According to a new UBC study, unchecked climate change may force some Arctic predators to rely on marine “junk food” to survive. It discovered that changes in the composition and distribution of fish species, as well as the size of fish in Hudson Bay, will begin to accelerate by 2025 and become progressively more extreme unless carbon emissions are reduced.

The researchers used computer models to examine how these changes in prey would affect ringed seals, a common Arctic marine predator. “We discovered that the biomass and distribution of large, fatty Arctic cod may decline dramatically by the end of the century. Smaller fish, such as capelin and sand lance, may become much more common as a result “Katie Florko, a UBC Ph.D. student at the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) and the study’s lead author, agreed. “The number and biomass of fish will increase, as will the diversity of fish, but in smaller packages.”

They estimate that if the atmosphere continues to be impacted by greenhouse gasses, such as carbon dioxide and methane, all varieties of fish in the study will shrink in size.

Climate change will shrink the size of certain fish that seals feed on, forcing them to eat less fulfilling fish. Unchecked climate change may leave some Arctic predators surviving off of marine “junk food,” according to a new UBC study.

This shrinking diet may result in ringed seals—and possibly other Arctic marine predators—gaining less energy during foraging.

“Foraging consumes energy. Is this to say that the seals will have to expend more energy to catch a larger number of these smaller fish for the same amount of energy expended in catching a larger fish?” Florko stated. “It’s similar to how fast food burgers seem to get smaller and smaller every year, and you’re getting less bang for your buck.”

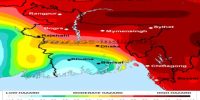

Arctic cod, which live beneath the sea ice, will migrate northwards or become less abundant as the Arctic waters warm. Less heat-sensitive species, such as capelin and sand lance, will become more common in Hudson Bay’s southern region and expand their territory by moving further north. Furthermore, if the atmosphere continues to be polluted with greenhouse gases, all of the fish species studied will shrink in size—roughly 18-35 percent for Arctic cod and 45-82 percent for Pacific sand lance.

According to the model, all fish species shrank in size, but total prey biomass increased by 29%, implying that smaller fish, such as capelin and sand lance, may become more common. ‘It costs energy to forage,’ said UBC student Katie Florko, the study’s lead author.

Florko pointed out that beluga whales could benefit from the predicted changes in the Arctic food web because capelin is a staple of their diet in the summer, but in the fall they rely on Arctic cod to store body fat, so the implications could be complicated.

Because larger fish have more energy reserves to draw on than smaller fish, shrinking in size reduces the distances fish can travel and limits their ability to seek out more suitable environments as the climate changes.

Also, people who eat seals may consume fewer contaminants because the smaller fish predicted to become staples of seal diets are lower down the food web and do not accumulate as many contaminants. Despite these potential benefits, the study’s authors believe that the low-emission scenario is still preferable.

“We’ve never seen such drastic change so quickly,” said Travis Tai, a Ph.D. graduate of the IOF and study co-author. “We’re gambling, and we don’t know what will happen. When there are dramatic shifts in food web structures, we can expect large changes not only in how species like ringed seals use the oceans but also in how people use the oceans.”

The study, titled “Predicting how climate change threatens Arctic marine predators’ prey base,” was published in the journal Ecology Letters.