The discovery provides a new causal explanation for the condition that affects 1-2 percent of adults. The discovery, which was published in the European Heart Journal, provides a new causal explanation for the condition that affects 1-2 percent of adults. (In the United Kingdom, this equates to approximately 1,250-2,500 people.)

As a result of the research, the new causal variants, known as truncating ALPK3 (alpha-protein kinase) variants, should be included in genetic testing/screening, allowing doctors to identify a larger number of people who are at risk of developing the condition and would benefit from regular monitoring.

Heart muscles thicken in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, making it more difficult for the heart to receive and pump blood. While the condition does not usually interfere with daily life, it can cause heart failure and is frequently cited as the leading cause of sudden unexpected death in young people. Approximately half of the cases already have known genetic causes, which have been linked to eight to ten specific genes (only two of these single genes were found in the last decade).

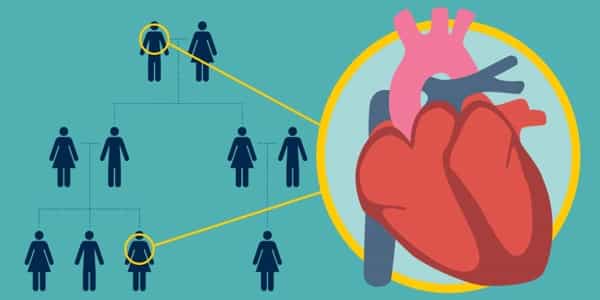

A UCL-led research team has identified a new gene as a cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, an inherited heart condition affecting one in 500 people.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an extremely common genetic condition,” said lead author Dr. Luis Lopes (UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Science) and Consultant Cardiologist at Barts Health NHS Trust. Previously, small-scale studies suggested that ALPK3 gene variants could be the cause of a rare pediatric form of cardiomyopathy, but only if two abnormal copies were inherited. Using a large number of patients and families, we have now demonstrated that just one abnormal copy is enough to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in adults. Because inheriting just one abnormal copy of a gene is more likely than inheriting two, this type of inheritance (autosomal dominant) is much more common.

“Identifying a new genetic cause is critical because it opens up new avenues for potential treatment. It also allows families who have been affected by the condition but did not know why to know that a cause for their specific cause has been discovered.”

An international team of researchers examined the genomes of 2,817 people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred from centers in Spain, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Russia, Latvia, Brazil, and Argentina for the new study. They compared the prevalence of ALPK3 variants to that of the general population and discovered that it was 16 times higher.

Researchers also looked at the presence of the variant within families to see if it was causal by seeing if the variant tracked with the disease – that is, whether family members who had the variant also had the disease.

The researchers compared the disease’s distinct nature to when it was caused by flaws in the sarcomere genes – the primary way the disease is inherited. (They are called sarcomere genes because their function is related to sarcomeres, which are the basic contractile unit, or primary building block, of muscle fiber.)

They discovered that in cases where the new gene was implicated, the disease was diagnosed later (at an average age of 56), but had the same rates of heart failure and heart transplantation as cases linked to sarcomere genes. While little is known about the functional consequences of ALPK3 variants, they are thought to play a role in protein function regulation via phosphorylation. Proteins play an important role in the contraction and relaxation of heart muscle cells.

Dr. Lopes stated: “ALPK3 variants contribute to the disease in a different way than the other main sarcomere gene causes. This discovery is exciting because it will lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets. We must now investigate the mechanisms by which the ALPK3 variants are linked to the condition.”

In the United Kingdom, genetic testing is available to all patients diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy at referral centers such as Barts Heart Centre, as well as family members if a genetic cause is known. While there is no cure at the moment, people with the condition are regularly monitored, medicated, and one important intervention is the placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), a device similar to a pacemaker that can deliver a powerful electric shock to the heart if it detects a dangerously abnormal heartbeat. The study was supported by the Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation.