Water was once present in a region of Mars known as Arabia Terra, according to scientists. Ari Koeppel, a Ph.D. candidate at Northern Arizona University, recently discovered that water was once present in the Arabia Terra region of Mars as part of a team of collaborators from Northern Arizona University and Johns Hopkins University.

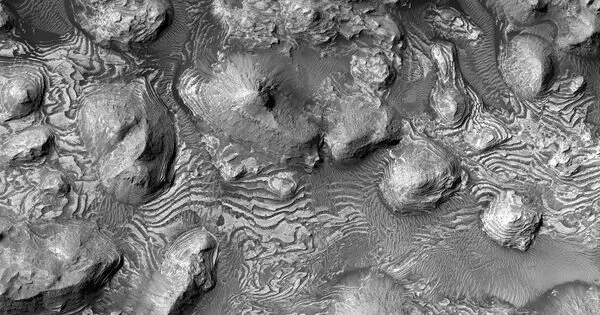

Arabia Terra is located in Mars’ northern latitudes. This ancient land, named in 1879 by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, covers an area slightly larger than the European continent. Arabia Terra is home to craters, volcanic calderas, canyons, and beautiful bands of rock resembling the Painted Desert or the Badlands.

The research focus for Koeppel and his advisor, associate professor Christopher Edwards of NAU’s Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science, as well as Andrew Annex, Kevin Lewis, and undergraduate student Gabriel Carrillo of Johns Hopkins University, was on these rock layers and how they formed. Their research, titled “A fragile record of fleeting water on Mars,” was funded by NASA’s Mars Data Analysis Program and was published in the journal Geology recently.

“We were specifically interested in using rocks on the surface of Mars to get a better understanding of past environments three to four billion years ago and whether there could have been climatic conditions that were suitable for life on the surface,” Koeppel said. “We were interested in whether there was stable water, how long there could have been stable water, what the atmosphere might have been like and what the temperature on the surface might have been like.”

We were specifically interested in using rocks on the surface of Mars to get a better understanding of past environments three to four billion years ago and whether there could have been climatic conditions that were suitable for life on the surface.

Ari Koeppel

To gain a better understanding of what happened to create the rock layers, the scientists focused on thermal inertia, which defines a material’s ability to change temperature. Sand, with its small and loose particles, quickly gains and loses heat, whereas a solid boulder will remain warm long after dark. They were able to determine the physical properties of rocks in their study area by observing surface temperatures. They could tell if a material was loose and eroding away even if it appeared to be solid.

“No one had done an in-depth thermal inertia investigation of these really interesting deposits that cover a large portion of the surface of Mars,” Edwards said.

Koeppel used remote sensing instruments on orbiting satellites to complete the research. “Like geologists on Earth, we look at rocks to try to tell stories about past environments,” Koeppel explained. “We have fewer options on Mars. We can’t just go to a rock outcrop and collect samples; we rely heavily on satellite data. So there are a few satellites orbiting Mars, and each satellite houses a collection of instruments. Each instrument plays a unique role in assisting us in describing the rocks on the surface.”

They looked at thermal inertia as well as evidence of erosion, the condition of the craters, and what minerals were present in a series of investigations using this remotely gathered data.

“We figured out these deposits are much less cohesive than everyone previously thought they were, indicating that this setting could only have had water for only a brief period of time,” said Koeppel. “For some people, that kind of sucks the air out of the story because we often think that having more water for more time means there’s a greater chance of life having been there at one point. But for us, it’s actually really interesting because it brings up a whole set of new questions.

What are the conditions that could have allowed water to exist for such a short period of time? Could there have been glaciers that melted quickly, causing massive floods to erupt? Could there have been a groundwater system that percolated up from the ground for a brief period of time before sinking back down?”

Koeppel began his college career in engineering and physics but switched to geological sciences while earning his master’s degree at The City College of New York. He came to NAU to work with Edwards and to immerse himself in Flagstaff’s thriving planetary science community.

“I became interested in planetary science because of my curiosity about worlds other than Earth. Even Mars is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the size of the universe “said Koeppel. “But we’ve been studying Mars for a few decades now, and we’ve accumulated a massive amount of data. We’re starting to study it at levels comparable to how we studied Earth, and it’s an exciting time for Mars science.”