Impact of Recreational Activity on Wildlife Habitats

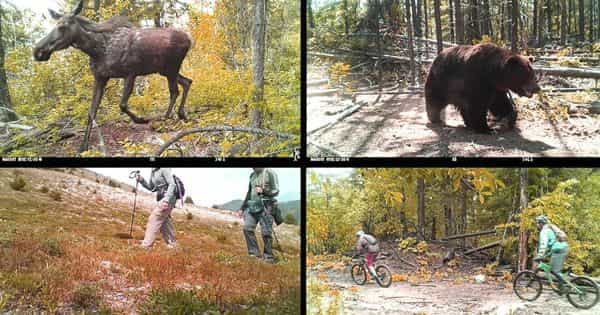

This complex web of life provides the natural systems we depend on – giving us essentials like water, clean air, fertile soils, and a stable climate. Our planet’s wildlife is in crisis – numbers have fallen by more than half since 1970, and species are going extinct at an alarming rate. Recreation activities relating to water and wildlife, such as fishing, hunting, wildlife viewing, canoeing, and boating, are popular in both Forests. NSRC researchers established a baseline understanding of human recreation impacts on wildlife communities in the Adirondack Park of New York. Researchers placed motion-activated cameras on the trails in and around the South Chilcotin Mountains Provincial Park in southwestern B.C., a region popular for its wildlife and recreational activities such as hiking, horseback riding, ATV riding, and mountain biking. Researchers developed a spatial model of estimated recreation visitation and summarized measures of recreational use from two sources of observations. If recreation affects the density or distribution of species that functionally dominate a community or ecosystem, resulting impacts will be especially severe. Habitat changes that alter the type, distribution, and food amount available will impact animals, whether in water or on land

They applied these models in combination with large-scale and long-term data to examine potential impacts of recreation on bird and mammal communities. Overall, they found that environmental factors — like the elevation or the condition of the forest around a camera location — were generally more important than human activity in determining how often wildlife used the trails. They also implemented a pilot field study to test methods for monitoring exposure of shoreline and upland habitats to water-based and shoreline recreation activities. We need to reverse this loss of nature and create a future where wildlife and people thrive again.

However, there were still significant impacts. Findings demonstrate that sensitive species and habitats are impacted by human recreational disturbance. A deeper analysis of trail use captured by the cameras showed that all wildlife tended to avoid places that were recently visited by recreational users. These include habitats such as wetlands and species groups such as lowland boreal birds and other songbirds, as well as certain mammals. And they avoided mountain bikers and motorized vehicles significantly more than they did hikers and horseback riders. Researchers found that numbers of loons and their number of years on a lake were related to the timing of recreational activity between ice out and Memorial Day and types of recreational activity such as Jet Ski, paddleboard, swimming, waterskiing, and tubing. The researchers focused on 13 species including grizzly bear, black bear, moose, mule deer, and wolf.

Increasing human presence was associated with a decreased abundance of large-bodied mammals and those with large home ranges. “We wanted to better understand the relative impacts of human recreation in this region, given its increasing popularity. We already know that motorized vehicle access can disrupt wildlife; our initial findings suggest that other types of recreation may also be having impacts,” said study author Robin Naidoo, a UBC adjunct professor at the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability.

Like many parks, the South Chilcotin Mountains provincial park and nearby regions are experiencing growing pressure from human activities — both recreational and industrial. Boreal birds were less likely to colonize sites with high rates of human visitation and more likely to become locally extinct in these locations. According to Naidoo, the study confirms that camera traps can effectively monitor both wildlife and human trail use in these and other remote regions. “We’ll be able to collect more information over time and build a solid basis for research findings that can ultimately inform public policy,” he added.

Human activities can impact wildlife through exploitation, disturbance, habitat modification, and pollution. Lack of available recreation data and challenges of modeling recreational use at unmeasured sites indicate the need for systematic monitoring of recreation visitation and additional investigations of potential impacts to wildlife. “This is the first year of our multiyear study of the region. We’ll continue to observe and to analyze so that we can better understand and mitigate the effects of these different human activities on wildlife,” said Burton. The disturbance caused by recreation pursuits or other human activities may elicit a behavioral response and physiological responses in wildlife. “Outdoor recreation and sustainable use of forest landscapes are important, but we need to balance them with the potential disruption of the ecosystem and the loss of important species.” Wildlife behavior may take the form of avoidance, habituation, or attraction.