The African continent is slowly separating into several large and small tectonic blocks

The African continent is slowly separating into a number of large and small tectonic blocks along with the diverging East African Rift System, continuing to Madagascar – the long island just off the coast of Southeast Africa – that itself will likewise disintegrate into smaller sized islands. The finding comes in a new research study by D. Sarah Stamps of the Department of Geosciences for the journal Geology.

The African continent is slowly separating into several large and small tectonic blocks along with the diverging East African Rift System, continuing to Madagascar – the long island just off the coast of Southeast Africa — that itself will also break apart into smaller islands.

In prehistoric times around 88 million years ago, Madagascar, the island country in the Indian Ocean off the east coast of Africa, split off from the Indian subcontinent. Now, a new study shows the island is breaking up again, this time into smaller islands. These developments will redefine Africa and the Indian Ocean. The breakup is a continuation of the shattering of the supercontinent Pangea some 200 million years ago. Rest assured, though, this isn’t happening anytime soon.

“The rate of present-day separation is millimeters annually, so it will be millions of years prior to new oceans begin to form,” stated Stamps, an assistant teacher in the Virginia Tech College of Science. “The rate of extension is fastest in the north, so we’ll see brand-new oceans forming there first.”

The new GPS dataset of very precise surface motions in Eastern Africa, Madagascar, and several islands in the Indian Ocean reveals that the break-up process is more complex and more distributed than previously thought, according to the study, completed by Stamps with researchers from the University of Nevada-Reno, the University of Beira Interior in Portugal, and the Institute and Observatory of Geophysics of Antananarivo at the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar itself.

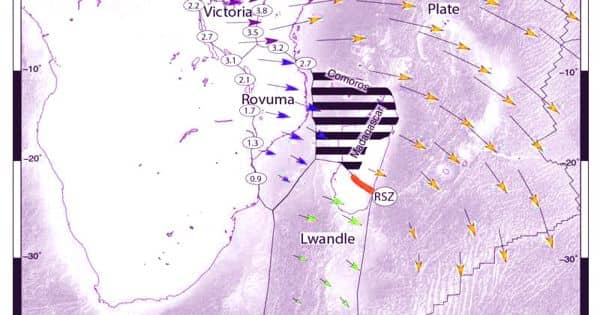

In one area, the scientists found that extension is dispersed throughout a broad location. The area of the distributed extension is about 600 kilometers (372 miles) large, spanning from Eastern Africa to entire parts of Madagascar. More specifically, Madagascar is actively breaking up with southern Madagascar moving with the Lwandle microplate– a small tectonic block– and a piece of main Madagascar is moving with the Somalian plate. The rest of the island is found to be warping nonrigidly, Stamps added.

While studies have shown the African continent and now the Madagascar island is actively splitting or breaking apart to form a new continent, ocean, or island, this is not happening anytime soon. Also working on the paper was geosciences Ph.D. student Tahiry Rajaonarison, who previously was a master’s student at the Madagascar’s University of Antananarivo. He assisted Stamps in 2012 in collecting GPS data that was used in this study.

The group used new surface movement information and additional geologic information to test various configurations of tectonic blocks in the area utilizing computer system models. Through an extensive suite of statistical tests, the scientists defined new limits for the Lwandle microplate and Somalian plate. This approach permitted screening if surface movement information is consistent with rigid plate movement.

The final model for the East African Rift System.

The discovery of the broad deforming zone helps geoscientists comprehend recent and ongoing seismic and volcanic activity happening in the Comoros Islands, found in the Indian Ocean in between East Africa and Madagascar. The research study likewise provides a framework for future studies of international plate movements and investigations of the forces driving plate tectonics for Stamps and her group.