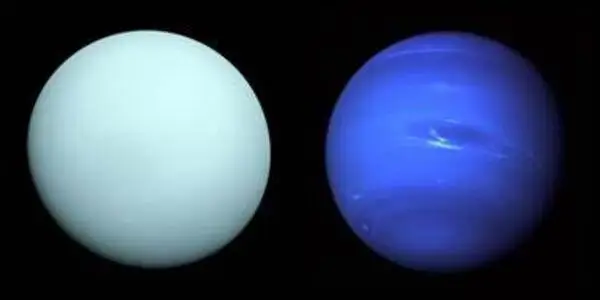

Neptune is well-known for its beautiful blue color and Uranus for its green color, but a new study has discovered that the two ice giants are far closer in color than previously believed. The right planet hues have been confirmed thanks to research led by Professor Patrick Irwin of the University of Oxford, which was published today in the Royal Astronomical Society’s Monthly Notices.

He and his team discovered that both worlds are a similar shade of greenish blue, contrary to popular opinion that Neptune is a deep azure while Uranus is pale cyan. Astronomers have long recognized that most current photographs of the two planets do not adequately represent their real colors.

The misunderstanding developed because photographs of both planets collected throughout the twentieth century, including those taken by NASA’s Voyager 2 mission, the sole spacecraft to sail past these worlds, were recorded in different hues.

The single-color photos were eventually recombined to make composite color images, which were not always correctly balanced to achieve a “true” color image and, in the case of Neptune, were frequently made “too blue.”

Furthermore, the early Neptune photographs from Voyager 2 were heavily contrast boosted to better depict the clouds, bands, and winds that define our present view of Neptune.

This is the first study to match a quantitative model to imaging data to explain why the colour of Uranus changes during its orbit. In this way, we have demonstrated that Uranus is greener at the solstice due to the polar regions having reduced methane abundance but also an increased thickness of brightly scattering methane ice particles.

Professor Irwin

Professor Irwin said: “Although the familiar Voyager 2 images of Uranus were published in a form closer to ‘true’ colour, those of Neptune were, in fact, stretched and enhanced, and therefore made artificially too blue. Even though the artificially-saturated colour was known at the time amongst planetary scientists — and the images were released with captions explaining it — that distinction had become lost over time. Applying our model to the original data, we have been able to reconstitute the most accurate representation yet of the colour of both Neptune and Uranus.”

In the new study, the researchers used data from Hubble Space Telescope’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. In both instruments, each pixel is a continuous spectrum of colours. This means that STIS and MUSE observations can be unambiguously processed to determine the true apparent colour of Uranus and Neptune.

The researchers used these data to re-balance the composite colour images recorded by the Voyager 2 camera, and also by the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). This revealed that Uranus and Neptune are actually a rather similar shade of greenish blue. The main difference is that Neptune has a slight hint of additional blue, which the model reveals to be due to a thinner haze layer on that planet.

The study also provides an answer to the long-standing mystery of why Uranus’s colour changes slightly during its 84-year orbit of the Sun. The authors came to their conclusion after first comparing images of the ice giant to measurements of its brightness, which were recorded by the Lowell Observatory in Arizona from 1950 — 2016 at blue and green wavelengths.

These measurements showed that Uranus appears a little greener at its solstices (i.e. summer and winter), when one of the planet’s poles is pointed towards our star. But during its equinoxes — when the Sun is over the equator — it has a somewhat bluer tinge.

Part of the reason for this was known to be because Uranus has a highly unusual spin. It effectively spins almost on its side during its orbit, meaning that during the planet’s solstices either its north or south pole points almost directly towards the Sun and Earth. This is important, the authors said, because any changes to the reflectivity of the polar regions would therefore have a big impact on Uranus’s overall brightness when viewed from our planet.

What astronomers were less clear about is how or why this reflectivity differs. This led the researchers to develop a model which compared the spectra of Uranus’s polar regions to its equatorial regions. It found that the polar regions are more reflective at green and red wavelengths than at blue wavelengths, partly because methane, which is red absorbing, is about half as abundant near the poles than the equator.

However, this wasn’t enough to fully explain the colour change so the researchers added a new variable to the model in the form of a ‘hood’ of gradually thickening icy haze which has previously been observed over the summer, sunlit pole as the planet moves from equinox to solstice.

Astronomers think this is likely to be made up of methane ice particles. When simulated in the model, the ice particles further increased the reflection at green and red wavelengths at the poles, offering an explanation as to why Uranus is greener at the solstice.

Professor Irwin said: “This is the first study to match a quantitative model to imaging data to explain why the colour of Uranus changes during its orbit. In this way, we have demonstrated that Uranus is greener at the solstice due to the polar regions having reduced methane abundance but also an increased thickness of brightly scattering methane ice particles.”

Dr Heidi Hammel, of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), who has spent decades studying Neptune and Uranus but was not involved in the study, said: “The misperception of Neptune’s colour, as well as the unusual colour changes of Uranus, have bedevilled us for decades. This comprehensive study should finally put both issues to rest.”

The ice giants Uranus and Neptune remain a tantalising destination for future robotic explorers, building on the legacy of Voyager in the 1980s.

Professor Leigh Fletcher, a planetary scientist at the University of Leicester and co-author of the new study, stated, “A mission to explore the Uranian system — from its bizarre seasonal atmosphere to its diverse collection of rings and moons — is a high priority for space agencies in the coming decades.”

Even a long-lived planetary explorer in orbit around Uranus would only acquire a brief glimpse of a Uranian year.

“Earth-based studies like this, showing how Uranus’ appearance and colour has changed over the decades in response to the weirdest seasons in the Solar System, will be vital in placing the discoveries of this future mission into their broader context,” he said.