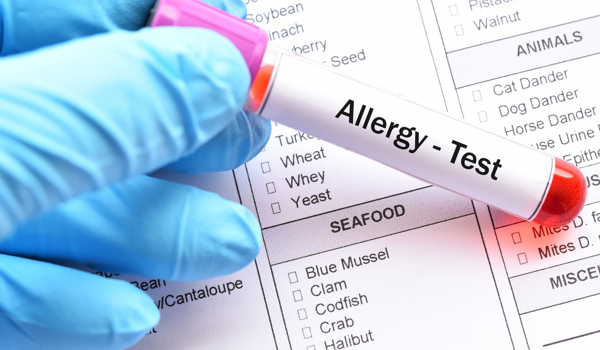

Allergies are common, but their identification is difficult, and the chances of success with medication vary based on the type of allergy. So far, skin tests have been unappealing, time-consuming, and risky in terms of eliciting an adverse reaction. Researchers at the University of Bern and Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, have now devised a revolutionary test that greatly simplifies allergy diagnosis and predicts therapy success with high accuracy.

One-third of the world’s population suffers from one or more allergies, and the number is growing every year. Type I allergy, often known as immediate-type allergy, is by far the most common type of allergy. This includes allergic rhinitis (hay fever), allergic asthma, food allergies, and allergies to insect venoms, pollen, grasses, or home dust mites, among other things. It is an immune system overreaction to genuinely harmless foreign components (allergens), which often develops within seconds or minutes of interaction with the allergen. Allergic symptoms can range from skin redness and swelling to itching and shortness of breath, as well as anaphylactic shock and death.

The process of determining an allergy is complicated: In addition to the medical history (anamnesis), test parameters with often ambiguous diagnostic values are considered, and patients are subjected to skin testing. Such skin tests are uncomfortable, at times painful, time-consuming, and carry the danger of inducing an allergic reaction. Allergies are treated by symptom management and, in severe situations, immunotherapy. This includes injecting increasing concentrations of an allergen under the patient’s skin over a five-year period in order to desensitize the patient to the allergen. Immunotherapy is not always effective: There is currently no credible mechanism for estimating the likelihood of success prior to beginning such therapy.

We are convinced that with this test, we will be able to determine whether and to what extent an immunotherapy is beneficial within a few months after starting it. This would be a valuable tool for the allergologist treating the patient in determining whether it makes sense to continue the therapy or not.

Thomas Kaufmann

A research group led by Alexander Eggel from the Department for BioMedical Research (DBMR) at the University of Bern and the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, together with Thomas Kaufmann from the Institute of Pharmacology at the University of Bern, has now developed an allergy test that, on the one hand, greatly simplifies diagnosis and, on the other hand, can reliably predict the success of immunotherapy. The test was recently presented in a publication of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

In vitro mast, cells provide unprecedented reliability

Type I allergy develops when the body generates antibodies of the immunoglobulin E (IgE) class in reaction to allergens. IgE antibodies bind to IgE receptors on the surface of specialized immune cells called mast cells in the body. Subsequent interaction with the same allergens activates the mast cells, resulting in the production of inflammatory mediators such as histamine or leukotrienes, which cause allergic symptoms.

For their unique allergy test, the researchers lead by Alexander Eggel and Thomas Kaufmann created a new in vitro cell culture that, with the help of a few molecular biology procedures, can manufacture practically any desired number of mature mast cells in a matter of days. These mast cells have IgE receptors on their surface and respond remarkably similarly to mast cells in the human body when exposed to IgE and allergens. In the test, these mast cells are exposed to blood serum from allergic persons, which bind the IgE antibodies in the serum to the cells, and then activated with the allergens to be examined. At this point, the activation of the cells can be quantified very easily and quickly using so-called flow cytometry.

“We were both shocked and happy to discover that our mast cells could be triggered virtually completely. There are no comparable cell lines that can be triggered as well as these, as far as we know “Alexander Eggel reveals. He continues: “Another significant benefit is that the test uses blood, which is quite stable and can be held frozen for a long period, allowing for retrospective tests and studies. Other equivalent tests, on the other hand, use entire blood, which cannot be kept and must be processed within hours.”

The high-throughput approach enables application on a larger scale

To run a large number of experiments, the researchers devised a high-throughput technique in which up to 36 conditions can be assessed in a single test tube. This enables the testing of several allergens with a single blood serum or multiple sera for the same allergy. “A trained person can already execute roughly 200 tests per day using this approach, and the process will be further streamlined,” says Noemi Zbären, the main author of the study at DBMR.

Great potential for various applications

The researchers believe that, in addition to the initial identification of allergies, the test will have other significant applications. “We are convinced that with this test, we will be able to determine whether and to what extent an immunotherapy is beneficial within a few months after starting it,” says Thomas Kaufmann. “This would be a valuable tool for the allergologist treating the patient in determining whether it makes sense to continue the therapy or not.” According to the researchers, the test offers significant promise for monitoring therapeutic efficacy and duration of action for new allergy drugs in clinical trials, as well as determining potential allergic reactions and quality control of food products.

And academic research should not be neglected either. “The new cell line — and already planned modifications to the same — will enable us to address many of the still unanswered questions in allergy research,” explains Alexander Eggel.