Healthy immune cells are still forming 18 years after blood stem cell transplantation in patients with faulty immune systems, according to new research. An international collaboration between Great Ormond Street Hospital, the UCL GOS Institute for Child Health, and Harvard Medical School has shown that the beneficial effects of gene therapy can be seen decades after the transplanted blood stem cells have been cleared by the body.

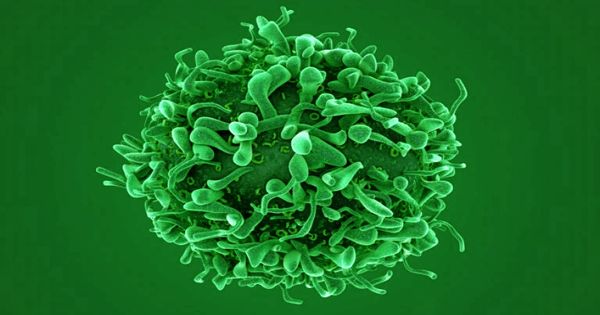

Gene therapy is a type of treatment that is used to treat diseases by modifying the expression of an individual’s genes or correcting abnormal genes. The research team followed five patients who were successfully cured of SCID-X1 at GOSH using gene therapy. For three to eighteen years, patients’ blood was routinely tested to determine which cell types and biomarker chemicals were present. The findings revealed that, even though the stem cells used in gene therapy had been cleared by the patients, the critically corrected immune cells, known as T-cells, were still forming.

Researchers have shown that the beneficial effects of gene therapy can be seen decades after the transplanted blood stem cells have been cleared by the body.

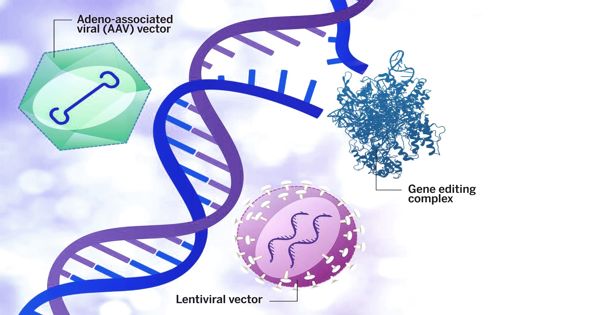

Gene therapy works by first removing some of the patients’ blood-forming stem cells, which are responsible for the formation of all types of blood and immune cells. In a laboratory, a viral vector is then used to deliver a new copy of the faulty gene into the DNA of the patients’ cells. These corrected stem cells are then returned to patients in a procedure known as a “autologous transplant,” where they continue to produce a steady supply of healthy immune cells capable of fighting infection.

The corrected stem cells in the SCID-X1 gene therapy were eventually cleared by the body, but the patients remained cured of their condition. The ‘cure,’ according to this group of researchers, was due to the body’s ability to continually produce newly-engineered T cells, which are an important part of the body’s immune system.

Gene therapy is an experimental technique designed to introduce genetic material into cells to compensate for defective genes. It works by first collecting some of the patients’ blood-forming stem cells, which generate all types of blood and immune cells. The genetically-engineered correct gene is then inserted into the DNA of the faulty cells in the laboratory using a carrier called a vector. Finally, the corrected stem cells are reintroduced into the patient, where they begin to produce a steady supply of healthy immune cells capable of fighting infections.

They used cutting-edge gene tracking technology and a battery of tests to provide unprecedented information about T cells in SCID-X1 patients decades after gene therapy. The researchers believe that this gene therapy has created the ideal conditions for the human thymus (the part of the body where T cells develop) to maintain a long-term supply of the right type of progenitor cells that can form new T cells. Further research into how this occurs and how it can be used could be critical for the development of next-generation gene therapy and cancer immunotherapy approaches.

While the corrected stem cells were cleared by the body, the five SCID-X1 patients remained healthy and continued to produce T-cells for decades after the gene therapy treatment. The British-American team hypothesized that the human thymus – the organ that produces all blood and immune cells – could serve as a long-term repository of specialized stem cells, also known as ‘progenitor cells,’ capable of generating new T-cells.

‘We were very excited when we discovered that newly-engineered T-cells were being actively produced in patients many years after receiving engineered stem cells. We had predicted the existence of a long-term store of cells in the thymus capable of transforming into T-cells, but now we had proof.’ said Dr Biasco.