch pathway with a drug may be sufficient to restore the liver’s normal regenerative potential.”

The researchers are currently testing the drug on miniature livers cultured in the lab with stem cells derived from the cells of Alagille patients.

“Instead of forcing the cells to do something unusual, we are just encouraging a natural regenerative process to occur, so I’m optimistic that this will be an effective therapeutic for Alagille syndrome,” adds Dong.

Dong is also taking steps to form a start-up company to drive this drug toward clinical trials. The new company will initially focus on Alagille syndrome, but also plans to develop this drug for other, more prevalent diseases, including certain cancers.