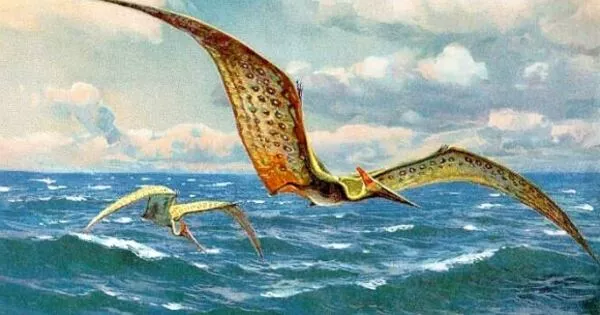

A new species of pterosaur from Angola’s Atlantic coast has been identified, with wings that span nearly 16 feet. Epapatelo otyikokolo was named by an international team that included two vertebrate paleontologists from SMU. This dinosaur-era flying reptile was discovered in the same region of Angola where large marine animal fossils are currently on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

According to team member Michael J. Polcyn, research associate in the Huffington Department of Earth Sciences and senior research fellow, ISEM at SMU, pterosaur fossils dating back to the Late Cretaceous are extremely rare in Sub-Saharan Africa (Southern Methodist University).

“This new discovery provides us with a much better understanding of the ecological role of the creatures that flew above the waves of Bentiaba, on Africa’s west coast, approximately 71.5 million years ago,” Polcyn said.

This new discovery provides us with a much better understanding of the ecological role of the creatures that flew above the waves of Bentiaba, on Africa’s west coast, approximately 71.5 million years ago.

Michael J. Polcyn

The research also included collaboration from renowned paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs, SMU professor emeritus of earth sciences and president of ISEM, the university’s interdisciplinary institute. The findings of the team were published in the journal Diversity.

Epapatelo otyikokolo is thought to be a fish-eating pterosaur that acted like large modern-day seabirds.

“They probably spent time flying above open-water environments and diving to feed, similar to how gannets and brown pelicans do today,” Jacobs said. “Epapatelo otyikokolo was a large animal with a wingspan of about 4.8 m, or nearly 16 feet.”

But fossils discovered since the study suggest that some of the newly identified pterosaur species could have been even larger creatures, Polcyn said. Pterosaurs were impressive creatures, with some of the largest species having wingspans of nearly 35 feet.

The genus name ‘Epapatelo’ is the translation of the word from the Angolan Nhaneca dialect meaning “wing,” and the species name “otyikokolo” is the translation of ‘lizard.’ The Nhaneca or Nyaneka people are an Indigenous group from Angola’s Namibe Province, the region where the fossils were found.

The lead author of the study was Alexandra E. Fernandes, of Museu da Lourinhã, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa and The Bavarian State Collection for Paleontology and Geology. Other co-authors include Octávio Mateus of Universidade NOVA de Lisboa and Museu da Lourinhã; Brian Andres of the University of Sheffield; Anne S. Schulp of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and Utrecht University in the Netherlands; and Antonio Olímpio Gonçalves of the Universidade Agostinho Neto in Angola.

Jacobs and Polcyn formed the Projecto PaleoAngola collaboration with collaborators in Angola, Portugal, and the Netherlands to explore and excavate Angola’s rich fossil history, laying the groundwork for the fossils to be returned to the West African nation. Back in Dallas, Jacobs, Polcyn, and research associate Diana Vineyard worked with a small army of SMU students for 13 years to prepare the fossils excavated by Projecto PaleoAngola.

Beginning in 2005, this international team discovered and collected the fourteen Epapatelo otyikokolo bones in Bentiaba, Angola. Bentiaba is situated on a stretch of Angolan coastline that Jacobs refers to as a “museum in the ground” due to the abundance of fossils discovered in the rocks there.

Many of those fossils are currently on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History as part of the “Sea Monsters Unearthed” exhibit, which was co-produced with SMU. It depicts Cretaceous-era large marine reptiles such as mosasaurs, turtles, and plesiosaurs.