Looking at people’s ability to sound out words after a stroke, researchers discovered that knowing which region of the brain was affected by the stroke could have significant implications for helping to target rehabilitation efforts.

Many different types of dyslexia are caused by stroke. This variation reflects two factors: 1) the organization of normal reading ability in the brain, and 2) the size and location of an individual stroke. The left hemisphere of the brain is responsible for most language functions, including reading, but the right hemisphere has some normal reading ability. As a result, a person suffering from a left hemisphere stroke can regain some reading ability through both the injured left hemisphere and the right hemisphere.

When Georgetown University researchers studied people’s ability to sound out words after a stroke, they discovered that knowing which region of the brain was affected by the stroke could have significant implications for helping to target rehabilitation efforts. The discovery was published in the journal Brain Communications.

The goal of this study was to understand how post-stroke difficulties with three different aspects of phonology relate to reading difficulties. People read words in two ways: one involves sounding out words, which is especially important when learning new words, and the other involves whole-word recognition. People with post-stroke language impairment frequently struggle to sound out words.

J. Vivian Dickens

“In the United States, one in every five stroke survivors has persistent language impairment. The majority of these people also have difficulty reading “J. Vivian Dickens, Ph.D., a Georgetown University MD/Ph.D. student conducting research in the university’s Cognitive Recovery Lab and Center for Aphasia Research and Rehabilitation at Georgetown’s Medical Center is the study’s first author. “Our findings shed light on the neuroanatomical and cognitive bases of post-stroke reading and language deficits, which may aid in the prediction of deficits in stroke survivors and the development of targeted treatments.”

The study focused on phonological processing, which is the understanding and use of the sounds that comprise language. This processing has three major components: auditory, or the ability to recognize the sounds of words, such as determining whether words rhyme; motor, or the ability to produce accurate and clear speech; and auditory-motor translation, or the translation of sounds heard into speech.

“The goal of this study was to understand how post-stroke difficulties with three different aspects of phonology relate to reading difficulties,” Dickens explains. “People read words in two ways: one involves sounding out words, which is especially important when learning new words, and the other involves whole-word recognition. People with post-stroke language impairment frequently struggle to sound out words.”

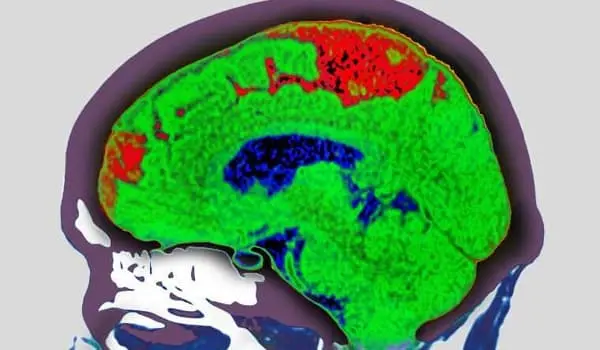

The researchers assessed 67 people’s reading and phonological abilities, 30 of whom had had a stroke and 37 who had not. The researchers were able to trace out white matter connections, which are similar to wiring diagrams for the brain, as well as map out stroke locations in the brains of affected study participants using advanced MRI techniques.

“We discovered two distinct patterns of reading difficulties. Strokes to the left frontal lobe disrupted motor phonology and one of the two reading methods, specifically sounding out words. Strokes to the left temporal and parietal lobes, on the other hand, caused problems with auditory-motor translation and both ways of reading “Dickens says “These findings may aid clinicians in developing therapies aimed at specific reading problems that individual stroke survivors frequently face.”

“This study focused on reading single words aloud, a classic measure of reading ability,” says Peter E. Turkeltaub, MD, Ph.D., director of the Cognitive Recovery Lab in the Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery, medical director in the Center for Aphasia Research and Rehabilitation, and senior author of the study. “Our findings represent an important step forward in elucidating the mechanisms of translating print to sound, which is critical for developing rehabilitative therapies for stroke patients.”

The researchers are planning studies to help confirm how far these findings can be generalized to silent reading, which relies on the same core psychological processes as oral reading and is more important for everyday reading. The researchers are also hoping to turn their research tasks into useful clinical tests to diagnose phonological processing.

Some people with acquired dyslexia struggle to read sentences or paragraphs because they can’t focus their visual attention on a single word at a time. Visual distraction can be reduced by cutting a “window” in a piece of paper and then moving the window along a line of text so that one word at a time can be read.

Everyone’s recovery time after a stroke is different—it can take weeks, months, or even years. Some people recover completely, while others have long-term or permanent disabilities. Following a stroke, therapy and medication may help with depression or other mental health conditions. Participating in a patient support group may assist you in adjusting to life after a stroke. Talk with your health care team about local support groups, or check with an area medical center.